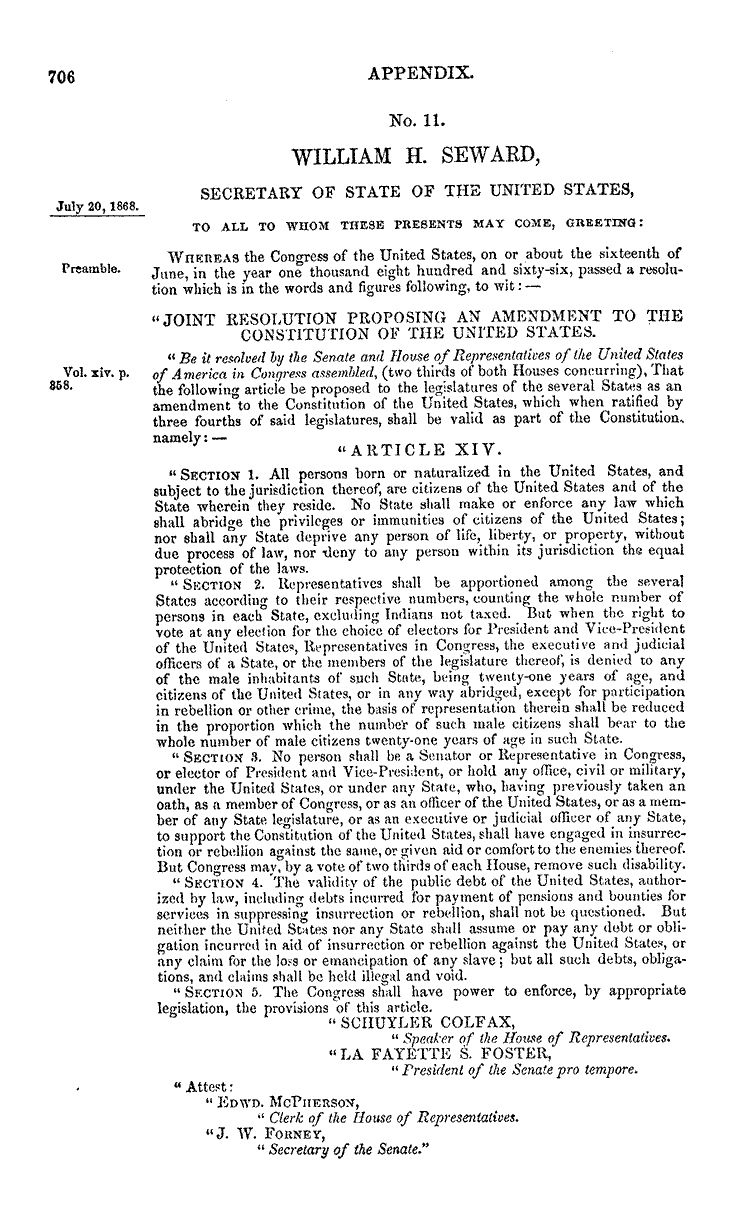

Civil War Reconstruction arguably culminated with the Fifteenth Amendment. Ratified in 1870, a year after Congress had passed it, the amendment stated that voting rights "shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." The amendment left the door open for states to discriminate on purportedly nonracial grounds, such as property ownership or literacy. But this amendment extended to African Americans a crucial right that only eight northern states had granted in 1868, just two years before.

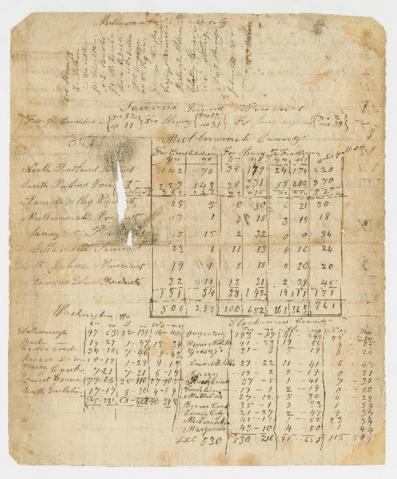

Oregon joined California as two of the five western states that considered and rejected the amendment. Oregon did not formally ratify the Fifteenth Amendment until 1959. This refusal was largely symbolic, since Oregon could not overturn the rule of the land. Hence, Oregon's Supreme Court in 1870 upheld the rights of two African American men in Wasco County to vote for county commissioner, explaining: "To hold otherwise would be to unwarrantably overthrow certain well established principles of law. . . ."

