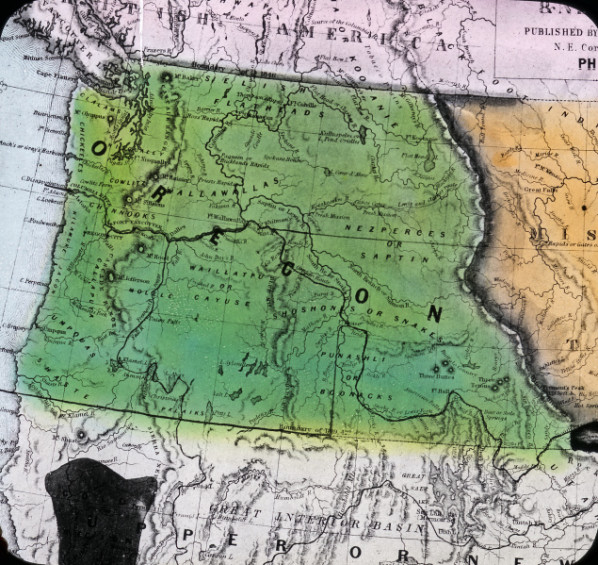

The oldest political terrestrial state boundary of Oregon—the southern state line with California—was set in 1819, four decades before statehood and without clear United States title to lands owned by Native tribes. The boundary line between Oregon and California was determined by the Adams-Onís Treaty, a diplomatic agreement between the kingdom of Spain and the United States. U.S. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and Don Luis de Onís, Spain’s minister plenipotentiary to the U.S., signed the treaty in Washington, D.C., on February 22, 1819. It was the first international agreement that legitimized an American foothold on the Pacific Ocean. The state’s two other land boundaries—the creations of Washington Territory in 1853 and Idaho Territory in 1863—were determined by U.S. political decisions.

Adams and Onís were talented foreign policy negotiators. Adams had been a diplomat since the 1790s, when his father, President John Adams, made him the nation’s representative in Prussia. In 1809, President James Madison sent John Quincy Adams to Russia as U.S. minister, and he led the American negotiations at the Treaty of Ghent in 1815, ending the War of 1812. He had long supported western expansion and was the only member of Congress from the New England states to vote in favor of the Louisiana Purchase.

Onís had taken a similar path, beginning with a diplomatic mission to Saxony in 1786 when he was twenty-four years old and subsequently holding a position as first secretary to the Spanish monarch. He spoke four languages fluently and excelled in administrative politics. Arriving in the U.S. in 1809, Onís was not officially received in Washington, D.C., until 1815 because of America’s position of neutrality with the Spanish government. While in Philadelphia, where he promoted Spain’s interests, he published several pamphlets under a pseudonym that were highly critical of the United States.

Although the negotiated goals and the results outlined in the Adams-Onís Treaty are clear and direct, its formulation was convoluted. The process had begun years before when the United States had endeavored to acquire Florida from Spain and had seized Spanish-controlled islands off the coasts of Florida and Texas. Onís knew his country could not hold Florida or acquire European allies to help defend Spain’s claims in the Western Hemisphere, but as minister plenipotentiary—a position that gave him the full support of the crown—he was not willing to surrender any more land than was necessary, especially Texas. At the same time, U.S. politicians argued that Florida had become a sanctuary for fugitive slaves who had joined with Seminole bands to ward off American authorities seeking to capture them. The only solution to the problem, the U.S. government maintained, was the acquisition of Florida.

In early 1818, the two diplomats began concerted discussions. Onís sent Adams three notes containing maps that whittled down the cession agreement of Spanish possessions in North America. Adams replied by setting the division of land on the Colorado River in Texas, northwest to longitude 105° west, then north to the forty-ninth parallel. Onís countered with a stingy release of land west of the Mississippi, along a line north at approximately longitude 93° west. In the midst of the diplomats’ discussions, President James Monroe sent Gen. Andrew Jackson to Florida to punish Seminoles for their purported raids into Georgia, a conflict that monkey-wrenched the diplomats’ negotiations and argued for a prompt completion of the treaty.

