William Brown was a respected and influential citizen in Portland's early Black community. A staunch advocate of equal education for all children, he played a significant role in establishing educational opportunities for Black children in the city, first in a separate school and later in integrated public schools. As a Portland businessman, he established a boot and shoemaking shop and invested in several enterprises, including real estate. He was a leader in civic groups that included the AME Zion Church, the Workingmen's Joint Stock Association of Portland, and Portland's Colored Immigration Aid Society.

William Brown was born into slavery in Maryland, probably in about 1828 (his obituary in the Oregonian lists his birth year as 1833; census records show 1828–1829). “At an early age,” according to the Oregonian in 1899, he "pledged his life against bondage and oppression." After escaping from Maryland, he used "heroic courage and skill" to reach Pennsylvania, which had been a free state since 1780. In Philadelphia, he apprenticed in shoemaking and enrolled in night school. It was probably there that he married Sarah Ganes, the daughter of Morton and Catherine Ganes of Washington, D.C. By about 1854, the Browns had settled in San Francisco, where William had a successful business as a boot and shoemaker and where two sons—William and George—were born.

In 1858, after fears about racial discrimination and persecution in California were compounded by the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision, Brown moved to Vancouver Island, where Governor James Douglas (whose mother was known to be a free Black woman from the West Indies) was welcoming Black settlers to help solidify Britain's position in the colonies of Vancouver and British Columbia. As many as eight hundred Black immigrants, including the Browns, made their way from California to British Columbia in 1858–1859, the first organized groups to respond to Douglas's promise of land and voting rights. While many followed the Fraser River gold rush, William and Sarah Brown chose to settle in Victoria, where two more sons—Charles and Walter—were born. Victoria was also where Sarah Brown would die on December 18, 1863, at the age of thirty-two.

Forming a partnership with G. H. Matthews, William Brown worked as a retailer in Victoria. Brown & Matthews was initially a clothes-cleaning establishment and later became a clothiers that sold "men's suits, under-garments, boots, and shoes, all at moderate rates."

