In 1932, with the Northwest lumber industry hit especially hard by the Depression and with “Hoovervilles” springing up in the city’s Sullivan Gulch and elsewhere, Portland became a center of activity for a direct-action political movement known as the Bonus Army. By late 1931, thousands of unemployed World War I veterans across the country had begun to call on Congress to pay their long-promised enlistment bonus ten years early (it was not due until 1942). In the opening months of 1932, Portland veterans became increasingly vocal, some of them calling for a veterans’ march on Washington, D.C.

It was in Portland that Walter W. Waters, a native Oregonian, first emerged as a forceful and colorful leader of the Bonus Army movement. Born and raised in Burns, Sergeant Waters had served in France and had seen combat at Saint Mihiel and Chateau-Thierry. With the onset of the Depression, Waters’s small business endeavors failed; he survived as a “fruit tramp” before coming to Portland. Waters took easily to public speaking; and with veterans calling for “the Bonus now,” he promoted the idea of a veterans’ march to present their demand to Congress.

Waters’s rhetoric was reported in West Coast newspapers, and groups of unemployed veterans hitchhiked and rode the rails to Portland to join him as recruits to the Bonus Expeditionary Force (BEF). Many of the men, some from as far away as southern California, wore their old khaki shirts and proclaimed they were ready to “march” on the nation’s capital.

By May, Waters had instituted a familiar military structure and discipline on his growing number of troops, and the Oregon contingent headed east. Along the way, American Legion posts provided coffee and snacks, and friendly railroad employees (many of them former veterans) allowed BEF members to ride in empty boxcars. Although other BEF contingents were making similar progress toward Washington, Waters—leading his men across the continent—gained particular national press coverage.

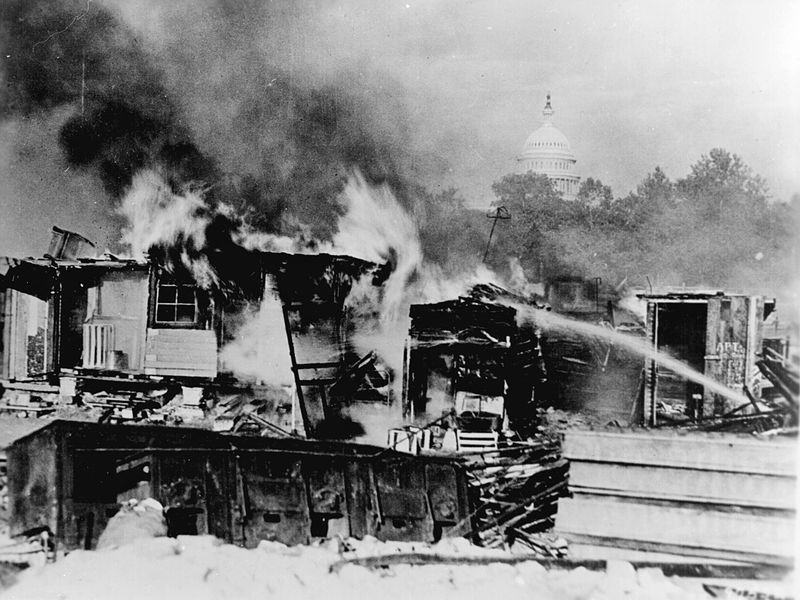

Once in Washington, D.C., Waters moved quickly to assume leadership of the entire movement. Expelling “Communists and radicals” from BEF ranks, he maintained an easy relationship with the authorities until, in the summer heat, the protest turned sour. The veterans’ largely peaceful occupation ended dramatically when President Herbert Hoover called in Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s army tanks, tear gas, and mounted cavalry to rout the former doughboys assembled only a few blocks from the White House. Two veterans died from police gunfire, and MacArthur’s troops burned the sprawling camp of shacks on nearby Anacostia Flats.

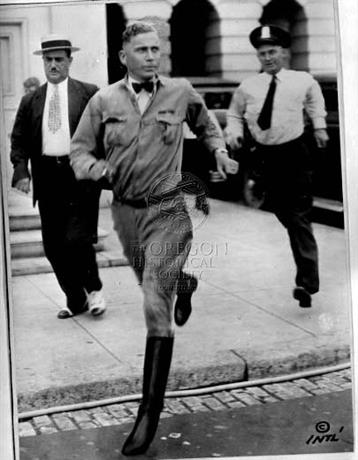

By the time of the BEF’s violent end, Waters—inspired by black- and brown-shirted legions in Europe—threatened to assume dictatorial powers over a national “Khaki Shirt” movement to deal with the Depression’s national emergency. Now dubbed “Hot” Waters and shunned by national veterans’ organizations, Walter Waters soon returned to relative obscurity. He enlisted in the Navy during World War II and returned to the Northwest in the mid-1950s, dying in Wenatchee, Washington, in 1959.

The Bonus Army debacle, with its dramatic newspaper photographs of veterans being chased from Pennsylvania Avenue at bayonet point, ended the beleaguered Hoover’s hopes for re-election.

