For over seven decades, Baker City had an area referred to as Chinatown by Chinese and whites alike. Founded in 1864, the town owed its existence to the gold rush of 1862, which brought the first settlers to eastern Oregon, including Chinese laborers and businessmen who lived in a compact area a block from the town’s main business district. Chinatown occupied two sides of Auburn Avenue for a block, bounded by Resort Street on the west and Powder River on the east.

The 1870 census counted 307 residents of Baker City, 29 of them Chinese. Ten years later, the population of Chinatown had doubled to include merchants, butchers, physicians, cooks, woodcutters, gardeners, gamblers, tailors, and prostitutes. Wesley Andrews, a local businessman, estimated that in the late 1800s Chinatown’s population swelled to several hundred during the winters, when bad weather forced miners out of mountain mining camps.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 restricted most Chinese entry into the United States. The law was a reaction to the influx of Chinese workers, especially in the West, where thousands worked for lower wages in mining, ditch digging, and railroad construction. In Baker County, a thousand Chinese dug the 125-mile-long Eldorado Ditch that delivered water to dry placer mines; and about two thousand Chinese helped build the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company line (now Union Pacific), completed through eastern Oregon in 1884.

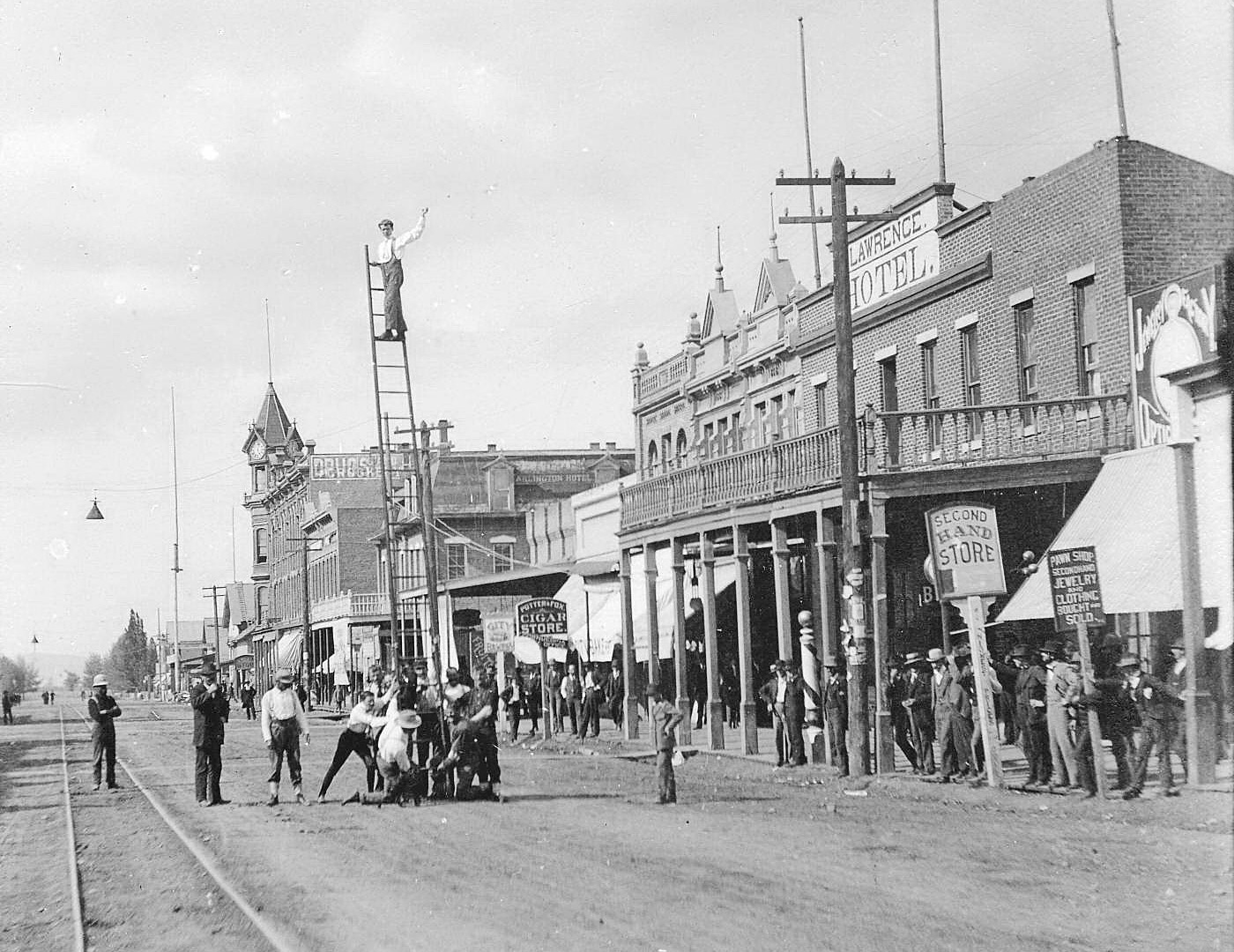

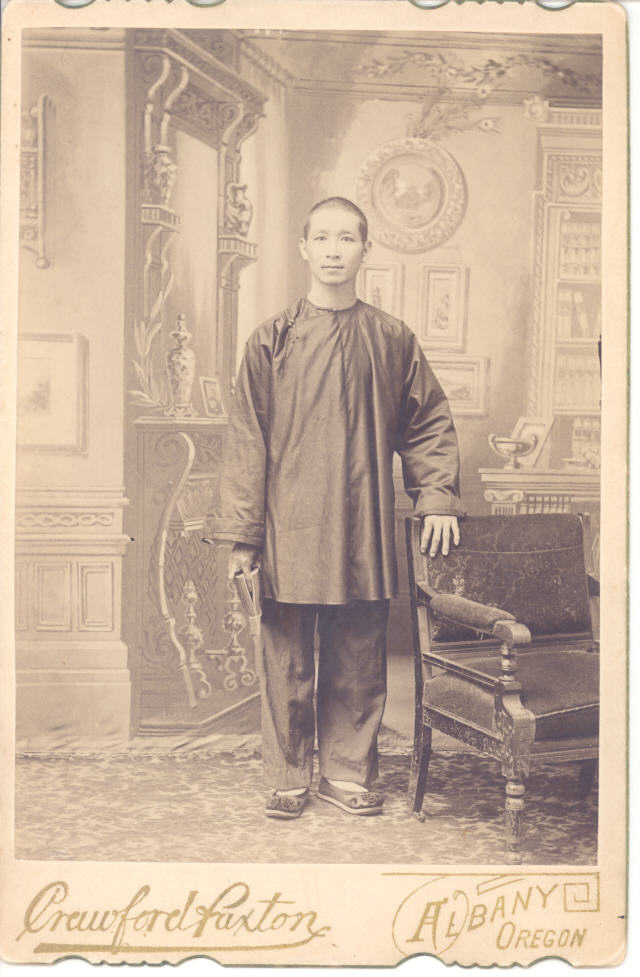

According to Sanborn fire insurance maps, there were over 50 structures in Chinatown by 1903, including 22 dwellings, 5 stores, 3 multi-story brothels, and 17 prostitute cribs, plus a brick temple housing a life-size Chinese idol on the second floor. For decades, several acres of land across Powder River from Chinatown were known as Chinese Gardens, cultivated by Chinese gardeners who sold their produce around town from baskets hung from a pole carried across their shoulders. Chinese residents also operated laundries in the downtown business district, and a number of Chinese worked in hotels and as domestics in private homes. The Chinese had their own cemetery on the northeast edge of town, from which almost all remains were eventually disinterred and returned to China.

