As a newspaper editor and then as a United States senator for Missouri for three decades, Thomas Hart Benton was a champion for the American colonization of the Oregon Country during the first half of the nineteenth century.

Born in North Carolina in 1782, Benton’s family moved to a homestead in Tennessee in 1801. At age twenty-four, he opened a law practice in Nashville and was elected to the state senate. In 1815, after serving in the War of 1812, he relocated to St. Louis, where he practiced law and became acquainted with William Clark, who had been appointed governor of Missouri Territory, and fur trappers and traders, from whom he learned about the potential of the Oregon Country.

From 1818 to 1820, Benton edited the St. Louis Enquirer, which he used as a platform to advocate for Oregon occupation. He shared his concerns about the 1818 joint occupation agreement of the Oregon Country between Great Britain and the United States, because he feared losing Oregon if a treaty granting U.S. possession was not achieved. He promoted colonization of the region and reported that Oregon could support a rich economy of “furs and bread.” His vision included a trading connection that would benefit St. Louis.

Benton was elected by the General Assembly to serve as one of Missouri's first two U.S. senators in 1820 (Missouri had been admitted to the Union as a slave state as part of the 1820 Missouri Compromise; its statehood was ratified on August 10, 1821). He wasted no time speaking in favor of a bill during a session in January 1821 to “authorize the occupation of the Columbia River and to regulate trade and intercourse with the Indian tribes therein.” While the bill drew little support, “the first blow was struck,” Benton later wrote in his memoirs.

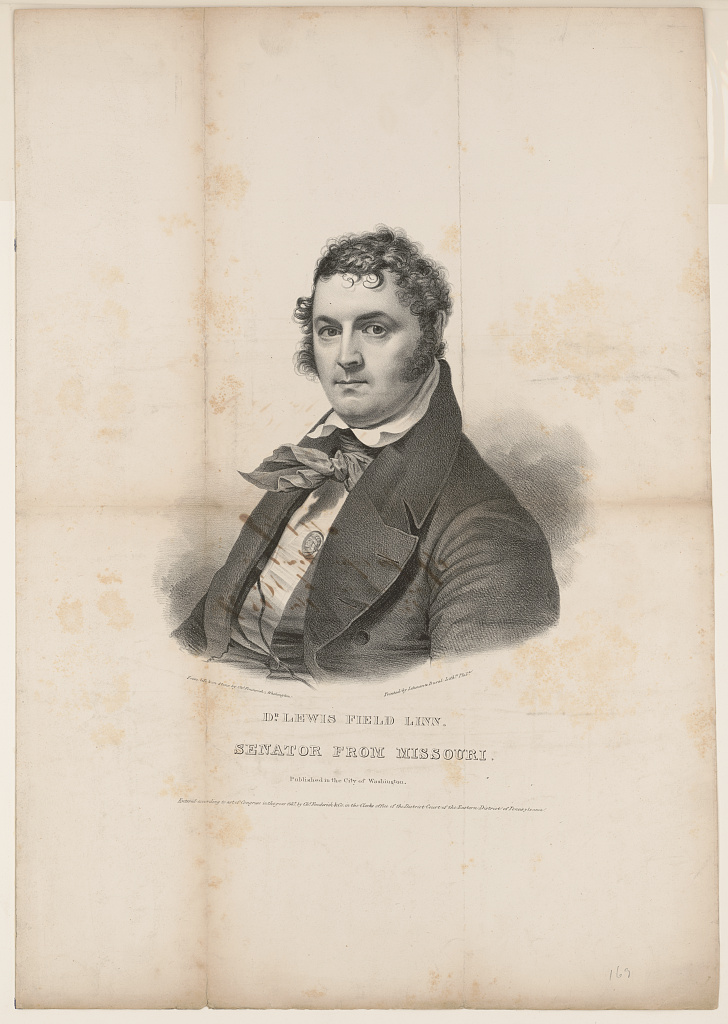

The Oregon Question, as it came to be known, was debated often in the Senate, with Benton as one of Oregon’s strongest supporters. In 1833, he acquired an important ally, Missouri Senator Lewis Linn, and the two men worked closely together to advance proposals for federal involvement in the Oregon Country. A bill introduced by Linn shortly before his death in 1843 would have established forts from St. Louis to the mouth of the Columbia, provided land grants, and extended legal jurisdiction from Iowa Territory to the Pacific. The bill passed the Senate but failed in the House.

In 1842, Benton promoted a U.S. Army expedition led by his son-in-law, Lieutenant John C. Frémont, to map the Oregon Trail from Missouri to South Pass in present-day Wyoming. Frémont and his wife, Jessie Benton, collaborated on a report of the expedition that achieved wide readership and stimulated considerable interest in Oregon resettlement.

