Few architects have influenced the State of Oregon as broadly as John Yeon. A planner, conservationist, historic preservationist, art collector, and urban activist as well as one of the state's most gifted residential designers, Yeon was a founder of the Northwest Regional Style of architecture and one of the earliest visionaries of the Columbia Gorge National Scenic Area.

The son of John Baptiste Yeon—lumber baron, construction manager of the Columbia River Highway, and developer of Portland's most elegant early high rise, the Yeon Building—John Yeon was born in 1910. At the age of sixteen, he received what he regarded as his only architectural training, as an office boy for prominent Portland architect Herman Brookman. By the time he was twenty-one, Yeon began making his mark on the state, borrowing on a life insurance policy to buy Chapman Point just south of Ecola State Park, saving what has become one of the Oregon Coast's most photographed vistas from the blight of a proposed dance hall. That same year, Governor Julius Meier appointed him to the first State Parks Commission. Three years later, the governor picked him to chair the Columbia Gorge Committee of the National Resources Board.

Yeon's 1937 Report on the Columbia Gorge is arguably the Northwest's first comprehensive environmental impact statement. It outlines the future effects of and mitigations for the future Bonneville Dam and proposes new highway standards, power rates, and public land acquisitions. In 1938, he wrote "Freeways for Oregon," proposing a series of beautification measures for roads, which the state adopted. He personally and successfully lobbied the chief of the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads to build new highways through the Columbia River Gorge and around Neahkahnie Mountain on the coast, with picturesque curves in defiance of the era's fad for geometric highway building.

Parallel to his early planning efforts, Yeon began designing houses. The first, completed in 1937 for lumberman Aubrey Watzek, would become what remains the most internationally famous house in Oregon. From the exterior, the Watzek House is a modest, somewhat austere courtyard house with flush, tongue-and-grove cedar siding. But it incorporates unprecedented technical advances: double-pane windows, hidden blinds and rain gutters, and a venting system that allows the window panes to remain fixed. Spatially, the house defied the then-burgeoning International Style's penchant for open floor plans, instead unfolding in a series of axial hallways and rooms, each a subtle study of neoclassical styles reduced to their most minimalist expressions and elegantly detailed in local woods.

A photograph of the Watzek House's austere west elevation, showing the dual roof peaks echoing the slopes of Mount Hood in the distance, was published in the Museum of Modern Art's tenth anniversary exhibit and book, Art in Our Time, in 1939 and subsequently appeared in three other MOMA exhibits and publications. Critics and curators hailed it as an important regional variant on the emerging American modernism style. In hindsight, this masterwork can be seen as something akin to the most sophisticated probings of history found in what would later be called "postmodernism."

Yeon completed designs for a dozen other residences in two genres, which he described as the "barn style" and the "palace style." They ranged from a series of speculative houses, built in the late 1930s for about $3,500 out of a new material, exterior plywood, to the dramatic Vietor house in northern California, now the headquarters for the Humboldt Area Foundation. His only public building was the Portland Visitor's Center, completed in 1947 on Portland's riverfront highway, Harbor Drive, now Tom McCall Waterfront House. Exhibited in MOMA's 1948 Built in the USA, the building still stands but as a shadow of itself, victimized by storms, neglect, and remodels.

By the mid-1950s, Yeon had shifted his focus to museum design, producing galleries for the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, the San Francisco Museum of Fine Arts, and the Portland Art Museum. He devoted increasing time to scenic conservation and ecological restoration campaigns on the Oregon Coast and in the Columbia Gorge and to architectural and parks activism in inner-city Portland.

In one of Portland's earliest public campaigns to save a historic building, Yeon enlisted the help of Ada Louise Huxtable, architecture critic for the New York Times, to successfully preserve the marble First National Bank of Oregon (now Bank of the West). He similarly fought a potentially devastating addition to Temple Beth Israel, a landmark designed by Herman Brookman. Throughout his life, Yeon worked to consolidate beachfront properties adjoining Chapman Point, stabilizing much of the beach with native grasses and trees. After his death, the sale of the property required that Chapman Point be given to Oregon Parks & Recreation for a nature preserve.