White residents of Baker City were ambivalent about Chinese living in Baker City. Newspapers printed derogatory references to Chinese as “Celestials,” “Mongolians,” and “Yellow Horde.” In 1893, Baker City Mayor Charles Palmer said: "The Chinese quarters [need to be] thoroughly overhauled both as to sanitary and moral conditions, especially as to opium and their bawdy houses to which the youth of our town is admitted.” He considered the Chinese “a class to be pitied but one that a community cannot afford to harbor or tolerate." The November 16, 1893, Morning Democrat reported that the mayor expected Chinese residents “to conform to the same regulations as other classes.” Gambling, opium, and prostitution were illegal, but local authorities did not regulate those activities in Chinatown nearly as strictly as they did in the white parts of town.

Chinatown had its supporters. On Chinese New Year in 1906, for example, “thousands of firecrackers, quarts of Chinese gin, and pounds of candy and other Mongolian delicacies were disposed…in celebration of the last of the Chinese New Year,” the Baker City Herald reported. “A large number of Americans invaded the huts of the Celestials and evinced great interest in the antics of the yellow men.” More telling, white businessmen displayed their high regard for their Chinese colleagues returning from visits to China by vouching to emigration authorities that they had legitimate businesses in Baker City. Chinatown also had its critics. In 1906, the city built a high board gate across Auburn Avenue at the west entrance to Chinatown, walling off what was considered the shabbiest and most disreputable part of the city.

By the mid 1940s, Chinatown’s residents had gradually moved on, although the historical record does not tell us where or why they left. In the 1970s, after over a century of a Chinatown in the heart of Baker City, the last of its buildings was torn down. No physical reminder of Chinatown’s existence remains in Baker City today.