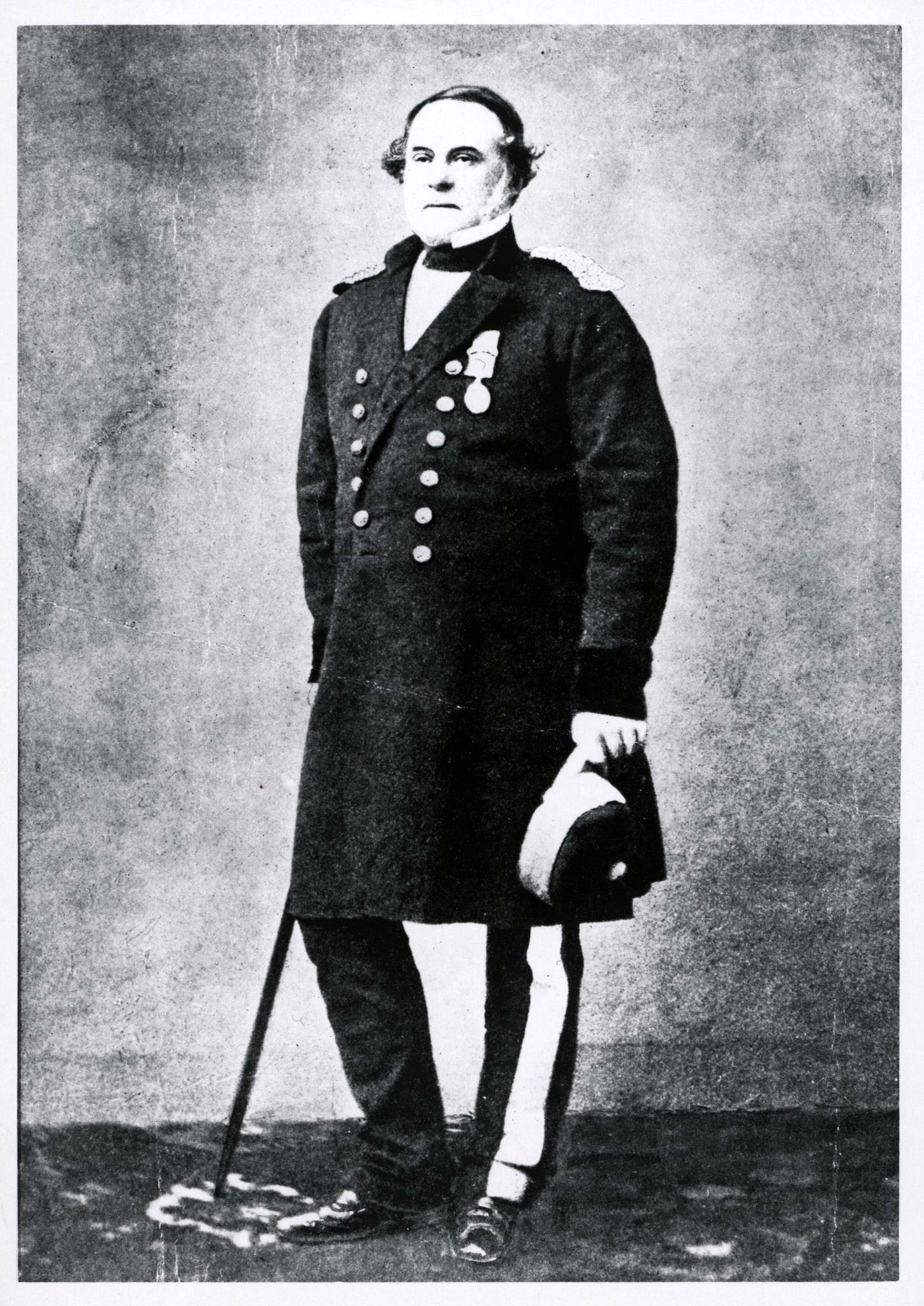

Brown was also a captain in the Victorian Pioneer Rifle Corps, Victoria's first militia. Known as the African Rifles, the mainly self-funded militia of forty to fifty Black men was formed in 1859, when tensions were running high because of the so-called Pig War, a controversy between Britain and the United States over possession of San Juan Island. Militia members sought an opportunity to perform public service and obtained Governor Douglas's support to defend British land interests if anyone, including Americans, threatened the Crown’s authority.

The corps was officially sworn in, with perhaps more than a nod to the United States, on July 4, 1861. Although they were never deployed, the African Rifles maintained a ceremonial presence in Victoria until 1864, when the government's new leadership denied them participation in Douglas's retirement ceremonies and banned them from serving as an honor guard for the new governor, Arthur Kennedy. By 1866, their ranks were depleted and, as requested, they returned their rifles to the government.

Despite their hopes, Black people were little more than tolerated in British Columbia and often encountered discrimination and segregation. In the early 1860s, Brown and other Victoria petitioners reminded Governor Douglas: "Coming to this colony to found our homes, and rear our families, we did so advisedly, assured by those in authority that we should meet with no disabilities, political or conventional, on the ground of color." But conditions did not improve. The Black editor of the San Francisco Pacific Appeal visited Victoria in 1864 and concluded: "There is as much prejudice and nearly as much isolation in Victoria as in San Francisco." After the American Civil War ended in 1865, about half of British Columbia's Black residents, including William Brown, returned to the United States.