Yeon's most successful conservation efforts—and his final and most dramatic work of design—took shape in what he often described as "my Chinese landscape," the Columbia River Gorge. In 1964, he purchased a mile-long, seventy-five-acre stretch of the Columbia River's northern shore directly across from Multnomah Falls. Over the next decade, he shaped it with bulldozer, chainsaw, and plantings into what he dubbed The Shire. It is best described as an inverted English picturesque landscape in which nature instead of architecture becomes the "folly." Its wandering paths and carefully pruned foliage capture views of the falls across the Columbia, echoing the great landscape traditions of England and anticipating by a decade minimalist earthworks by artists such as Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer, and James Turrell. The Shire is now owned and operated by the University of Oregon as a center for landscape studies.

In the years before his death in 1994, Yeon continued his preservation efforts in the Gorge. His hopes that it would become a national park were never realized, but The Shire proved to be a critical recruitment tool for the preservation effort that eventually succeeded. It was during a 1980 dinner at The Shire that Yeon persuaded Nancy Russell to join him in his preservation efforts. Weeks later, she organized a picnic on Yeon's property to recruit the first members of what would become Friends of the Columbia Gorge, the most effective lobbyists in the effort to pass the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Act in 1986.

Largely self-taught and never licensed as an architect, in 1955 Yeon nevertheless became the second winner of the Arnold W. Brunner Memorial Prize for Architecture, presented by the American Academy of Arts and Letters, joining a roster that includes Gordon Bunshaft, Renzo Piano, Jean Novel, and Frank Gehry. He was made an honorary member of the American Institute of Architects in 1977.

In his Lionel H. Pries Distinguished Lecture at the University of Washington in 1986, Yeon described himself as "an environmental activist, but not of the beautifully bearded sort." As he aspired to build "a new architecture for a new landscape," his philosophy remained rooted in the picturesque or, as he put it, "a landscape painter imagining what would look good in his landscape painting."

John Yeon died in Portland on March 13, 1994.

-

![]()