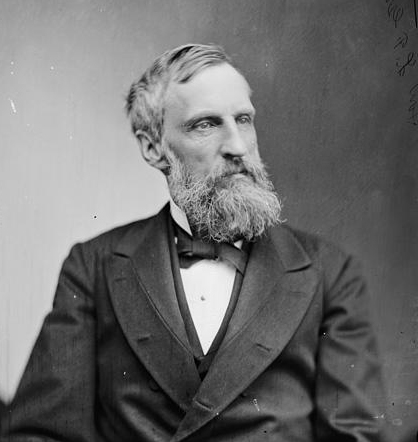

Those who opposed the Fifteenth Amendment argued that it infringed on states' rights. Governor Lafayette F. Grover, a Democrat, averred that the measure "deprived the state of the right to regulate suffrage." A Portland newspaper termed it "an odious measure" that had been forced "down the throats of the people of Oregon." The Republican Oregonian, which had five years earlier opposed granting the franchise to Blacks, observed that the "few colored men in Oregon" could have but slight political influence and that they were, in any event, generally "quiet, industrious, and intelligent citizens" who would "exercise intelligently the franchise with which they are newly invested."

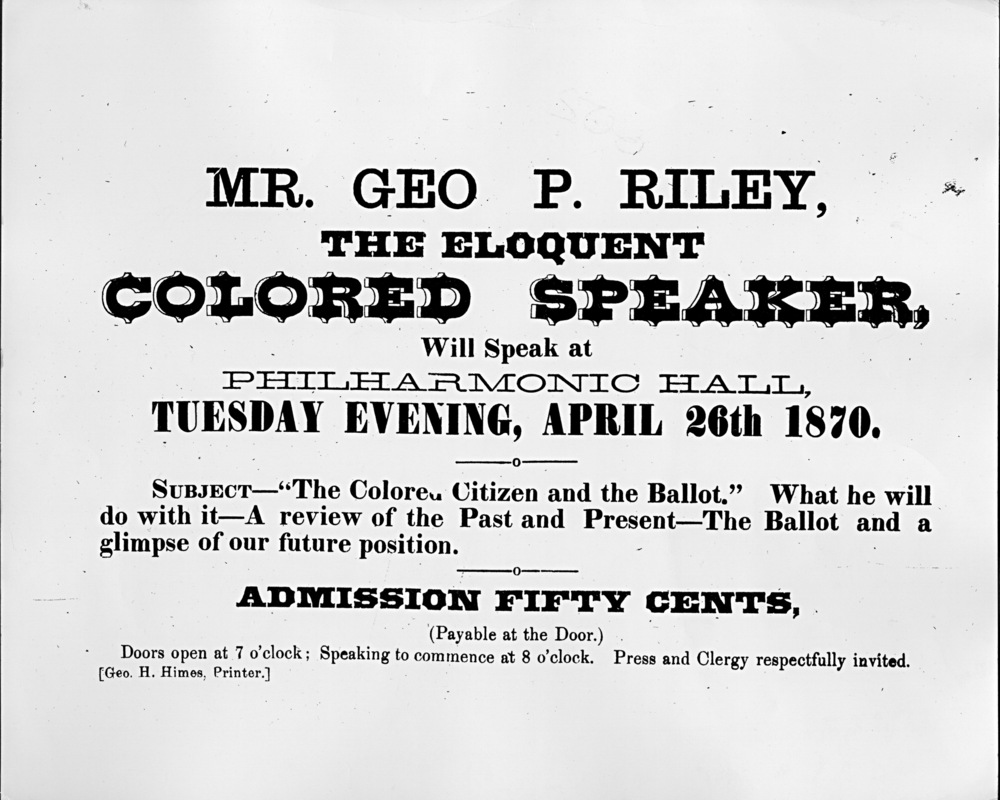

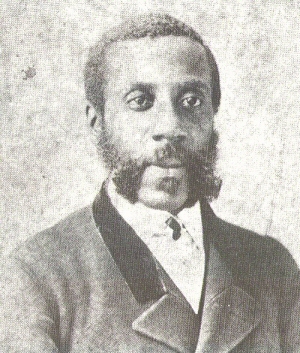

Portland's modest but growing community of African Americans certainly welcomed the Fifteenth Amendment. James Beatty, a self-employed whitewasher, headed the committee charged with planning the celebration of its passage; Edward Simmons, a bootblack, served as its secretary. The Ratification Jubilee drew many Blacks and whites and was marked by seven orators and music from the 23rd U.S. Infantry Band. All the orators, with the exception of civil rights leader George P. Riley, were white.

Portland's Black community rewarded the Republican Party for backing the amendment that enfranchised them. Riley soon spoke on the subject of "The Colored Citizen and the Ballot" and formed the Sumner Union Club—named after the prominent radical Republican, Charles Sumner. Not until the 1930s and Franklin Deleanor Roosevelt's New Deal would most African Americans in Oregon and elsewhere leave the Republican Party.

-

![Printed by George H. Himes.,]()

Poster advertising a speech by George Riley, April 1870.