Though disposition of the Florida issue was the prime focus, Adams had a larger ambition—to persuade Spain to settle all land claims across the continent to the Pacific Ocean. With that settled, the United States would have only Britain as a likely competitor for the Oregon Country. The southern boundary of Oregon would be a byproduct of the acquisition of Florida and a single-minded desire to have legal claim to territory on the Pacific Coast.

Throughout months of negotiations, Onís continued to propose a dividing line that gave up little territory west of Louisiana. In October 1819, Adams delivered an ultimatum: the boundary of Spanish territory in western North America would be the southern bank of the Red River north to the forty-second parallel and west to the Pacific. Onís resisted but finally acceded when Adams threatened that the United States would recognize Buenos Aires as independent of Spain.

The Adams-Onís Treaty defined the “Boundary Line between the Two Countries”—Spain’s colonies and the United States—as running “West of the Mississippi,… following the course of the southern bank of the Arkansas [River]” in a northwesterly direction “to its source in Latitude, 42 North, and thence by that parallel of Latitude to the South Sea [the Pacific Ocean].” The treaty accomplished, Adams wrote in his diary, that it was “perhaps the most important day of my life….the acknowledgment of a definite line of boundary to the South Sea forms a great Epoch in our History.”

Neither diplomat in the treaty negotiations had acknowledged Native ownership of the vast western lands that were bisected in the Adams-Onís Treaty. The possession and claims to homelands of Yurok, Kurok, Modoc, Shasta, and Tolowa peoples of northern California and the Klamath, Takelma, and Chetco peoples of Oregon were considered irrelevant. The treaty had laid down an international legal line of imperial control that assumed supremacy over Indigenous people.