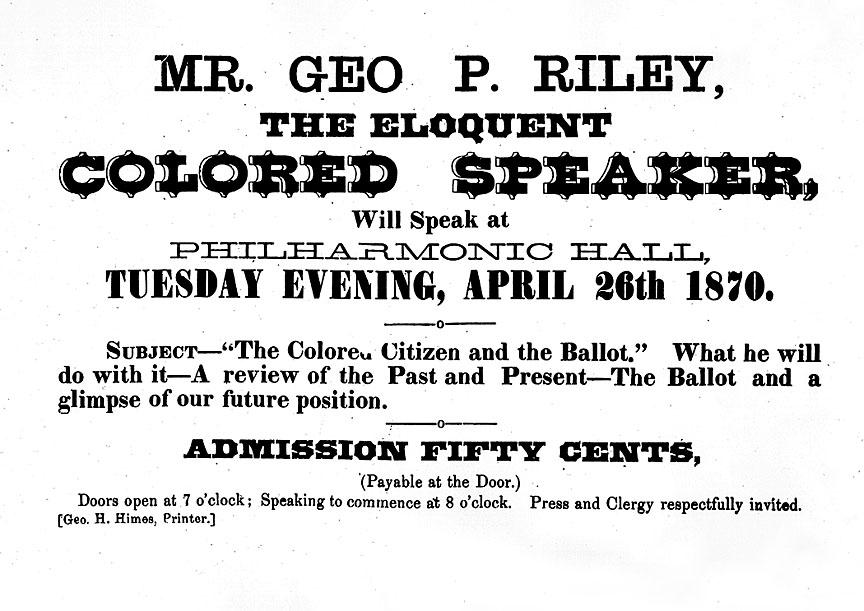

Why Brown chose to move with his four sons to Portland is unknown, but he apparently was undeterred by Oregon's Black Exclusion Laws. He probably heard about Oregon from Abner H. Francis, a Black merchant who had left Portland to settle in Victoria in 1861, and people like George Putnam Riley, a barber, and William Glasco, a teamster, who moved from Victoria to Portland after the war ended.

Once settled in Portland, Brown sought and finally secured educational opportunities for his sons. Victoria's public schools were open to Black children, but in Portland they were denied access to public education, even though Oregon law guaranteed education for all. Early in 1867, when Brown attempted to enroll his sons in school, they were turned away. He enlisted Thomas Alexander Wood, a white ally and Methodist clergyman, to negotiate with the Portland School Board on behalf of Black parents and their children, but even Wood’s proposal for a separate school was rejected as too costly.

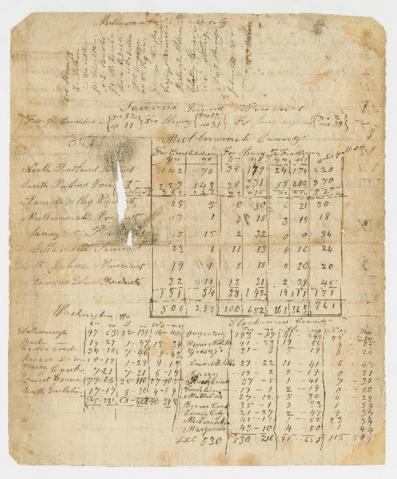

Brown and Wood turned to David Logan, an attorney and former mayor of Portland, and legal action was filed. Before the case went to court, the school board—whose members were Judge Erasmus Shattuck, William S. Ladd, and Josiah Failing—approved spending $800 to establish and maintain a school for Black students. The so-called Colored School, located in a building rented from Judge Shattuck at Southwest Fourth Street and Columbia Avenue, opened in the fall of 1867 and continued for five years, with about twenty-five students a year. It was Oregon's second so-called colored school; the first had been founded a few months earlier by Black citizens in Salem.

William Brown and others continued to advocate for equal education for Black children and finally achieved success. In April 1872, the Oregonian reported the outcome of the school district's annual meeting: "Mr. J. D. Holman moved that the colored school of the city be declared abolished, and that the children of that school be entitled to admittance to the other public schools. This motion was carried without a dissenting voice." The Colored School was closed at the end of the 1872 school year, and Portland's Black children began attending integrated public schools in 1873.

On January 9, 1873, William Brown married Ellen E. Paris Thomas, who had been born in Nova Scotia on October 15, 1847; her son, six-year-old William H. Thomas, became his stepson. Census records indicate that the Browns' daughter, Laura, was born in Portland in about 1875 (Laura's delayed birth certificate, filed in 1936, after her death, gives a birth date of December 18, 1876).

