Sarah Winnemucca, a Paiute, had a clear purpose in life: “I mean to fight for my down-trodden race while life lasts.” Winnemucca lived part of her adult life on reservations in Oregon and was an important figure in the Bannock Indian War of 1878 before becoming a nationally prominent spokesperson for Indian justice. She is recognized for overcoming the stereotypes of her gender and race to raise public awareness of the harsh conditions that Indians endured in the United States in the late nineteenth century.

Sarah Winnemucca was born in about 1844, probably in present-day Nevada, a member of the Kuyuidika-a band that lived on the delta where the Truckee River flows into Pyramid Lake. Her Paiute name was Thocmetony, which means “shell flower.” Her grandfather Truckee and her father Winnemucca were chiefs of the band. When thousands of whites moved into the tribe’s homeland in the 1840s, attracted by claims of silver and gold on the Comstock, Truckee served as a guide for several emigrant parties.

In the spring of 1857, Thocmetony and one of her sisters lived as playmates in the home of a white settler, Major William Ormsby. The move was probably at the request of Truckee, who, according to historian Sally Zanjani, was “ever anxious for his people to learn the language and skills that would enable them to ‘get along’ in the altered world he saw before them.” While with the Ormsbys, Sarah Winnemucca later wrote, “we learned the English language very fast.”

In 1868, Sarah Winnemucca moved to Camp McDermit, a U.S. Army camp on the Nevada-Oregon state line. By 1869, she was working as an interpreter at the camp, and in 1870 she sent her first letter pleading the cause of her people. Her letter to the superintendent of Indian Affairs for Nevada was published in several newspapers, and Harper’s magazine reprinted it, bringing its author both celebrity and derision. In her autobiography, she wrote: “Those who have maligned me have not known me. It is true that my people sometimes distrust me, but that is because words have been put into my mouth which have turned out to be nothing but idle wind. Promises have been made to me in high places that have not been kept and I have had to suffer for this in the loss of my people's confidence.”

In 1875, the Indian agent at the Malheur Reservation in southeastern Oregon, Samuel Parrish, made a request that Sarah Winnemucca serve as an interpreter there, with pay of forty dollars a month. A new agent and deteriorating conditions, however, eventually impelled her to leave Malheur.

She apparently was living in John Day when people on the reservation asked her to travel to Washington, D.C., to plead their case. The Bannock War delayed her journey, however, as two hundred Bannock and Paiute warriors went to war against the United States. Like her grandfather and father, Sarah Winnemucca believed that violent resistance was fruitless, and she endured a grueling, nonstop, 233-mile horseback ride to Pyramid Lake to warn her family against joining the war. She continued to act as interpreter and guide for the army, for which some people considered her a traitor. “More than a century later,” Zanjani wrote, “some of her own people blamed her still for the deaths of those who fell in the Bannock War.”

Winnemucca believed that appeals for reform of federal Indian policy would help the Paiute. With the aid of Elizabeth Peabody, a wealthy Boston philanthropist, she undertook a lecture tour that culminated in a meeting with President Rutherford B. Hayes. Between the spring of 1883 and the summer of 1884, she gave more than three hundred lectures in the northeastern United States. She collected thousands of signatures on a petition to Congress to move the Paiute to their ancestral home in the Great Basin.

In September 1884, Winnemucca returned to Pyramid Lake, expecting a paid position as a teacher at the reservation school. When that position failed to materialize, she opened a model school for Paiute children, again with Peabody’s help. The school was never supported by government funds and probably closed in 1889.

Winnemucca was probably married three times, the last time in 1881 to Lewis H. Hopkins, an army officer she met while teaching Native children at Fort Vancouver. She died on October 16, 1891, in Montana, where she was working as a companion to a New York tourist. The cause of death is unknown, as is the site of her grave.

Her legacy is her autobiography, Life among the Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims, published in 1882, the first book written by an American Indian woman. A statue of Winnemucca stands in the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center, a gift of the State of Nevada. She was inducted into the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame in 1993, and a Reno, Nevada, elementary school is named in her honor.

-

![Sketch of Sarah Winnemucca by artist Dave Rock in 1977.]()

Sarah Winnemucca.

