During the 1960s, the Hmong in Laos aided the United States in the Vietnam War, providing intelligence, monitoring Communist forces that used the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos, and helping to rescue downed American airmen. When the U.S. pulled out of the war in 1975, thousands of Hmong families fled to refugee camps in Thailand. In 1976, relief agencies resettled many of these families in the United States, including Oregon. By December 1981, about 4,500 Hmong lived in the state, one of the largest such populations in the country.

Hmong refugees arrived in Portland and surrounding communities with few possessions. They spoke little English, and they were among the least educated and poorest minorities in the United States. Most brought with them only a bundle or two of clothing and household goods. At first, they relied on government assistance and, when possible, did farm work to support themselves. During harvest times, school buses took women and children to Willamette Valley farms, where they picked strawberries and cucumbers and women sold their beautiful batik, counted cross-stitch, and reverse appliqué fabrics to collectors. For the men who had worked as soldiers, finding work proved more difficult.

In the 1980s, together with other Southeast Asian refugees, the Hmong organized the Indochinese Cultural and Service Center, later named the Immigrant and Refugee Committee Organization (IRCO). IRCO and a consortium of other agencies helped the newly arrived families get oriented to American society and culture and to find jobs. As they learned English and gained job skills, Hmong men and women found work in service and production operations. Firms such as Purdy Brushes found that the Hmong men who had made their own homes, tools, weapons, and jewelry in Laos had the skills needed for producing fine, handmade paint brushes.

A downturn in the state’s economy in the early 1980s prompted many Oregon Hmong to move to California, where opportunities for jobs and services were perceived to be better. Some also moved to be closer to their extended families. By 1990, only about 600 Hmong lived in the state. The exodus was temporary, however, and by 2013 approximately 3,600 Hmong lived in Oregon, most of them in the Willamette Valley. Community health worker Jennifer Kue, who grew up in Portland, explained Oregon’s attraction to the Hmong: “Oregon reminds our elders of Laos, where the landscape is verdant and mountainous, and younger Hmong like the fact that in Oregon they are more integrated into the society at large than in states with larger Hmong communities.”

The tradition of two to three generations living together has helped the Hmong move up the socio-economic ladder. Grandparents often help raise children while parents are at work, and they sell vegetables and flowers at farmers’ markets. In 2010, the median income of Hmong households was $52,700, while the median household income for all Oregonians was $46,900. About 73 percent of Oregon Hmong who are twenty-five years or older have a high school education; about 11 percent have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Oregon Hmongs continue many traditional practices. In the late fall, Hmong New Year is celebrated, when people visit one another, young people court, and the community enjoys traditional food and music. People still use the Hmong language to communicate with their elders, although young Hmong are often not fluent. Half of Oregon Hmong now call themselves Christian. Traditionally, Hmong families who were related through a common male lineage lived together in small villages, and leadership came from the elders of each clan. Of the seventeen Hmong clans in Oregon, the Cha clan is the largest, followed by the Lee and Vang clans.

Hmong leaders in Oregon include Bruce Bliatout Thao, coeditor of Hmong National Development and a community leader; Lee Po Cha, who has been instrumental in the formation and management of IRCO and a leader of the Asian Family Center; Chia Cha, the 2014 president of Hmong American Community of Oregon, a Hmong community organization; Yer Thao, a professor at Portland State University, a pioneer print culture scholar; and Chue Blong Cha, a leader in the Cha Clan.

-

![Donated by Ruth Dowdakin. Various items of Hmong needlework acquired by donor when she worked as a volunteer ESL teacher at Sunnyside school in Portland, Oregon, in the 1970s/1980s.]()

Hmong handicraft embroidery, c.1970.

Donated by Ruth Dowdakin. Various items of Hmong needlework acquired by donor when she worked as a volunteer ESL teacher at Sunnyside school in Portland, Oregon, in the 1970s/1980s. Oregon Historical Society Museum, 2019-42.7

-

![]()

Hmong qeej. A musical reed pipe instrument made from bamboo, 1999.

Oregon Historical Society Museum, 2009-42.65

-

![]()

Hmong hat made by May and Aimee Xiong (not related). Hat is made of cross stitch and beads instead of traditional coins, 2001.

Oregon Historical Society Museum, 2009-42.21

Related Entries

-

![Chinese Americans in Oregon]()

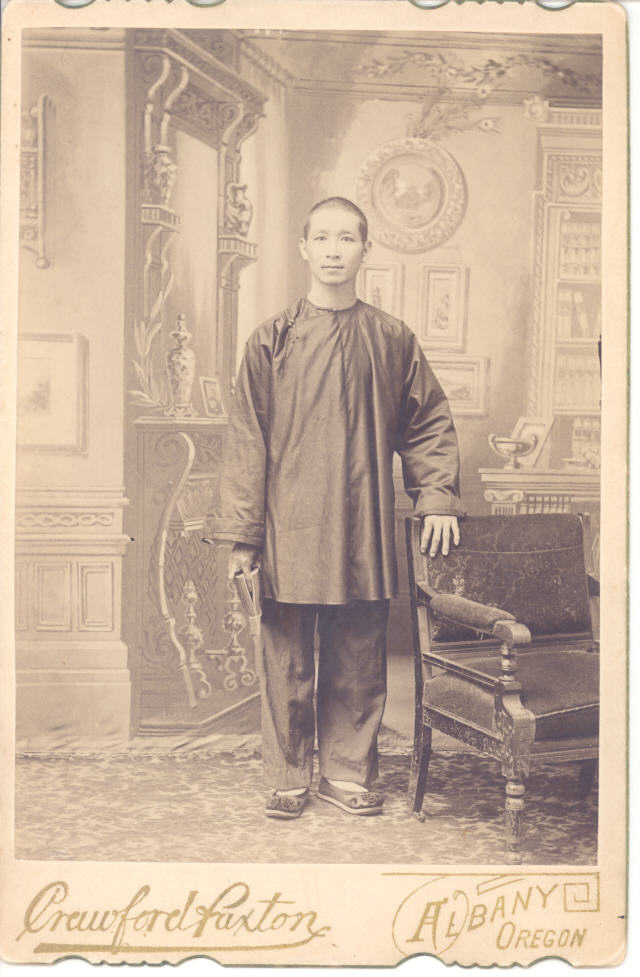

Chinese Americans in Oregon

The Pioneer Period, 1850-1860 The Cantonese-Chinese were the first Chi…

-

![Japanese Americans in Oregon]()

Japanese Americans in Oregon

Immigrants from the West Resting in the shade of the Gresham Pioneer C…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Yang, Kao Kalia. The Latehomecomer, A Hmong Family Memoir. Minneapolis, MN: Coffee House Press, 2008.

Fadiman, Anne. The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1997.

Neng Moua, Mai, ed. Bamboo Among the Oaks, Contemporary Writing by Hmong Americans. Minnesota Historical Society, 2002.

Faderman, Lillian and Ghia Xiong. I Begin My Life All Over, The Hmong and the American Immigrant Experience. Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press, 1998.

Interview with Jennifer Kue by Sami Scripter.