For several years after he arrived in Portland, William Brown, with help from employees and sometimes his sons, ran his boot and shoe shop as Brown & Company. In about 1874, he joined with his brother-in-law, Charles Kelly Besselleu, to form Brown & Besselleu, Boot & Shoemakers, a partnership that continued into the 1880s. Besselleu, who was born in South Carolina in 1822, came to Oregon from Massachusetts in about 1870. He and Brown were not only partners and associates in several business ventures, but their wives were sisters and the families were next-door neighbors on Water Street.

Brown was an active investor and businessman. In 1869, he was vice president and one of fifteen founding members of the Workingmen's Joint Stock Association of Portland, along with George Putnam Riley, Mary Carr, Mark Bell, and others. In 1877, he was one of eight incorporators of the Camp Creek Gold & Silver Mining Company in Wasco County, with Charles Besselleu as president and Mark Bell as secretary. For seven years, beginning in about 1880 and while still in partnership with Besselleu, he was “Night Inspector” (night watchman) at the Custom House, earning $2.50 per night.

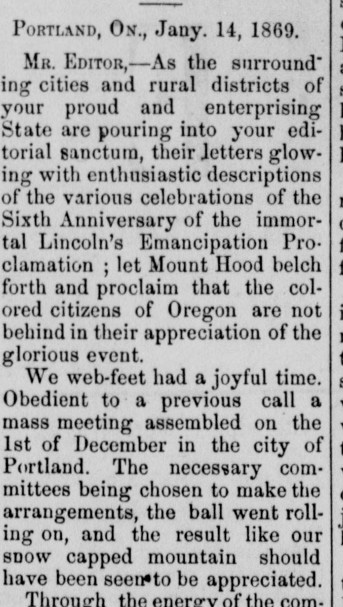

Brown was president for the Grand Emancipation Celebration in 1869 and orator for the event in 1880. He was elected to the Trustee Board for the First A.M.E. Zion Church in 1871, serving with James Beatty, Mark Bell, and others, and he was named president of the Trustee Board in 1873. With Charles Besselleu, Reuben Crawford, and others, he helped found Portland's Colored Immigration Aid Society in 1879. He served on the Society's Board of Trustees and was chosen as its president in 1881. With a strong interest in politics, Brown presided over the Plumed Knight Republican Club in 1888, with his son Charles as secretary.

In the fall of 1888, Brown moved with his wife and daughter to Whatcom, Washington Territory, perhaps to pursue real estate interests. A few months later, on February 24, 1889, during a business trip to Portland and while serving as the newly elected president of the Workingmen's Joint Stock Association of Portland, William Brown died. According to the Oregonian obituary, he had been "stricken down with paralysis" and had died at the home of his friend William Waterford at 209 K Street.

Brown was survived by his wife Ellen and two children—fourteen-year-old Laura and twenty-eight-year-old Charles, a Portland barber. Ellen lived for a time in Tacoma, Washington, where she married James W. Thompson of Kentucky on February 19, 1891; they moved to British Columbia, where James was a restaurant keeper. On June 17, 1890, Laura married Charles W. Lapsley, a hotel porter and railroad waiter in Pierce County, Washington. Their son, Lorenzo Brown Lapsley, was born in Tacoma on April 17, 1891. After a divorce, Laura lived in Portland, where she died on November 23, 1935, following an auto collision. Lorenzo, William Brown's grandson, received his Doctor of Medicine degree from the University of Michigan Medical School in 1916 and founded a successful private practice in Chicago.

-

![]()

"Emancipation Celebration!" Morning Oregonian, December 11, 1880.

Portland Morning Oregonian

-

![]()

Victoria Pioneer Rifle Company (The Black Pioneers).

Courtesy National Park Service -

![]()

"The Public School and the Colored Children," Morning Oregonian, May 29, 1867.