-

![Baker City with Chinatown to lower right, about 1890.]()

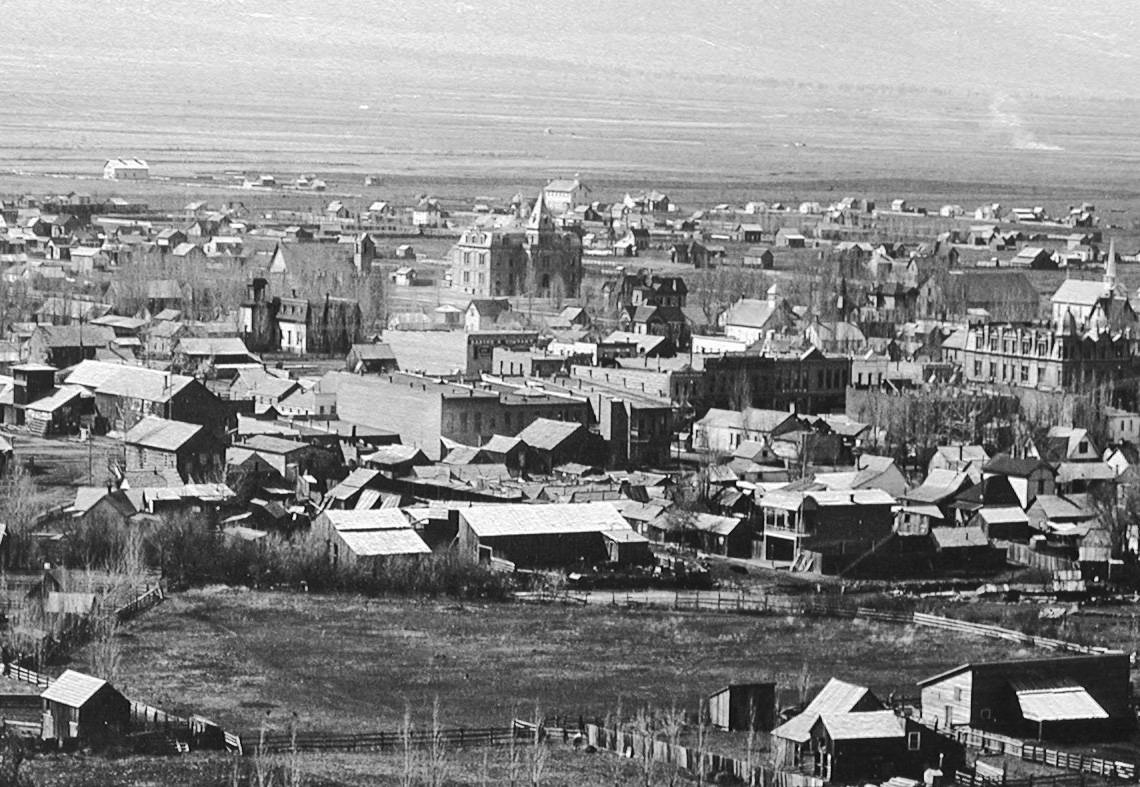

Baker City Chinatown, ca 1890.

Baker City with Chinatown to lower right, about 1890. Baker County Library historic photo collection

-

![Joss figure in Baker City's Joss House, about 1890.]()

Baker City Chinatown, Joss figure, ca 1890.

Joss figure in Baker City's Joss House, about 1890. Baker County Library historic photo collection

-

![Joss House in Baker City's Chinatown, highlighted area lower right, about 1890.]()

Baker City Chinatown, ca 1890, Joss House detail.

Joss House in Baker City's Chinatown, highlighted area lower right, about 1890. Baker County Library historic photo collection

-

![Apartments on N. side of Auburn St., Baker City, about 1925.]()

Baker City Chinatown, apt house, ca 1925.

Apartments on N. side of Auburn St., Baker City, about 1925. Baker County Library historic photo collection

Related Entries

-

![Baker City]()

Baker City

The skyline of Baker City, at an elevation of 3,440, is dominated by tw…

-

![Chinese Americans in Oregon]()

Chinese Americans in Oregon

The Pioneer Period, 1850-1860 The Cantonese-Chinese were the first Chi…

-

Eldorado Ditch

The El Dorado Ditch, also known as the Eldorado and the Big Ditch, was …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Andrews, Wesley. "Baker City in the Eighties." Oregon Historical Quarterly 50:2 (June 1949), 83-97.

Rand, Helen B. Gold, Jade and Elegance. Baker, Ore.: The Record-Courier, 1974.

Wisdom, Loy Winter. Memories: Ninety Years of Baker City. Baker, Ore.: Baker Printing & Lithography, 1976.