The career of Eleanor Baldwin, a radical journalist, reveals the cross-fertilization of reform movements in Portland during the Progressive Era. Her anti-capitalism was influenced by greenbackism, which blamed working-class poverty on powerful bankers whose manipulations of the money supply allowed them to siphon the proceeds of labor from working people. Yet, by the early 1920s, she would write in simultaneous support of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and the Ku Klux Klan in Oregon.

Born in 1854 to an abolitionist family in Naugatuck, Connecticut, Eleanor absorbed a contempt for human bondage from her father, and she would take the success of the abolition of slavery as a sign that progress could overcome the oppression faced by wage laborers. Soon after she arrived in Portland in 1905, she was hired by John Carroll, the editor of the Portland Telegram, a Republican daily, to manage the weekly woman’s page and to write a daily column for the editorial page. At the time, women’s columns were both a way for newspapers to increase female readership and a lure for department store owners, who were their biggest advertisers.

For three years, Baldwin used her column to celebrate female independence and denounce capitalists and materialism. She praised women who worked for wages, supported the development of institutions that would cater to single working women, and emphasized those women who were active in what were normally deemed male pursuits.

In 1909, Baldwin lost her column after denouncing local officials for not allowing a white woman and a Japanese man to marry. The column implied that the racist mob that had chased the couple out of California was largely Irish. Her columns had previously condemned the police for their treatment of African Americans and she had defended immigrants, including Ashkenazi Jews and Japanese, so her defense of the right of Gunjiro Aoki and Helen Gladys Emory to marry should not have been unexpected to her editors. In addition, her condemnations of capitalists increasingly took specific aim at the practices of department store managers, particularly their tendencies to underpay female employees. It is surprising that she held on to the column as long as she did.

In subsequent years, Baldwin’s efforts focused on economic themes. In 1912, she gave a suffrage speech that rejected the argument that women were uninterested in complex matters, such as tariffs. She had long implored women to study political economy and had organized a women’s economic study group. In 1915, she published a treatise on currency, Money Talks, which portrayed money as a “social force” that grew out of the collective labor of society. Money, Baldwin argued, belonged to society and, if allowed to act naturally, would enable workers to consume what they needed. What passed for money, Baldwin insisted, was merely a “transmitter” of the “money power,” and because it was controlled by bankers, its natural force was always perverted. Many of the columns she wrote for the Oregon Labor Press aimed to educate union workers that their liberation was connected to monetary reform.

Baldwin’s work blended greenbackism with New Thought spirituality, which had originated in New England and held a significant, if small, following in Portland. Lucy Mallory, the editor and lead writer of World’s Advance Thought, had blended spiritualism, populism, and New Thought into her writings since the 1880s. Gathering around Mallory was a small coterie of articulate female New Thought writers and editors that included woman suffrage advocate Clara Colby, the editor of the Woman’s Tribune, and Elizabeth Towne, who would relocate to western Massachusetts where she published the influential Nautilus. Baldwin, like the others, held that if believers concentrated their thought, then the “laws of attraction” would turn thought particles into a material force that could transform reality. A better material world would appear out of this spiritual effort. All it required was for people to think freely and to understand the importance of human-derived energies, a condition that would lead to ultimate freedom. Her treatise on money sought to further that project.

Her embrace of New Thought led Baldwin to take what appear to be antithetical positions in the aftermath of World War I. She embraced the Bolsheviks, misinterpreting them as defenders of religious liberty whose efforts would free the bodies and minds of working people, while she increasingly warned of the effort by the Catholic clergy to limit thought and thereby limit progress. In this she was hardly alone. William U’Ren, for example, who was associated with the rise of direct democracy and the single tax, concluded that the church limited free expression at the ballot; he also temporarily allied himself with Klan politics aligned against Catholic influence.

Baldwin remained active in the Women’s Press Club, among other organizations, up until her illness and death in 1928. She is buried in River View Cemetery in southwest Portland.

-

![]()

Eleanor Baldwin's daily column in Portland's Evening Telegram.

Portland Telegram, June 11, 1906

-

![In this column, Baldwin advises "bachelor" women to take an interest in other people's children.]()

Baldwin's daily column in the Portland Evening Telegram, this one dated June 11, 1906.

In this column, Baldwin advises "bachelor" women to take an interest in other people's children. Portland Telegram, June 11 1906

-

![Baldwin makes reference to her ideas about "money power" in this letter to Smith.]()

Letter from Baldwin to Eugene Smith at the Mediator, a labor publication, December 6, 1917..

