The history of African American cowboys in Oregon begins well past the state’s frontier era. There were almost no Black cowboys in Oregon during the nineteenth century and only a few during the twentieth century, when cowboys became entertainment figures. Nevertheless, the existence of Black cowboys in Oregon provides an important reminder that cowboy culture in the state had some diversity. It is also significant that so few Black cowboys lived and worked in the state until after the traditional role of the cowboy had changed, in stark contrast to other frontier states, where Black people played important roles in settling the land and participating in rodeos.

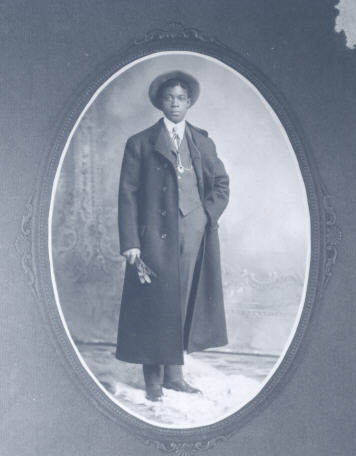

Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, the growth of Oregon’s Black population was limited by local and statewide exclusionary policies and a reluctance to grant racial minorities civil rights. As a result, there were barely more than a thousand Black people in the state. Even smaller was the number of African Americans who lived in rural areas. In 1870, 44 percent of the Black population lived in Portland; by 1900, that number had reached 70 percent. The isolation of rural Oregon, where sentiments against Black people were strongest, could be dangerous, and the few Black people who lived outside cities mostly worked as tradesmen or as servants to white families. As a result, very few African Americans worked as cowboys in nineteenth-century Oregon. One exception was Joseph Sewell, who lived in the Pendleton area. A talented horsemen and a better fighter, Sewell died in 1890 in a brawl.

The transformation of the cowboy to a figure of entertainment at the turn of the twentieth century opened up new opportunities for African Americans to participate in commercial horse racing, bull riding, wrangling, and bucking. While Black cowboys were still subject to racist treatment—including being expected to play a racial stereotype as a part of their act and being judged unfairly alongside white competitors—they also had opportunities to demonstrate their skill on horseback.

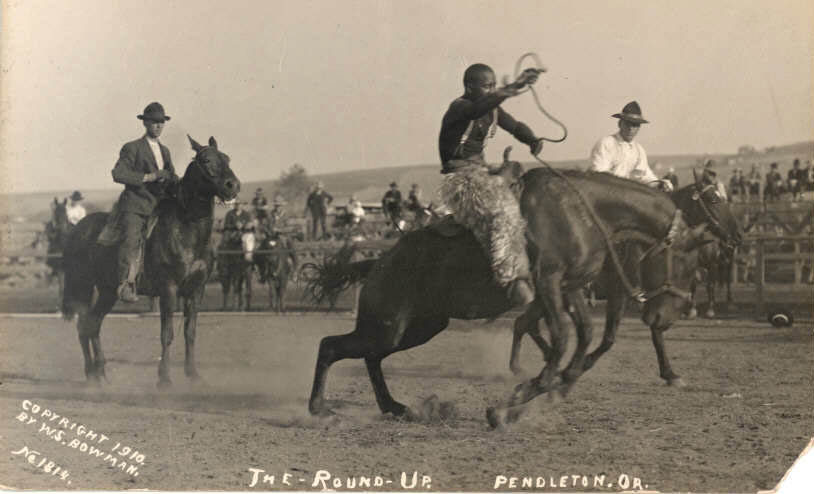

Oregon’s most celebrated rodeo, the Pendleton Round-Up, began in 1910 and included African American competitors from the beginning. The Round-Up’s most famous Black rider, George Fletcher, was born in the Midwest, but he moved to Pendleton as a young man, learning from horsemen on the nearby Umatilla Indian Reservation. Throughout the 1910s, he enthralled audiences with his flamboyant style, which included wearing bright orange chaps, and his loose, relaxed way of riding that made every movement look as though it would fling him off.

