A wildlife research biologist who focused on conservation during a career that spanned more than thirty years, Jack Ward Thomas specialized in wild turkeys, elk, and deer before he became embroiled in controversial political issues in the Pacific Northwest. During the 1980s and early 1990s, his work conserving old-growth ecosystems and spotted owl habitat culminated in the "spotted owl wars" and related controversies. President Bill Clinton appointed Thomas to lead the development of the Northwest Forest Plan and later persuaded him to take charge of the U.S. Forest Service. In spite of opposition from environmental groups, the timber industry, and old-guard agency personnel, Thomas was appointed the Forest Service's thirteenth chief in 1993.

Born on September 7, 1934, in Fort Worth, Texas, Thomas graduated in 1957 from Texas A&M University with a degree in wildlife management. After ten years with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, he was offered a job as a research biologist with the U.S. Forest Service at Morgantown, West Virginia. He and his wife Margaret and their two young sons moved to Morgantown in 1966. Thomas earned his master’s degree in wildlife ecology at West Virginia University and then headed a Forest Service research unit at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst. He received his doctorate in forestry there in 1972.

In 1974, Thomas was named chief research wildlife biologist and project leader at the Forestry and Range Sciences Lab in La Grande, Oregon. His tenure there began with the controversial issue of the last broad-scale application of DDT in the forest environment in the United States, battling a widespread infestation of tussock moths that were attacking Douglas-fir.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Thomas became increasingly involved in both research and politics related to the northern spotted owl, the Endangered Species Act, and old-growth forests in the Pacific Northwest. Soon after President Clinton held his Forest Summit in Portland in 1993, Jim Lyons, the USDA Undersecretary for Natural Resources and the Environment, asked Thomas to assemble a team of scientists to analyze options to protect the spotted owl while still allowing logging. The Forest Ecosystem Management and Assessment Team (FEMAT) produced a list of options on which to base the guiding principles for forest management in the Pacific Northwest. The basic underlying concept in the plan that was chosen—Option 9—was the concept of managing forest resources on the basis of ecosystem units instead of conventional administrative or political boundaries. Subsequent revisions to the plan by other agency teams ensured the plan’s failure.

In late 1993, Thomas was appointed chief of the Forest Service. After the deaths of thirty-four firefighters during the horrific fire season of 1994, Thomas instituted changes in wildland fire safety. "I gave the order and I meant it," he said. "Safety first, on every fire, every time." Years later, firefighters remembered the visits he made to fire camps that year.

When Thomas retired in December 1996, he joined the faculty of the University of Montana as professor of wildlife conservation, a position endowed by the Boone and Crockett Club, one of the nation's oldest conservation organizations. He coordinated research on the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Ranch and taught graduate students in natural resources policy, claiming he found "pontification much easier than responsibility." He retired from that position in late 2005 but remained active in conservation issues, writing, giving presentations, and consulting.

Thomas has more than 600 publications to his credit, including books, chapters, essays, and articles on elk, deer, and turkey biology; wildlife habitat; songbird ecology; northern spotted owl management; forestry; and land-use planning. He and other former Forest Service chiefs—Max Peterson, Dale Robertson, Mike Dombeck, and Dale Bosworth—have collaborated to advocate major changes in the funding of wildland fire suppression and prevention.

A book of Thomas’s journal entries during his years as chief, published in 2004, details his respect for agency employees in the field, but his assessments of political appointees and certain members of Congress are brutal. His leadership and legacy are remembered by thousands of agency employees; he told them to "tell the truth and obey the law." During his career, he taught and mentored hundreds of students and employees. "We don't just manage land," he wrote. "We're supposed to be leaders. Conservation leaders. Leaders in protecting and improving the land." Thomas passed away in May 2016.

-

![September 1997]()

Of Spotted Owls, Old Growth, and New Policies: A History since the Interagency Scientific Committee report.

September 1997 Courtesy U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station

Related Entries

-

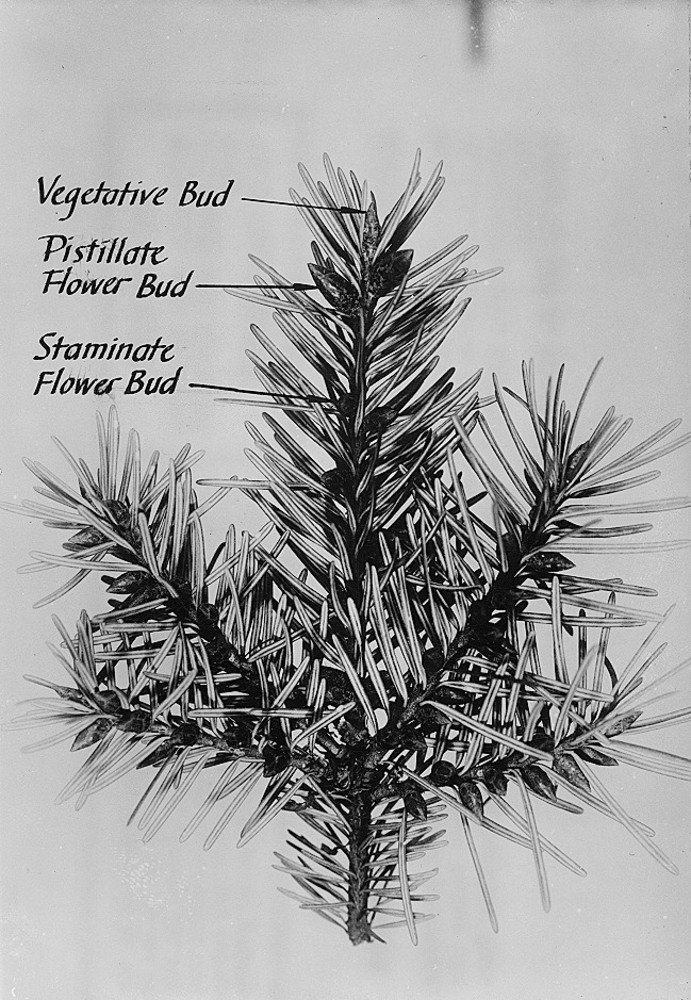

![Douglas-fir]()

Douglas-fir

Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), perhaps the most common tree in Or…

-

![Northern Spotted Owl]()

Northern Spotted Owl

Natural History The northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina),…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

"13th Chief of the Forest Service (1993-1996)." The Forest History Society. https://foresthistory.org/research-explore/us-forest-service-history/people/chiefs/jack-ward-thomas-born-1934/

Nixon, Will. "Jack Ward Thomas Goes to Washington: The Scientist Made Famous by the Spotted Owl Becomes Chief of the U.S. Forest Service -Interview." E: The Environmental Magazine (April 1994).