Sketch of Sarah Winnemucca by artist Dave Rock in 1977. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Mss 5141-23

Related Entries

-

![Camp Harney]()

Camp Harney

From 1867 to 1880, the U.S. Army’s Camp Harney provided a strategic mil…

-

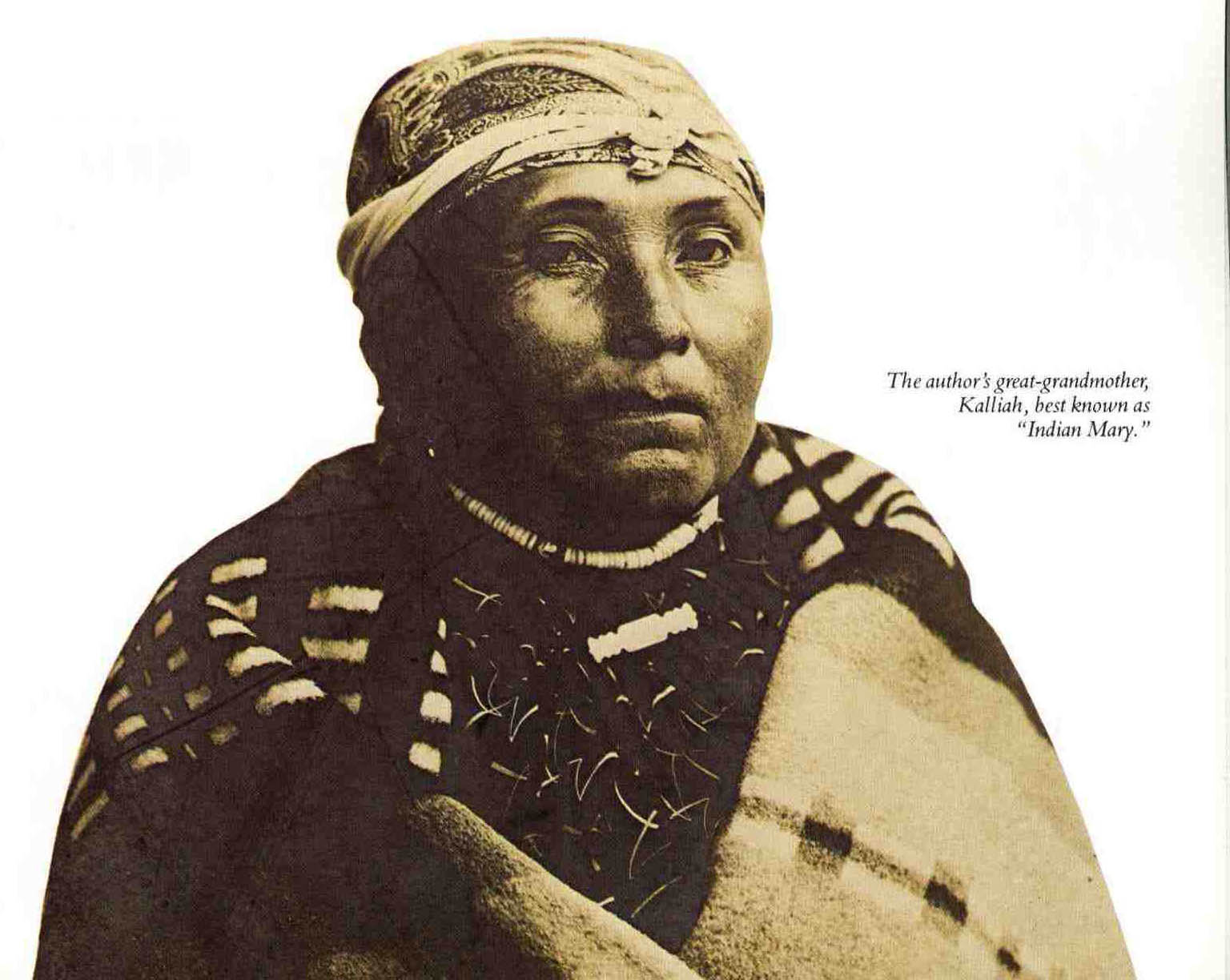

![Kalliah Tumulth (Indian Mary) (1854-1906)]()

Kalliah Tumulth (Indian Mary) (1854-1906)

Kalliah Tumulth, also called Indian Mary, was a Cascade (Watlala) Chino…

-

![Molala Kate Chantal (1844?-1938)]()

Molala Kate Chantal (1844?-1938)

Molala Kate Chantal (also known as Molala Kate)—the daughter of Molalla…

-

![Victoria (Wishikin) Wacheno Howard (c. 1865-1930)]()

Victoria (Wishikin) Wacheno Howard (c. 1865-1930)

Victoria (Wishikin) Wacheno Howard was the teller of Clackamas Chinook …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Hopkins, Sarah Winnemucca. Life Among the Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims. Boston: Cupples, Upham & Co., 1882. Available online at: http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/winnemucca/piutes/piutes.html

Ford, Victoria. "Sarah Winnemucca." Nevada Women’s History Project.

"Land of Misfortune: Sarah Winnemucca Petitions Congress." Whereas: Stories from the People's House. History, Art & Archives. United States House of Representatives. March 26, 2018.

Zanjani, Sally. Sarah Winnemucca. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2001.