On July 13, 2002, a series of electrical storms passed over southwestern Oregon's Siskiyou Mountains. That afternoon's barrage of lightning strikes ignited five separate fires within the vast Kalmiopsis Wilderness. By early August the fires had grown together into a single, massive, and expanding conflagration that burned well into October. The U.S. Forest Service dubbed it the Biscuit Fire.

With a burned area totaling just forty acres shy of a half-million acres, the Biscuit Fire is believed to be Oregon's largest forest fire of record. The efforts of the Forest Service to control the fire kept the attention of the American public throughout the summer and fall of 2002.

Much of the burn was located inside the wilderness, where the Forest Service's fire-fighting effort was purposely limited in its methods and extent. Nevertheless, a nearly unprecedented amount of over $150 million was spent on containing and suppressing the fire, especially after it jumped the Illinois River and expanded outside the wilderness to threaten commercial forestland and other resources and homes. The fire-fighting effort involved setting large backfires, and the immense smoke columns rising from some of the controlled burns badly frightened some residents of the Illinois Valley.

During the first week of July 2002, just before the fire erupted, suppression of forest and range fires burning elsewhere in the West already had employed most of the nation's available fire-fighting assets, including smokejumpers, ground crews, helicopters, fixed-wing retardant air tankers, heavy equipment, and logistical/overhead teams. With the bulk of the nation's fire-fighting forces engaged elsewhere, the fires that had started in the Kalmiopsis were not subject to suppression efforts, except from small ground crews, for several more weeks. Some disagreement exists over whether or not the Forest Service requested any smoke-jumper crews during the first days of the then-small wilderness fires (something that, in addition to the ground crews, might have kept the fires from growing larger); recently recovered available records do indicate that some smoke jumpers and other fire-fighting resources were available to be dispatched to what became the Biscuit Fire, but were not sent..

The first of the five fires spotted at 3:17 p.m. on July 13 consumed no more than an acre of brush, but by August 1 the Biscuit Fire had extended into California. In early August, equipment and weary crews arrived to tackle the fire. The work force of over 7,000 people—who operated out of three main fire camps near Cave Junction, Brookings, and Gold Beach—included firefighters from Mexico and technical personnel from Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

The Biscuit Fire was not declared fully "controlled" until well into November, and it continued to burn within the containment perimeter until the winter rains. The Forest Service declared it officially extinguished on December 31. The fire had burned a historic fire lookout and fewer than a dozen buildings, largely cabins on mining claims or on small parcels of private land in the Kalmiopsis. No lives were lost due to the fire or to the suppression effort.