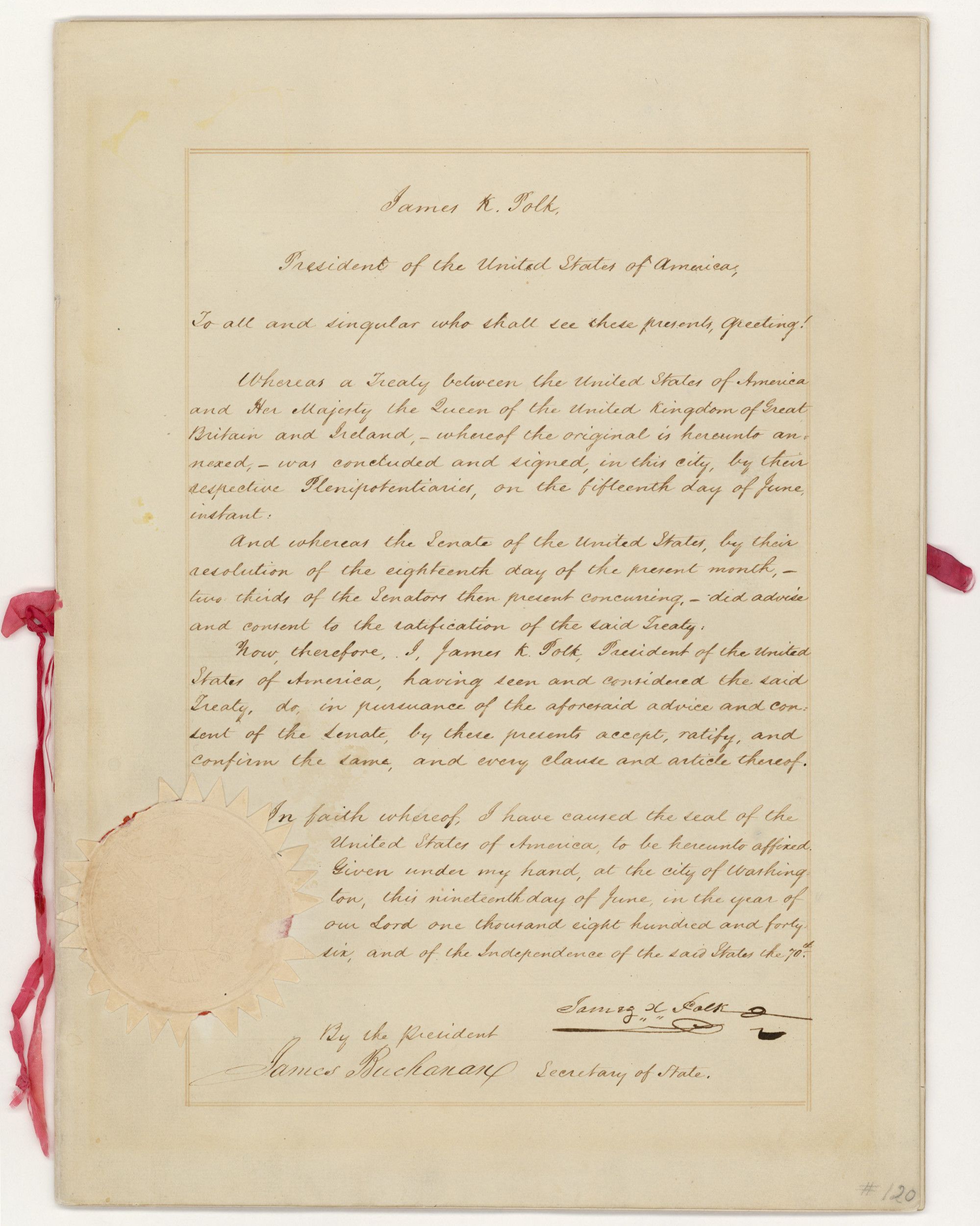

It took more than two years for the United States and Spain to ratify what was now called the Transcontinental Treaty, and Oregon Country’s southern line was officially established in 1821. Decades passed before there was any need to reify the actual location of the boundary through surveys and physical monuments. By the mid-1850s, there were sufficient disputes between Oregon Territory and California to warrant a marking of the decreed forty-second parallel specified in the Adams-Onís Treaty, if for no other reason than to clarify titles to land and, hence, the ability to tax.

The surveys and physical markings were conducted episodically over several years. Beginning east of Crescent City, California, most of the monuments, which varied from trees to piled animal bones and antlers to flint and quartz piles, were established during the 1860s. But there were uncertainties, including significant errors in the last survey in 1868. One error led to locating New Pine Creek, Oregon, a half-mile or so south of the forty-second parallel and thereby in California. The error gave Oregon from ten to twenty square miles of California land. In the mid-1980s, officials from the two states pondered pursuing a legal correction, but on reflection they recognized that the process would be costly and disruptive. They agreed to leave the anomaly alone and accept that a patch of Oregon had slid into California, a clear but acceptable violation of the Adams-Onís Treaty.

-

![]()

The Adams-Onis Treaty map.

Creative Commons Attribution -

![]()

John Quincy Adams.

Courtesy White House Historical Association

Related Entries

-

![Oregon Question]()

Oregon Question

“The Oregon boundary question,” historian Frederick Merk concluded, “wa…

-

![Oregon Treaty, 1846]()

Oregon Treaty, 1846

On November 12, 1846, the Oregon Spectator announced that Captain Natha…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Treaty of Amity, Settlement, and Limits [1819]. Library of Congress.

Barnard, Jeff. “California-Oregon Dispute: Border fight Has Town Folks on Edge.” Los Angeles Times, May 19, 1985.

Brooks, Philip Coolidge. Diplomacy and the Borderlands: The Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1939.

Foote, Francis Seeley. “The Boundary Line between California and Oregon.” California Historical Quarterly (December 1940): 368-372.

Graebner, Norman. Empire on the Pacific: A Study in American Continental Expansion. New York, NY: Ronald Press, 1955.

Landrum, Francis S. “A Major Monument: Oregon-California Boundary.” Oregon Historical Quarterly (March 1971): 4-53.

Traub, James. John Quincy Adams: Militant Spirit. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2016.

Meany, Edmond S. “Three Diplomats Prominent in the Oregon Question.” Washington Historical Quarterly (July 1914): 207-214.

Weeks, William Earl. John Quincy Adams and American Global Empire. Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.