In 1911, Fletcher competed against John Spain, who was white, and Jackson Sundown, who was Nez Perce, in the bucking finals. Spain was awarded first prize, but the crowd disagreed with the judge’s decision and cheered loudest for Fletcher. Most spectators agreed that Fletcher had ridden better and that the decision derived from the judge’s reluctance to award the first prize to a nonwhite man. Fletcher would later serve in the military during World War I, where he sustained injuries that ended his rodeo career.

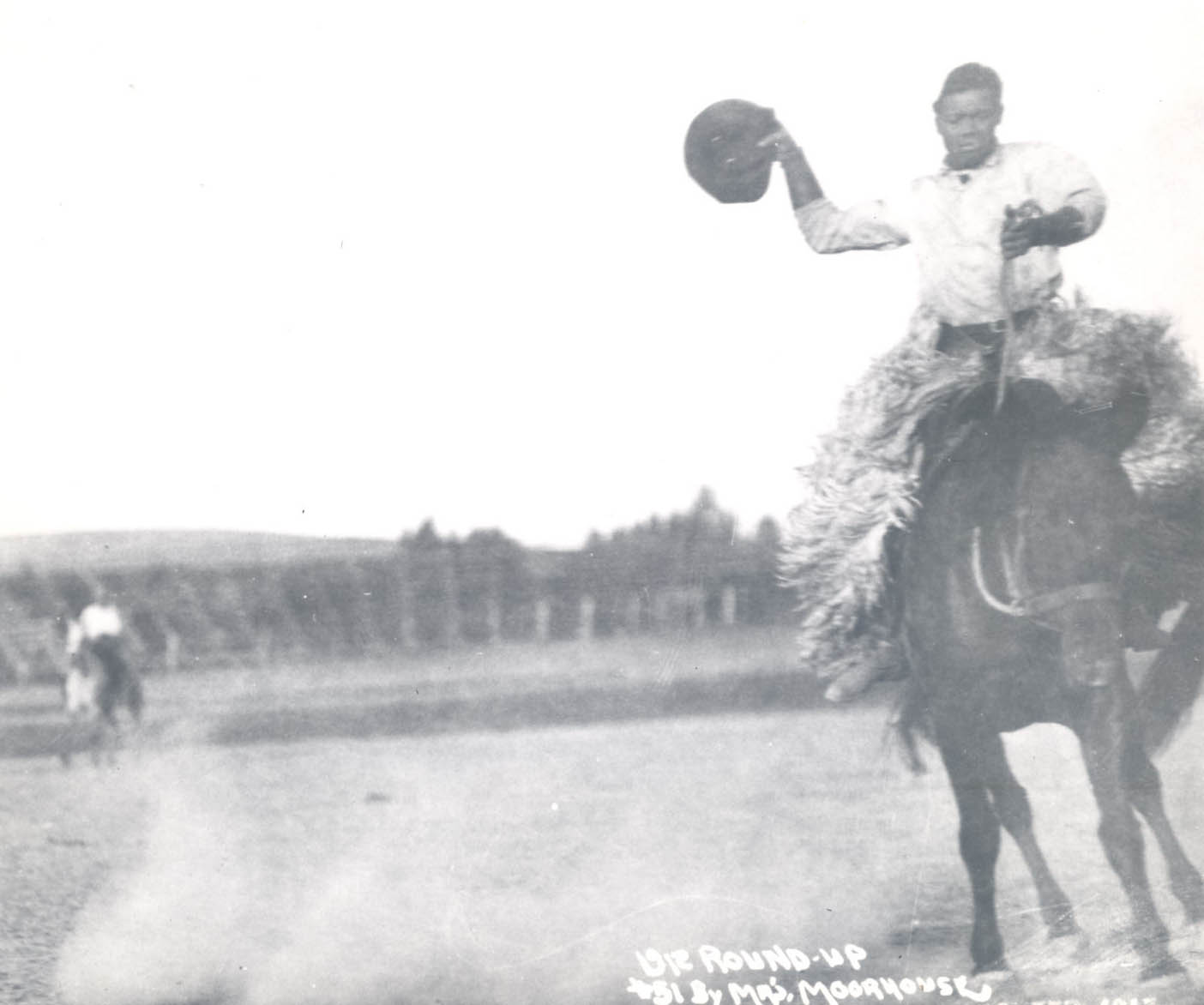

Several other African Americans also competed in the Round-Up during the 1910s. Jesse Stahl, a professional cowboy widely considered to have set the standard for bronco-riding, was already famous by the time he competed in the Round-Up in 1912. His performance in the Salinas Rodeo in California that year as well as his invention of “hoolihanding,” a dangerous maneuver that involved jumping from a horse to a bull before wrestling it to the ground, made him an important attraction at the Round-Up in the four years he competed, from 1912 through 1916.

The 1910s proved to be a short-lived era for diversity in the Round-Up. As time passed, rodeo’s cultural association with the image of the white male cowboy grew stronger. Alongside the resurgence of anti-Black racism in Oregon during the 1920s and the increasing urbanization of the Black population, there was a sharp decline in the number of Black rodeo competitors.

The number of Black cowboys competing nationally increased in the late twentieth century, supported in part by the formation in 1984 of the Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo, an all-Black touring company. The rodeo is named for Bill Pickett, a Black bulldogger who gained national fame in Hollywood cowboy films; he competed at the Pendleton Round-up in 1915. Recent Pendleton Round-Ups better reflect the growing diversity in rodeo competions. In 2023, Texan Fred Whitfield was inducted into the Pendleton Round-Up Hall of Fame in recognition of his three Pendleton Championship wins (1995, 1996, 2005) in tie-down roping—the first Black contestant to win that event in the Round-Up.

-

![George Fletcher]()