-

![]()

WWI veterans, possibly part of the Bonus Army, 1932.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 371N4291

-

![]()

Bonus Army camp in D.C., 1932.

Courtesy Library of Congress

-

![]()

Burning of Bonus Army camps in D.C, 1932.

Courtesy U.S. National Archives

-

![]()

Walter Waters at the records desk in the War Department, 1935.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 021864

-

![]()

Walter Waters being arrested in D.C., 1932.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 021859

Related Entries

-

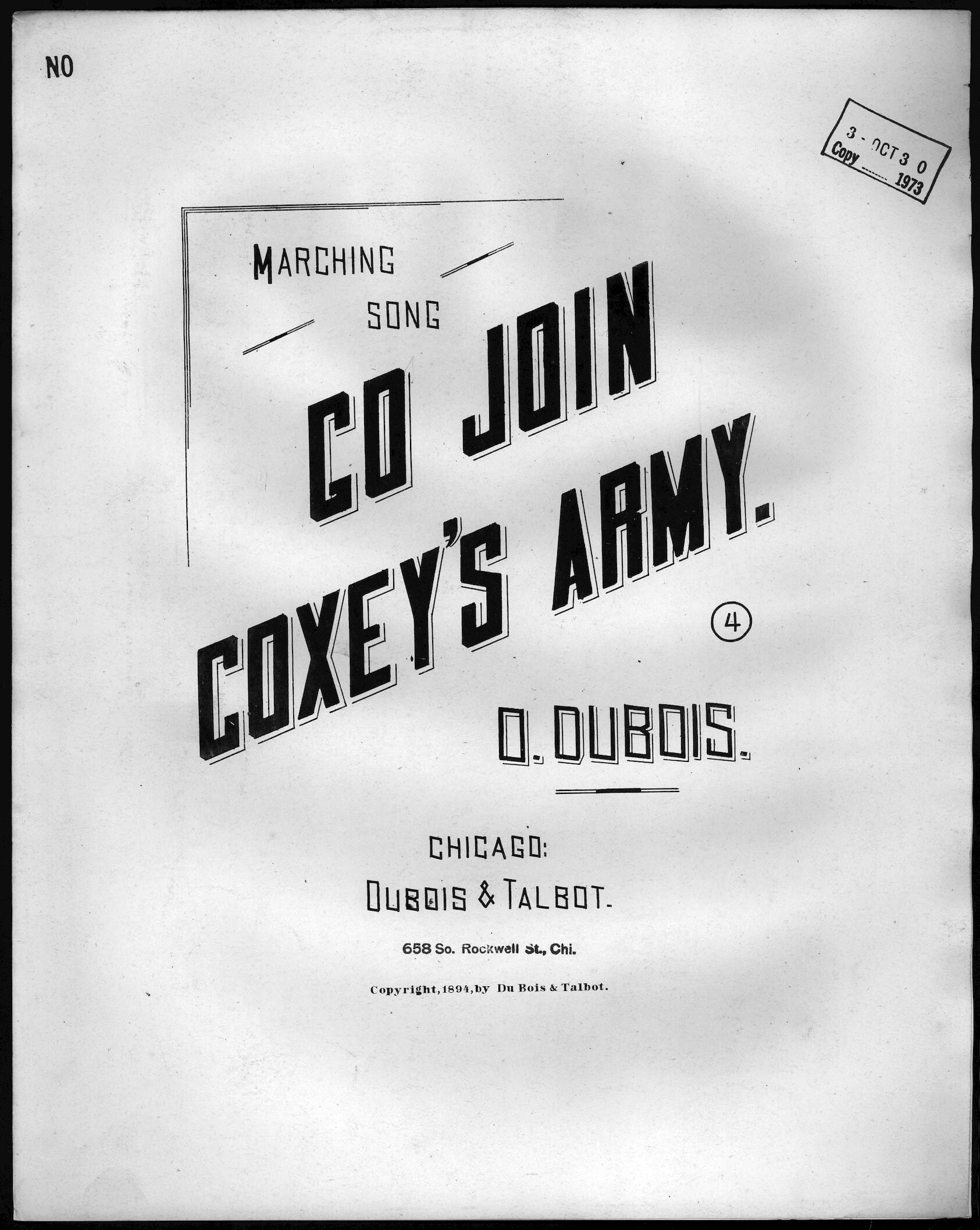

![Coxey's Army]()

Coxey's Army

One of the periodic economic collapses endemic in America’s economic hi…

-

Herbert Hoover in Oregon

Herbert Hoover, the thirty-first president of the United States, spent …

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Dickson, Paul, and Thomas B. Alley. The Bonus Army: An American Epic. New York: Walker and Co., 2004.

Ellis, Edward R. A Nation in Torment: The Great American Depression, 1929-1939. New York: Coward-McCann, 1970.

Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr. The Age of Roosevelt: The Politics of Upheaval. Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin, 1960.