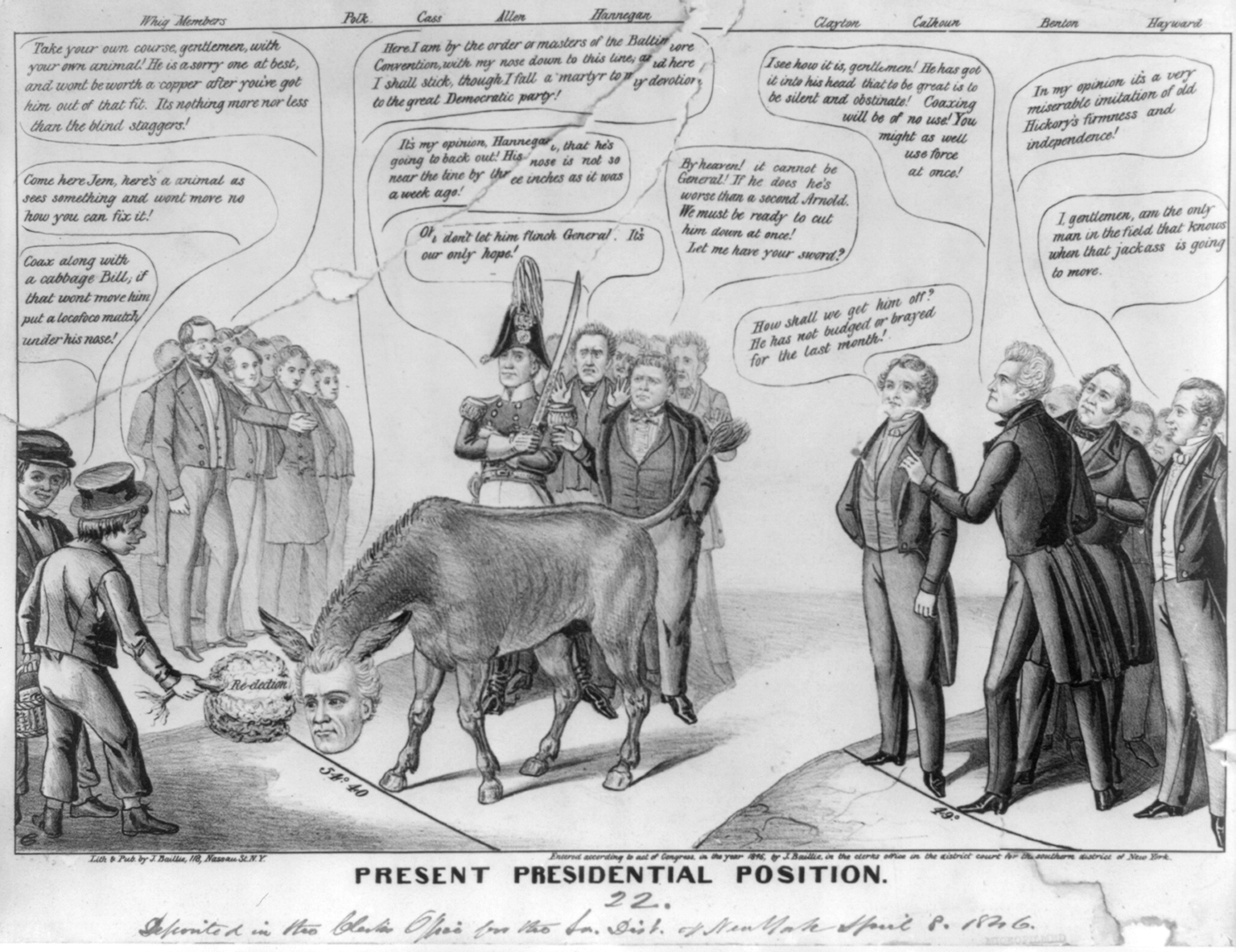

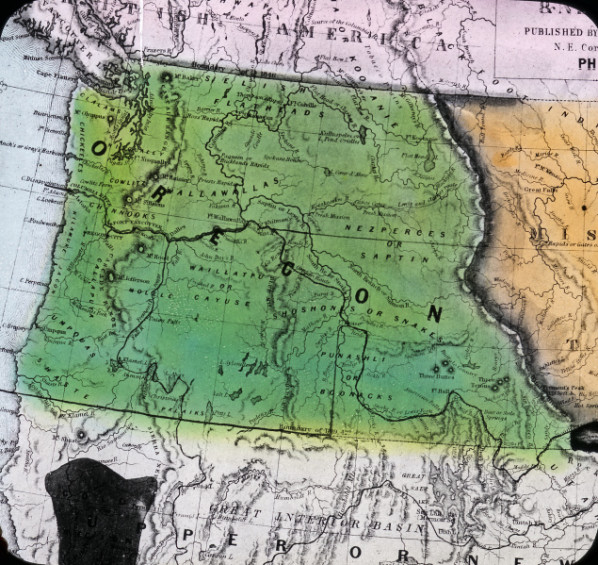

By 1844, more than 2,600 people had emigrated to the Oregon Country, and the time had come, Benton judged, for action that he had advocated for decades. James K. Polk’s expansionist platform in the 1844 presidential campaign focused prominently on Oregon for inclusion in the American republic. Although some expansionists demanded that the United States take possession of the entire Oregon Country by force of arms against the British if necessary—the “54-40 or Fight” threat, which referred to the area's northern-most boundary line—Benton had long favored the 49th parallel as a more reasonable boundary. He worked closely with President Polk on negotiations with the British and in June 1846 successfully led the Senate debate that gained approval for the Oregon Treaty. The treaty ended joint occupation with Britain and gave the U.S. possession of the Oregon Country to the 49th parallel, which marks today's U.S./Canada border.

Benton also led the effort to pass a bill establishing Oregon as a U.S. territory in 1848. From the start, the proposal was caught up in the slavery issue. The Oregon Provisional Government had outlawed slavery but had also passed exclusion laws, blocking the residency of free Blacks. Though Benton was a Southerner and a slave owner from a slave state, he was also a Free Soiler who worked against the expansion of slavery to “protect” free white labor in the West, and he did so in the case of Oregon. His frustration spilled over in debate: “We can see nothing, touch nothing, have no measures proposed, without having this pestilence [slavery] thrust before us.” Only hours before the close of the 30th Congress, Benton’s motion to pass the House version of the bill that left standing the exclusion of slavery in Oregon succeeded by a vote of 29 to 20. He was one of only two Southern senators who voted for the bill.