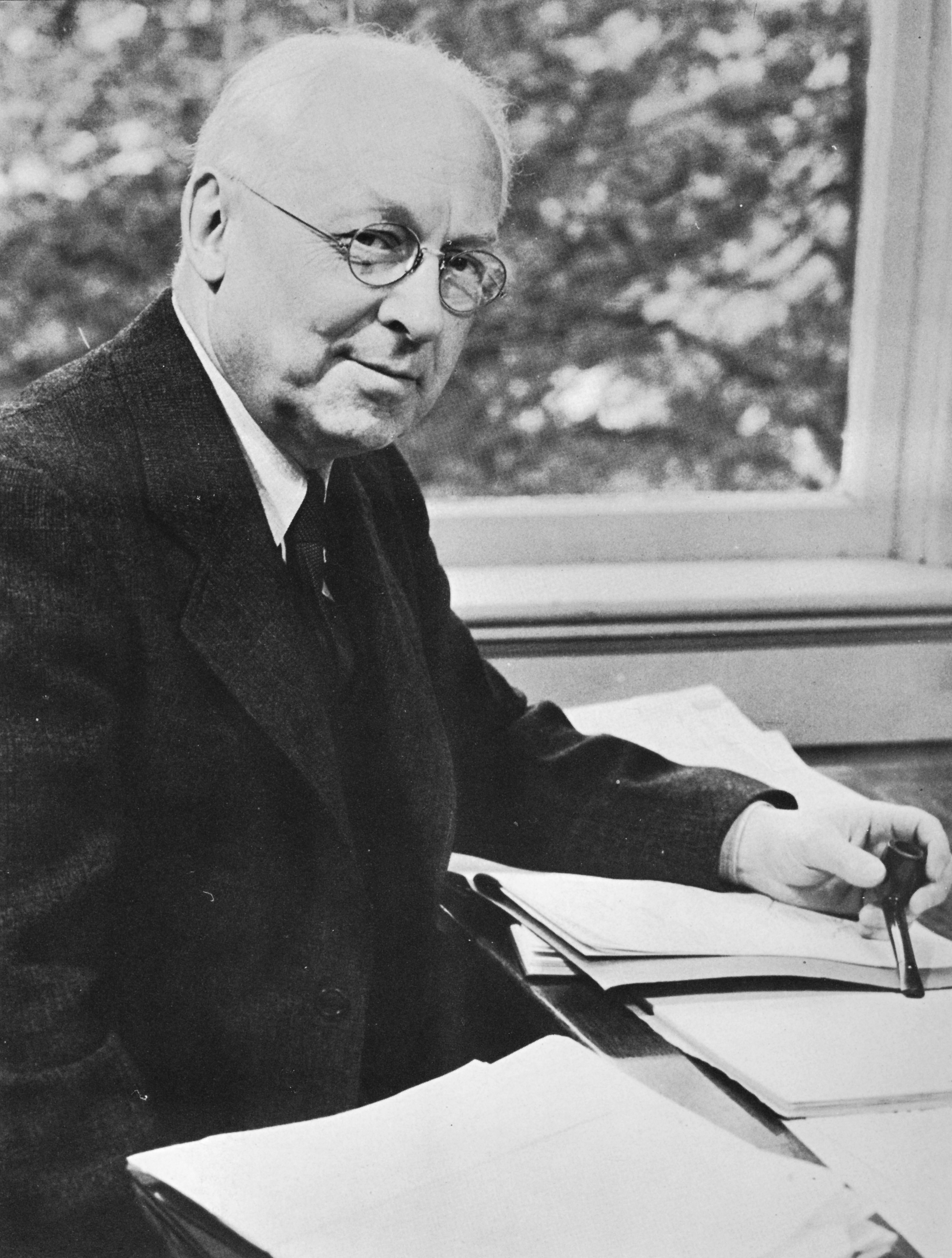

John Yeon.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library bb003003

-

![]()

Yeon's architectural drawing of the Watzek House.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Org. Lot 893, 37272

-

![Aubrey Watzek House]()

Aubrey Watzek House, 1937.

Aubrey Watzek House Courtesy UO Libraries, Building Oregon, pna_21069

-

![]()

John Yeon, 1944.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Org. Lot 893, Orhi92643

-

![]()

Yeon Building, Portland.

Courtesy University of Oregon Libraries -

![]()

Portland Art Museum, SW Park and Jefferson.

Courtesy Building Oregon, University of Oregon. "Portland Art Museum (Portland, Oregon)" Oregon Digital.

Related Entries

-

![Albert E. Doyle (1877-1928)]()

Albert E. Doyle (1877-1928)

Albert Ernest Doyle was one of Portland’s most successful early twentie…

-

![Aubrey Watzek House]()

Aubrey Watzek House

The Aubrey Watzek House (1936-1938) in Portland’s west hills could be d…

-

![Ellis F. Lawrence (1879-1946)]()

Ellis F. Lawrence (1879-1946)

Portland architect Ellis Fuller Lawrence was the leading organizer of h…

-

![Herman Brookman (1891-1973)]()

Herman Brookman (1891-1973)

With a career that spanned more than fifty years, architect Herman Broo…

-

![Pietro Belluschi (1899-1994)]()

Pietro Belluschi (1899-1994)

Pietro Belluschi of Portland was an internationally known architect and…

-

![Roscoe De Leur Hemenway (1899-1959)]()

Roscoe De Leur Hemenway (1899-1959)

Architect Roscoe De Leur Hemenway designed an estimated three hundred b…

-

![Van Evera Bailey (1903-1980)]()

Van Evera Bailey (1903-1980)

Counted among the architects who developed the Northwest Regional Style…

-

![Whidden and Lewis, architects]()

Whidden and Lewis, architects

From 1890 to 1910, the Whidden and Lewis firm dominated architectural d…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Gragg, Randy, Ed. John Yeon Architecture: Building in the Pacific Northwest. New York: Andrea Monfried Editions, 2017.

Gragg, Randy, Ed. John Yeon Landscape: Design, Conservation, Activism. New York: Andrea Monfried Editions, 2017.