Printed by George H. Himes., Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba019162

-

![Segregated soldiers were mobilized at Camp Alger during the Spanish American War]()

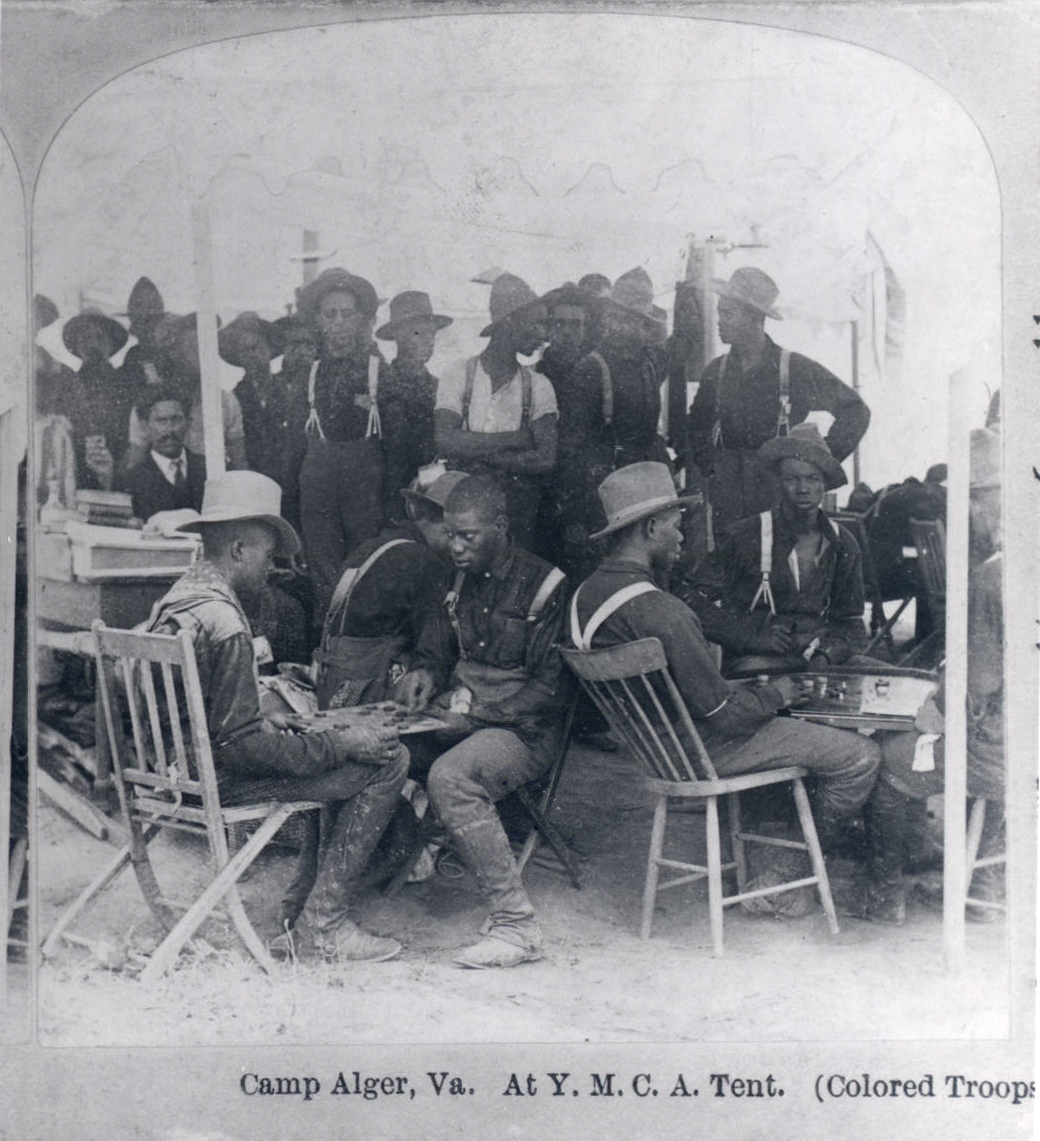

Black troops based in Virginia, c.1899.

Segregated soldiers were mobilized at Camp Alger during the Spanish American War Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 017134

Related Entries

-

![14th Amendment]()

14th Amendment

The Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution declared that the fed…

-

![Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon]()

Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon

Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws th…

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![George Putnam Riley (1833–1905)]()

George Putnam Riley (1833–1905)

Identified by the Oregonian as the “Fred[erick] Douglass of Oregon,” Ge…

-

![James William Beatty (1830–1914)]()

James William Beatty (1830–1914)

From his arrival in Oregon in about 1864 until his death in 1914, James…

-

![LaFayette Grover (1823-1911)]()

LaFayette Grover (1823-1911)

LaFayette Grover was politically one of the most successful Democrats i…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Heider, Douglas, and David Dietz, Legislative Perspectives: A 150-Year History of the Oregon Legislature from 1843 to 1993. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1995.

McLagan, Elizabeth A. Peculiar Paradise: A History of Blacks in Oregon, 1788-1940. Portland, Ore.: Georgian Press, 1980.

Richard, Keith K. "Unwelcome Settlers: Black and Mulatto Oregon Pioneers, Part II." Oregon Historical Quarterly 84 (Summer 1983): 172-205.