Portland Morning Oregonian

-

![]()

Adjourned School Meeting," Morning Oregonian, April 23, 1872.

Portland Morning Oregonian

-

![The school once stood where Pioneer Square is now, on SW 6th street between Yamhill and Morrison, across from the Pioneer Courthouse.]()

-

![]()

Central School, Portland.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 26077 photo file 1838

-

![]()

Grand Emancipation Celebration invitation, 1869.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Orhi81181 -

![]()

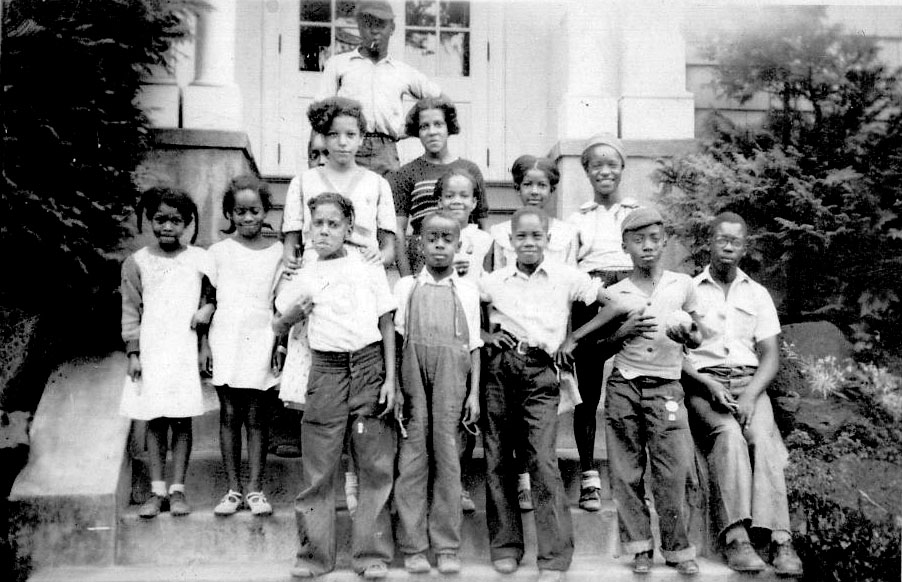

Students at Harrison Street School, Portland, 1880.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 9249. photo file 1842

-

![]()

Holladay School, Portland, c.1900.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, cn024609, photo file 1842

Related Entries

-

![Abner Hunt "A. H." Francis (c. 1812–1872) and Isaac "I. B." Francis (1798-1856)]()

Abner Hunt "A. H." Francis (c. 1812–1872) and Isaac "I. B." Francis (1798-1856)

A. H. Francis, a free Black, was a merchant and activist who in 1851 op…

-

![Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon]()

Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon

Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws th…

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![First African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church]()

First African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church

First African Methodist Episcopal Zion is Portland's oldest African Ame…

-

![George Putnam Riley (1833–1905)]()

George Putnam Riley (1833–1905)

Identified by the Oregonian as the “Fred[erick] Douglass of Oregon,” Ge…

-

![James Douglas (1803-1877) in Oregon]()

James Douglas (1803-1877) in Oregon

James Douglas had a long connection to the Oregon Country. As an employ…

-

![James William Beatty (1830–1914)]()

James William Beatty (1830–1914)

From his arrival in Oregon in about 1864 until his death in 1914, James…

-

![Mark A. Bell (1825–1897)]()

Mark A. Bell (1825–1897)

Marcus "Mark" A. Bell was a visible and enterprising leader in Portland…

-

![Mary H. Carr (1823?–1911)]()

Mary H. Carr (1823?–1911)

Mary H. Carr was an enterprising and respected member of Portland's ear…

-

![Mary Laurinda Jane Smith Beatty (1834–1899)]()

Mary Laurinda Jane Smith Beatty (1834–1899)

Mary Beatty, one of the first Black women west of the Mississippi to ad…

-

![Reuben Crawford (1828–1918)]()

Reuben Crawford (1828–1918)

Reuben Crawford was a leader in Portland's Black community from the 187…

-

![Salem's Colored School and Little Central]()

Salem's Colored School and Little Central

The first school open to African American students in Oregon—referred t…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

"Adjourned School Meeting." Oregonian, April 23, 1872, p.3.

