From 1903 until about 1938, the Advocate recorded incidents of racism and discrimination in restaurants, jobs, and theaters and demanded civil rights for Oregon’s two thousand Black citizens. “Read The Advocate,” a 1925 promotional advertisement advised, “…the only News Paper in the State of Oregon that can be depended upon to fight the battles peculiar to ‘THE RACE.’” The weekly publication, which typically had four pages, also created a sense of community for Black Oregonians who were socially or physically isolated. It published birth and wedding announcements; obituaries; church, club, and cultural news; and success stories such as teens graduating from high school or men starting businesses. These snippets of daily life, typically omitted from the white press, both boosted the Black community and documented its history during the early 1900s.

The newspaper was founded by Edward D. Cannady and nine colleagues. Cannady may have worked for a Black-owned publication in St. Paul, Minnesota, before moving to Oregon and getting a job at the tony Portland Hotel as its hat-check man. Other co-creators included Edward Rutherford, a barber at the hotel; McCants Stewart, who tried to establish a law practice in the city; and John C. Logan, the hotel's head waiter.

The paper debuted on Saturday, September 5, 1903. “With this issue,” readers were informed, “The Advocate makes its initial bow to the Portland public as an independent, non-partisan, non-sectarian weekly newspaper for the intelligent discussion and authentic diffusion of matter appertaining to the colored people, especially of Portland and the State of Oregon.” Its launch may have surprised the thousand or so people in Portland’s Black community. Many had likely been reading Adolphus D. Griffin's New Age, which had aimed to keep Black Oregonians apprised of the “crucial racial issues of the day” since its founding in 1896. The two publications competed for financial support from readers and advertisers, most of whom were Black, until Griffin left Portland in 1907. The scrappy Advocate outlasted another rival, the Portland Times (1918–1923), and became the sole voice for Oregon’s Black population.

Edward Cannady said the majority of his colleagues "deserted" the Advocate within a couple of months of its debut. By 1912, the tired publisher later recalled, he was "almost tempted to give up the struggle and let the paper die." But that year he married Beatrice Morrow, a Texan who loved music, books, and entertaining, and he yielded to her most of the responsibility for running the weekly. She became the publisher after the couple divorced in 1930. Beatrice Morrow Cannady never divulged circulation figures, but she reported that the Advocate had about three thousand subscribers. Actual readership may have been closer to nine thousand due to the tendency of readers to share copies with multiple people.

Cannady said she used the newspaper to challenge sociopolitical attempts to deprive Blacks of their rights as citizens and deny them their humanity. This was apparent between 1915 and 1933, when the Advocate reported on efforts by the Portland branch of the NAACP to bar showings of the racist film Birth of a Nation. Cannady wrote about the Ku Klux Klan, which actively recruited Oregonians beginning in 1921 and staged parades and initiation ceremonies with burning crosses. She also editorialized about overt racism, including when Dr. DeNorval Unthank was unable to rent an office in downtown Portland or live with his family in a white neighborhood. She was known locally and nationally as a tenacious civil rights activist. “I must congratulate you on your fearless stand in defence [sic] of the race’s cause,” one subscriber told her, “and I hope that in all issues, in which the race is involved, that this great paper will continue to stand firm…as it has always don [sic] in the past.”

The Advocate also engaged in boosterism, an editorial strategy commonly used by frontier publishers to emphasize the positive aspects and goals of their community and to downplay negative attributes. Cannady filled the paper with notices about visiting performers such as poet Langston Hughes; local lectures by NAACP leaders, including Field Secretary William Pickens; and details about Negro History Week, established in 1926 to celebrate Black culture. The Advocate promoted a hopeful vision of Portland as welcoming, thriving, and equal even as it pointed out inequities and tried to galvanize readers to fight for equal rights. Cannady expected readers to “join the Boosters Club” and promote their city, which meant subscribing and renewing promptly, as well as patronizing the Black-owned businesses that advertised in the paper. She called those who did not live up to her expectations “knockers” and considered them a “liability.” A blunt editorial in 1924 observed that there were “entirely too many hammer throwers and too few boosters in Portland for the benefit of the progress of the race.”