Baldwin makes reference to her ideas about "money power" in this letter to Smith. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Mss 2016

-

![]()

Letter to Baldwin from Portland News editor Dana Smith on the loss of Baldwin's column, April 19, 1909.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Mss 2016

Related Entries

-

Abigail Scott Duniway (1834-1915)

Outspoken and often controversial, Abigail Scott Duniway is remembered …

-

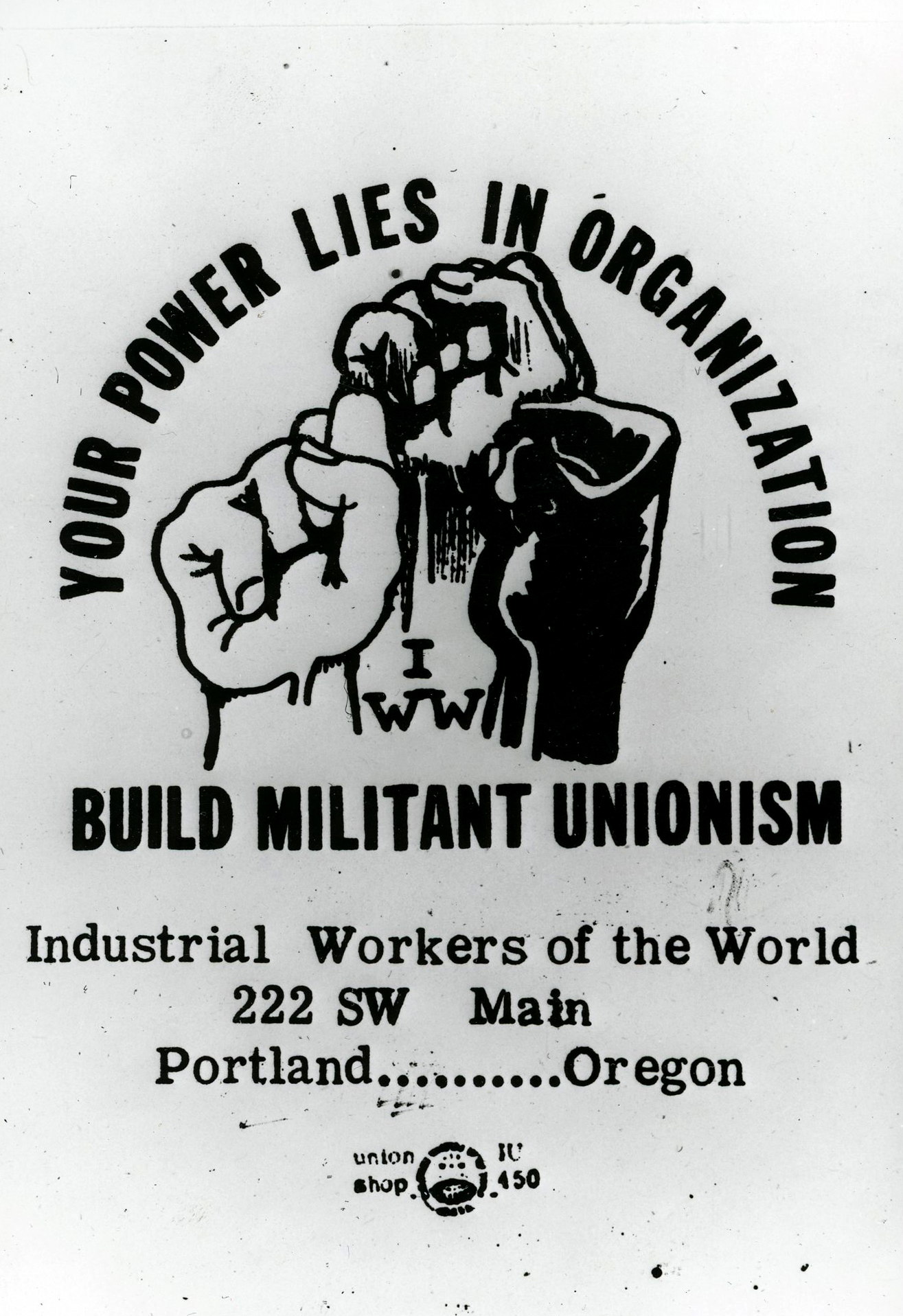

![Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)]()

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or "Wobblies"), founded in 190…

-

![Ku Klux Klan]()

Ku Klux Klan

Fiery crosses and marchers in Ku Klux Klan (KKK) regalia were common si…

-

![Marian B. Towne (1880 - 1966)]()

Marian B. Towne (1880 - 1966)

As the first woman elected to the Oregon House of Representatives (1914…

-

Marie Equi (1872-1952)

Dr. Marie Equi was a fiercely independent Oregon physician who was enga…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Lipin, Lawrence M. Eleanor Baldwin the Woman's Point of View. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2017.

Baldwin, Eleanor. Money Talks. Holyoke, Mass.: Elizabeth Towne, c. 1915.