Early explorers noted plankhouse structures up and down the Southern Oregon coast and at the mouth of the Coquille River. It may have been Spanish explorers Juan Perez or Bruno de Hezeta who first described them as rancherias because they reminded them of ranch outbuildings.

"At one time," U.S. Army surgeon John J. Milhau reported in November 1856, Oregon Indians were “very numerous, the number of Indian graves and the vestiges of former habitations go to show that every stream and every nook was densely populated.” By the time of American settlement, European diseases such as smallpox and measles had diminished Native populations by as much as 90 percent.

The discovery of gold in California and other western states attracted overwhelming numbers of fortune-seekers to the West. In the spring of 1853, just north of the Coquille River, gold was discovered in the beach sands of Whiskey Run Creek. Almost overnight, more than a thousand miners at neighboring Rogue River mines at Galice Creek and Gold Beach rushed to Whiskey Run. They established the town of Randolph near the village of the Nasomah Band of Coquille, in Coquille Indian territory.

The miners had little respect for the Indians or their property, and sexual attacks on Indian women became an increasing source of tension. What followed was what Indian Agent F.M. Smith described as “a most horrid massacre . . . a mass murder perpetrated upon a portion of the Nasomah.”

The Nasomah village was only a few hundred yards upriver from the Randolph Ferry (later known as Sanders Ferry), which transported miners across the Coquille River to where the Bandon Lighthouse now stands. In January 1854, several days before the massacre, a Nasomah man and the ferryman had a verbal altercation, and white men at the ferry claimed that Indians shot at them.

About forty men formed a vigilante group, the Coos County Volunteers, which included George Abbott as captain and A.F. Soap and William H. Packwood as lieutenants. On January 27, according to Agent Smith, the vigilante miners registered what he called “trivial” complaints against the Nasomah, which included riding a horse without permission, cutting the ferry rope, and refusing to meet with the Volunteers.

At dawn on the next day, the Volunteers “formed three detachments, marched upon the Indian ranches and ‘consummated a most inhuman slaughter,’ which the attackers termed a fight. The Indians were aroused from sleep to meet their deaths with but a feeble show of resistance; shot down as they were attempting to escape from their houses.” Smith reported that fifteen men and one woman were killed and that two women were wounded. Later accounts reported that twenty-one Indians died.

When he reported the massacre to Joel Palmer, superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Oregon Territory, Smith said that the miners threatened to “take his heart’s blood and give him fifty lashes, tying him to a tree and whipping him like a dog.” He resigned shortly after receiving the threat.

In response, Palmer sought to remove the Coquilles from what he called “harm’s way.” He persuaded them to sign a treaty in 1855, ceding approximately 700,000 acres of ancestral homelands.

On June 21, 1856, 710 Coquilles were transported from Port Orford to Portland by steamship and then overland to the Coast Reservation (which would become the Grand Ronde and Siletz Reservations). Some Coquilles refused to leave and went into hiding. Only those who were married to whites were allowed to stay behind.

-

![]()

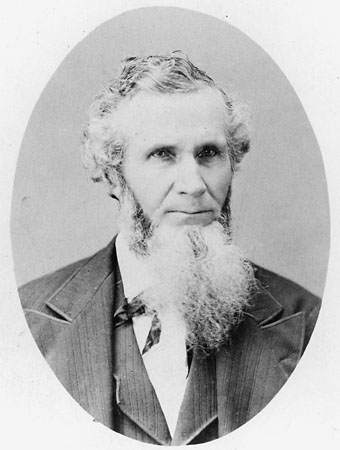

William Packwood and George Abbott.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi76068

-

![First page of Thomas Ellitson's account book, listing Coos County Volunteers. The booklet also contains supply purchases, including powder and pounds of lead.]()

List of Coos County Volunteers, 1856.

First page of Thomas Ellitson's account book, listing Coos County Volunteers. The booklet also contains supply purchases, including powder and pounds of lead. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, Mss 843

-

![Second and third pages of Thomas Ellitson's account book, listing Coos County Volunteers. The booklet also contains supply purchases, including powder and pounds of lead.]()

List of Coos County Volunteers, 1856.

Second and third pages of Thomas Ellitson's account book, listing Coos County Volunteers. The booklet also contains supply purchases, including powder and pounds of lead. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, Mss 843

-

![Site of Randolph Ferry, a few yards from the Nasomah Village.]()

Bandon Lighthouse.

Site of Randolph Ferry, a few yards from the Nasomah Village. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, photo by Wesley Andrews, bc004148

-

![View of what was once the Randolph Ferry route near the Nasomah Village.]()

Bandon Lighthouse.

View of what was once the Randolph Ferry route near the Nasomah Village. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, photo by Wesley Andrews, bc004165

-

![Aerial view of Bandon and the Coquille River, near the site of the massacre]()

Bandon and the Coquille River, 1936.

Aerial view of Bandon and the Coquille River, near the site of the massacre Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 007095

-

![Joel Palmer.]()

Palmer, Joel, OrHi27903.

Joel Palmer. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., OrHi27903

-

![A memorial for the Nasomah Massacre was built with stones from this quarry. The quarry was once a massive rock formation (Tupper Rock) sacred to the Nasomah, who called it Grandmother Rock. It was demolished to build a jetty.]()

Tupper Rock Quarry, 1918.

A memorial for the Nasomah Massacre was built with stones from this quarry. The quarry was once a massive rock formation (Tupper Rock) sacred to the Nasomah, who called it Grandmother Rock. It was demolished to build a jetty. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi104350

Related Entries

-

![Alsea Subagency of Siletz Reservation]()

Alsea Subagency of Siletz Reservation

In September 1859, Joel Palmer, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs fo…

-

![Bandon]()

Bandon

Located at the mouth of the Coquille River in Coos County, Oregon, Band…

-

Coast Indian Reservation

Beginning in 1853, Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer negotia…

-

![Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde]()

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confede…

-

![Miluk]()

Miluk

Miluk was one of two related languages spoken by people known collectiv…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Beckham, Stephen Dow. Requiem For a People: The Rogue Indians and the Frontiersman. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971.

Peterson, Emil R. and Alfred Powers. A Century of Coos and Curry: History of Southwest Oregon. Coquille, Ore.: Coos-Curry Pioneer Association, 1952.

Tveskov, Mark A. The Coos And Coquille: A Northwest Coast Historical Anthropology. Eugene: University of Oregon, Department of Anthropology, 2000.