The Advocate apparently folded by 1938, when Cannady moved to Southern California, but it was one of the “institutions that left a lasting legacy for Portland’s African American community,” according to the Bosco-Milligan Foundation. While impact can be difficult to measure, extant issues of the newspaper (now available in digital form as part of the Historic Oregon Newspapers collection) reveal rich conversations about interracial relations in Oregon during the early 1900s and show how the Advocate kept the realities of Jim Crow on the public agenda. Similar discussions about race and racism are evident today in the Portland Observer (1970) and the Skanner (1975), both of which strive to inform and uplift the city's African American community.

-

![]()

The Advocate, May 5, 1923.

Courtesy The Advocate

-

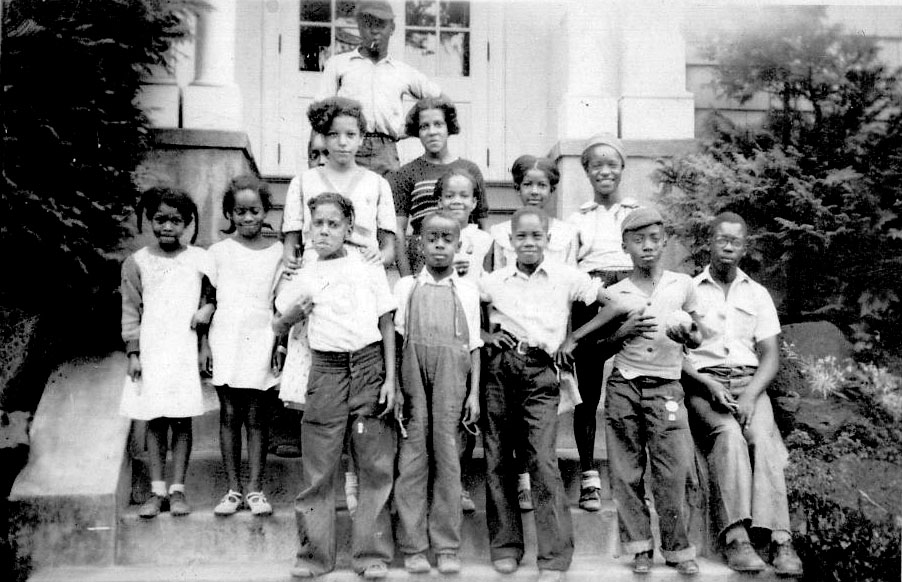

Beatrice and E.D. Cannady with son George, c. 1912.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 638501

-

![]()

The Advocate, January 31, 1931.

Courtesy The Advocate

-

![]()

The Advocate, October 11, 1930.

Courtesy The Advocate

-

![]()

The Advocate, February 14, 1931.

Courtesy The Advocate

-

![]()

"Negro History Week Begins 8," The Advocate, January 31, 1931.

Courtesy The Advocate

-

![]()

"Birth of a Nation' Harmful Picture," The Advocate, October 21, 1931.

Courtesy The Advocate

-

![]()

"'Birth of Nation' Film Again Unanimously Denied by City," The Advocate, April 11, 1931.

Courtesy The Advocate

Related Entries

-

![Beatrice Morrow Cannady (1889–1974)]()

Beatrice Morrow Cannady (1889–1974)

Beatrice Morrow Cannady was the most noted civil rights activist in ear…

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![Ku Klux Klan]()

Ku Klux Klan

Fiery crosses and marchers in Ku Klux Klan (KKK) regalia were common si…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Mangun, Kimberley. A Force for Change: Beatrice Morrow Cannady and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Oregon, 1912-1936. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2010.

Mangun, Kimberley. “‘As citizens of Portland we must protest’: Beatrice Morrow Cannady and the African American Response to D.W. Griffith’s ‘Masterpiece.’” Oregon Historical Quarterly (Fall 2006): 382-409.

Mangun, Kimberley. "Editor AD Griffin: Envisioning a New Age for Black Oregonians (1896–1907)." American Journalism 26.3 (2009): 55-92.

Oregon Experience: Beatrice Morrow Cannady. May 14, 2007; Oregon Public Broadcasting.