George Fletcher.

George Fletcher Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 67878

-

![Joseph Sewell]()

Joseph Sewell.

Joseph Sewell Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 85398

-

![]()

Jesse Stahl at the Pendleton Round-Up.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 12527

-

![]()

Jesse Stahl.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi12528

-

![This image is likely George Fletcher. The photographer identified the horse, but not the rider, demonstrating one way black riders were often marginalized in the white-dominated sport.]()

George Fletcher on Hot Foot (horse).

This image is likely George Fletcher. The photographer identified the horse, but not the rider, demonstrating one way black riders were often marginalized in the white-dominated sport. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 12529

-

![Jesse Stahl on Grave Digger (horse), c. 1916]()

Jesse Stahl on Grave Digger (horse), c. 1916.

Jesse Stahl on Grave Digger (horse), c. 1916 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 12526

Related Entries

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![Pendleton Round-Up]()

Pendleton Round-Up

The Pendleton Round-Up began in September 1910 as a frontier exhibition…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Black Past Online: An Online Reference Guide to African American History. www.blackpast.org.

Duffin, Andrew. "A Long, Strange Yarn: Ken Kesey and the Pendleton Round-Up." Oregon Historical Quarterly 106.1 (Spring 2005): 98-115.

McLagan, Elizabeth. A Peculiar Paradise: A History of Blacks in Oregon, 1788-1940.

Portland, Ore.: The Georgian Press, 1980.

Oregon Black Pioneers Online. http://www.oregonnorthwestblackpioneers.org.

Oregon Northwest Black Pioneers. Perseverence: A History of African Americans in

Oregon’s Marion and Polk Counties. Salem: Oregon Northwest Black Pioneers, 2011.

Patton, Tracy Owens and Sally Schedlock. "Let’s Go, Let’s Show, Let’s Rodeo: African

Americans and the History of Rodeo." The Journal of African American History 96.4 (Fall 2011): 503-521.

Rupp, Virgil. Let ‘er Buck: A History of the Pendleton Round-Up. Pendleton, Ore:

Pendleton Round-Up Association, 1985.