In response to pogroms in the early 1880s, two reform-minded organizations of Russian Jews sought opportunities outside their native Russia. One group, BILU (Beir Ya'ako Leku Ve-neklja, or "Let the house of Jacob go"), chose Palestine as its destination. The other group, Am Olam (Eternal People), with its largest concentration of members in Odessa, saw the United States as the land of opportunity.

In January 1882, more than sixty Am Olamites left Odessa for New York, where they established a cooperative. Scouting parties sought locations for colonies, and one group recommended Oregon. It was one of several Russian Jewish groups seeking to form agrarian communities in the United States. Other efforts were undertaken in Louisiana, Connecticut, and North Dakota.

Influenced by the efforts of Henry Villard, who was then completing the Oregon & California Railroad between Roseburg and Ashland, Am Olam selected a site near Glendale in Douglas County. With funding from New York supporters, twenty-six Am Olam members sailed for Oregon in July 1882. Arriving in Portland in early September, a few members of the group left on foot for the site of their colony to prepare for the others, who joined them early in 1883.

The colonists called their community New Odessa, and in 1883 they adopted a constitution. One of the provisions was that colonists could not work outside the colony or engage in commerce beyond the sale of the colony's products. The constitution also specified that men and women were to enjoy equal rights. The colonists cleared land, planted crops, and furnished wood to the O&C Railroad. By 1884, the population of New Odessa had grown to sixty-five individuals.

From its inception, New Odessa faced several challenges. Most of the colonists had grown up in the city, and they found living off the land to be difficult. There were also very few women, which raised tensions among the men, most of whom were in their twenties. A constant cause of friction was the ideology of William Frey, who the colonists had chosen to lead New Odessa because of his experience with agrarian colonies in the Midwest. Frey, who was not a Jew, preached the Positivist doctrine of August Comte, and there were concerns that the colony was drifting away from its original religious views and practices.

In late 1884 or early 1885, Frey left New Odessa. Soon thereafter, a fire destroyed the colony’s main building. These events led to a rapid decline in the community, and by late 1885 only a few people remained. Some of the colonists returned to New York, where they became part of other reform movements, while others dispersed to towns in Oregon and throughout the West.

The final demise of New Odessa came in 1887, with a bankruptcy suit and foreclosure in February 1888. Although short-lived, New Odessa is noteworthy as one of the few utopian communal settlements in Oregon in the nineteenth century and especially for its links with a broader Russian Jewish communal movement in the United States.

-

![]()

Griffith Hotel, Odessa, c. 1909.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 009222

-

![]()

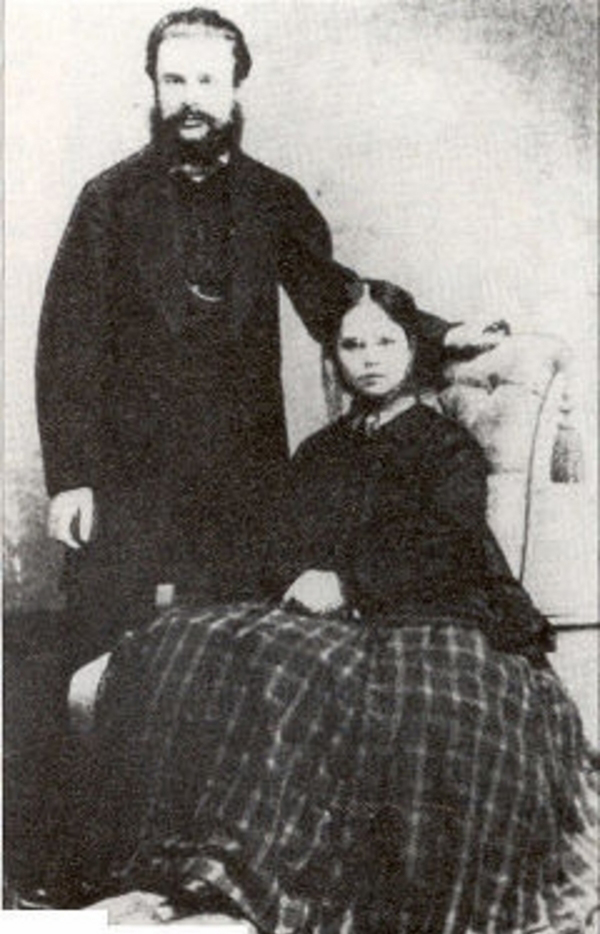

William and Mary Frey, Am Olam.

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Abdill, George B. "New Odessa: Douglas County's Russian Communal Colony." Umpqua Trapper 1 (Winter 1965): 10-14; 2 (Spring 1966): 16-21.

Blumenthal, Helen E. "New Odessa Colony of Oregon, 1882-1886." Western States Jewish Historical Quarterly 14 (July 1982): 321-22.

Herscher, Uri D. "New Odessa, Oregon." In Jewish Agricultural Utopias in America, 1880-1910 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1981), 37-48.