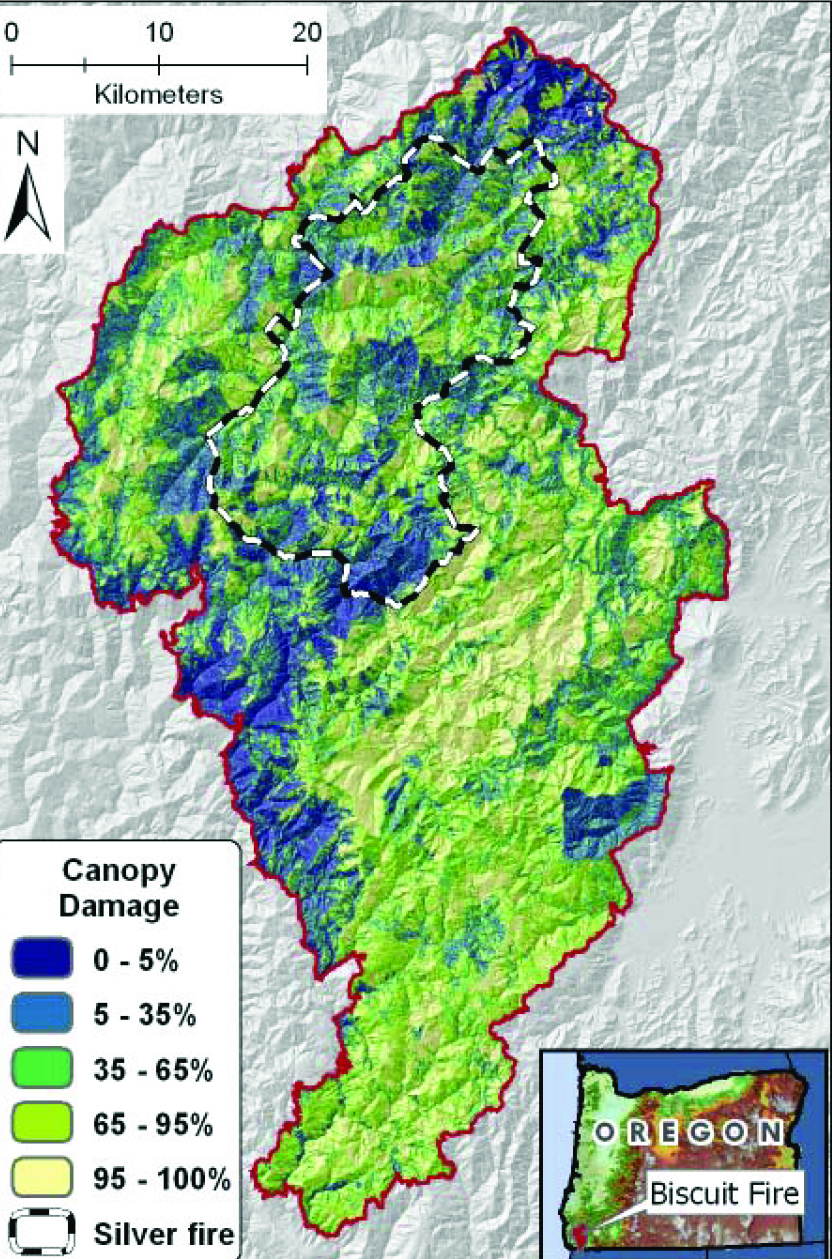

Much of the Biscuit Fire "burned cool," leaving substantial vegetation unconsumed. Only about half the area burned hot enough to kill at least 75 percent of the trees and shrubs.

The forests of the Kalmiopsis Wilderness have historically been fire-dependent—that is, requiring frequent low-intensity fires to clear out undergrowth so that widely scattered trees can thrive. One factor in the reports of timber mortality from the Biscuit Fire likely was partly the result of decades of fire-suppression: by 2002, many of the brush fields consisted of what the Forest Service described as "decadent, old-growth" manzanita and tanoak, with plenty of dead branches remaining near ground level. Those burned far more severely than in times past, causing the fire to crown into the tall pines and firs.

In the years immediately after the Biscuit Fire, the Forest Service proposed to salvage-log some sixty-seven million board feet of the fire-killed timber outside the wilderness area. The proposal, which involved less than one percent of the total area burned, led to legal battles and attempts by protesters to block logging trucks. The courts consistently ruled for the Forest Service and, despite requiring federal and local law enforcement officers to keep the roads open, the salvage logging proceeded.

-

![]()

Map of Biscuit Fire boundaries, 2002.

Courtesy USGS, Tom Spies -

![Siskiyou National Forest]()

Siskiyou National Forest.

Siskiyou National Forest Courtesy United States Forest Service

Related Entries

-

![Forest Fires of 1910]()

Forest Fires of 1910

During the late summer of 1910, a searing drought combined with high-ve…

-

![Indian Use of Fire in Early Oregon]()

Indian Use of Fire in Early Oregon

Anthropogenic (human-caused) fire was a major component of the Native s…

-

![Kalmiopsis Wilderness]()

Kalmiopsis Wilderness

The 179,850-acre Kalmiopsis Wilderness, located in southwestern Oregon …

-

![Oxbow Ridge Fire of 1966]()

Oxbow Ridge Fire of 1966

Oregon’s forests were extremely dry in August 1966. Hot east winds bega…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

U. S. Government Accounting Office. "Biscuit Fire: An Analysis of Fire Response, Resource Availability, and Personnel Certification Standards" (GAO-04-426). April 12, 2004. http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-04-426.