Casey, Helen Marie. Portland's Compromise: The Colored School, 1867-1872. Portland, Oregon: Public Schools Public Information Dept., 1980.

"Church Election." A.M.E. Zion Church. Oregonian, July 7, 1871, p. 2.

Cosmopolite [Phillip A. Bell]. "Notes on a Trip to Victoria, Number Five." San Francisco Pacific Appeal, February 6, 1864, pp. 2-3.

"Customs Service, July 1, 1885." United States Register of Civil, Military, and Naval Service, 1863-1959. Vol. l. Washington, D.C.: Treasury Department, pp. 190-91.

"Death of a PIoneer." Charles K. Besselleu. Oregonian, January 1, 1907, p. 2.

"Died." Sarah Brown. San Franisco Pacific Appeal, January 2, 1864, p. 4.

"Election of Officers." Portland Immmigration Aid Society. Oregonian, June 14, 1881, p. 3.

"A Good Example." Letter from "Plaquemine" re. Portland Public Schools. San Francisco Elevator, May 4, 1872, p. 2.

Incorporation Papers of "The Camp Creek Consolidated Gold + Silver Mining Company," February 23, 1877. Oregon State Archives. Salem, Oregon.

Incorporation Papers of "The Workingmen's Joint Stock Association of Portland," December 9, 1869. Oregon State Archives. Salem, Oregon.

Johnson, Ethan and Felicia Williams. "Desegregation and Multiculturalism in the Portland Public Schools." Oregon Historical Quarterly lll:l (Spring 2010): 6-37.

Kilian, Crawford. Do Some Great Thing: The Black Pioneers of British Columbia. Vancouver, B.C.: Douglas and McIntyre, 1978. Third edition, November 2020.

MacColl, E. Kimbark. Merchants, Money, & Power: The Portland Establishment, 1843-1913. Portland: The Georgian Press, 1988, pp. 192-94.

"Married." William Brown and Mrs. Ellen Thomas. San Francisco Elevator, February 22, 1873, p. 3.

McLagan, Elizabeth. A Peculiar Paradise: A History of Blacks in Oregon 1788-1940. Second Edition. Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press, 2022.

"The Negro Children and the Public Schools." Oregonian, June 8, 1867, p. 3.

"Obituary. William Brown." Oregonian, February 27, 1889, p. 8.

Pilton, James William. "Negro Settlement in British Columbia, 1856-1871." MA Thesis, History, The University of British Columbia, September 1951.

"Portland Colored Immigration Society." Oregonian, September 10, 1879, p. 3.

"Preamble and Resolutions." [A..M.E. Zion Church.] Oregonian, February 13, 1874, p.

"The Public School and the Colored Children." Oregonian, May 29, 1867, p. 3.

"The Public Schools." Oregonian, September 2, 1867, p. 3

Richard, K. Keith. "Unwelcome Settlers: Black and Mulatto Oregon Pioneers." Part l. Oregon Historical Quarterly 84:l (Spring 1983): 29-55.

_____. "Unwelcome Settlers: Black and Mulatto Oregon Pioneers." Part ll. Oregon Historical Quarterly 84:2 (Summer 1983): 173-205.

"University of Michigan." Oregon Daily Journal, February 21, 1915, p. 50.

Wong, May Q. City in Colour: Resdiscovered Stories of Victoria's Multicultural Past. Canada: Touchwood, 2018.

Wood, T.A. [Thomas Alexander]. "Admission of Collored [sic] Children to the Public School, c. 1890." Oregon Historical Society, MSS37.

"Workingmen's Stock Association." Oregonian, January 19, 1889, p. 8.