In 1851, Benton's controversial positions on the Oregon Country's northern boundary and on the extension of slavery to the new territory likely contributed to his being replaced after thirty years in the Senate. He died seven years later, on April 10, 1858. Benton County, named for Benton in 1847 by the Oregon Provisional Legislature, honors a man who, at crucial times, was a persuasive advocate for the Oregon Territory.

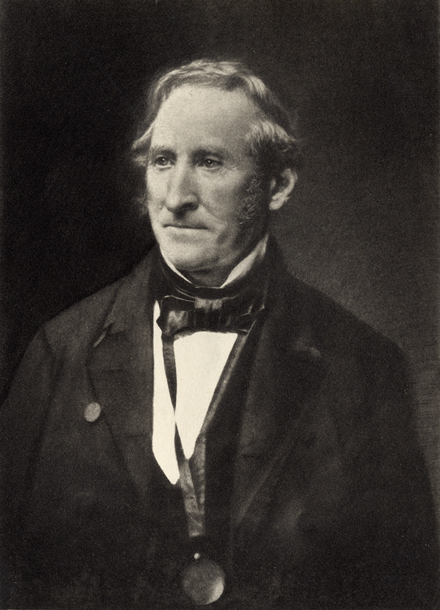

-

![]()

Thomas Hart Benton.

Courtesy U.S. Senate -

![A political cartoon illustrating the debate over the Oregon Question: briefly, Pres. Polk stubbornly clings to the 54'40" boundary line for Oregon Country, risking war with Great Britain over region that had been jointly occupied by the two countries. Benton is shown to the right advocating for the 49th parallel (today's border with Canada).]()

Related Entries

-

![Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon]()

Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon

Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws th…

-

![John Floyd (1783–1837)]()

John Floyd (1783–1837)

During his service in the U.S. House of Representatives, John Floyd of …

-

![Lewis F. Linn and Oregon]()

Lewis F. Linn and Oregon

Senator Lewis F. Linn of Missouri was a tireless advocate for the Unite…

-

![Oregon Question]()

Oregon Question

“The Oregon boundary question,” historian Frederick Merk concluded, “wa…

-

![Provisional Government]()

Provisional Government

The Provisional Government, created in May-July 1843, was the first gov…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Hansen, William A. “Thomas Hart Benton and the Oregon Question.” Missouri Historical Review 63 (July 1969): 492.

Shippee, Lester Burrell. “The Federal Relations of Oregon—III.” Quarterly Journal of the Oregon Historical Society 19 (December 1918): 283–333.

Smith, Elbert B. Magnificent Missourian: The Life of Thomas Hart Benton. New York: J. B. Lippincott, 1958.