For thirteen months beginning in 1899, a company of 103 soldiers from the U.S. Army’s 24th Infantry—one of four African American regiments known as Buffalo Soldiers—garrisoned at Vancouver Barracks in Vancouver, Washington. The company arrived at the barracks during the brief period of time when respect for African American soldiers was buoyed by their recent success in the Spanish-American War in Cuba. While in the Northwest, the soldiers participated in military, political, and social activities, introducing many residents of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho to Blacks and raising local awareness of the national policies and practices that beleaguered African Americans.

The regular assignments of garrison duty at an army post—drilling, marching, and marksmanship; improving the post's infrastructure; performing maintenance and clerical work; and attending the post school—comprised the majority of the soldiers’ duty hours at Vancouver Barracks. A regional crisis with national implications, however, soon called them to arms. Violence had broken out in the Coeur d'Alene mining area in northern Idaho, and a mill owned by the Bunker Hill and Sullivan Mining Company had been dynamited. The federal government dispatched troops; and in May 1899 Company B, some of the closest soldiers to the area of conflict, responded to the scene. Along with soldiers from other forts, they imposed martial law and guarded prisoners and rail lines in what was one of the major labor-capital conflicts of the twentieth century.

In contrast to the confrontational nature of their duty in Idaho, these soldiers interacted with the public differently in Portland and Vancouver, primarily through formal events and activities. Soldiers of Company B took part in ceremonies that previously had been the responsibility of white soldiers, including parades, escorts, military band concerts, and funerals. In 1899, for example, Company B provided full military honors at the burial of Moses Williams, a retired Buffalo Soldier from the 9th Cavalry and a Medal of Honor recipient, who died on August 23. Williams, who had been the ordnance sergeant at Fort Stevens, near Astoria, was buried in the Vancouver Barracks post cemetery.

The soldiers of Company B made the most of their leisure time, organizing dances, parties, and baseball games. The Portland New Age, a Black-owned newspaper, reported on the soldiers’ involvement in social activities, including a wedding in Vancouver where “quite a number of friends from Portland attended.” The company’s baseball team, called the Hard Hitters and the Brownies in local newspapers, played several games, including some against white teams.

The growing African American community in Portland, centered on the neighborhood around Union Station, served as a hub of social life for the soldiers of Company B. The company's ranking noncommissioned officer, Sgt. Mack Stanfield, and his wife, thirty-five-year-old Sallie, later retired to Portland, where they remained for the rest of their lives. Stanfield and a fellow Buffalo Soldier, Sgt. Alfred J. Franklin, jointly owned and operated the Luneta Saloon at 101 Park Avenue North, along the North Park Blocks near Union Station, and both owned homes on Portland’s east side. Mack and Sallie Stanfield are buried in Lincoln Memorial Park Cemetery in Portland.

While the soldiers were well received in Portland’s African American community, evidence suggests that they faced some racially based acrimony from whites. When the company left Vancouver Barracks in the spring of 1900, the New Age reported, “Their stay there gave the citizens of Vancouver an opportunity to see more Afro-Americans than many of them had ever seen, and whilst on the whole, they were well received, we have heard of one or two instances where low-bred people took an opportunity to exhibit the prejudice existing in their groveling nature.”

One of those instances might have been that described by Pvt. James G. Cole in a letter to the Oregonian on September 26, 1899. In it, he related how he witnessed white officers of the 35th Volunteer Infantry voicing “a certain prejudice against serving in colored regiments.” Cole wrote that he "would have spoken, but their rank being so superior to mine, my tongue cleaved.” He ended his letter with a plea that Black army regiments be led by Black officers. "If this is done," he argued, "it will mark a distinct step in advance of any taken hitherto. It will recognize…the manhood of the colored troops, and break down the bar of separation now existing….The colored soldier has proven to this nation…that he is competent to command—providing they give him show."

Company B's duty at Vancouver Barracks ended on May 17, 1900, when the soldiers departed for Fort Wright, near Spokane, Washington. Within months, on October 16, they had been transferred to the Presidio in San Francisco, then to duty in the Philippine Islands.

-

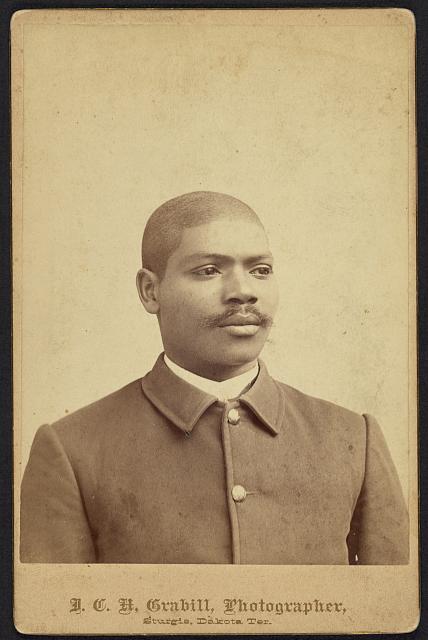

![Buffalo Soldier, 1884. Photo by John C.H. Grabill.]()

Buffalo Soldier, 1884.

Buffalo Soldier, 1884. Photo by John C.H. Grabill. Courtesy Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-11350

-

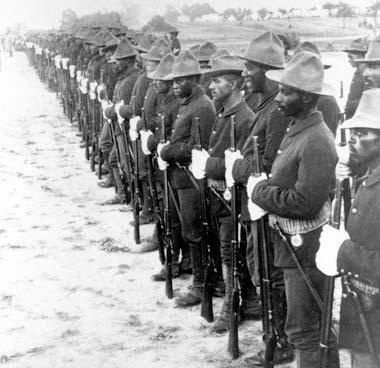

![Soldiers from one of the all-black army regiments, which became known as the Buffalo Soldiers.]()

Related Entries

-

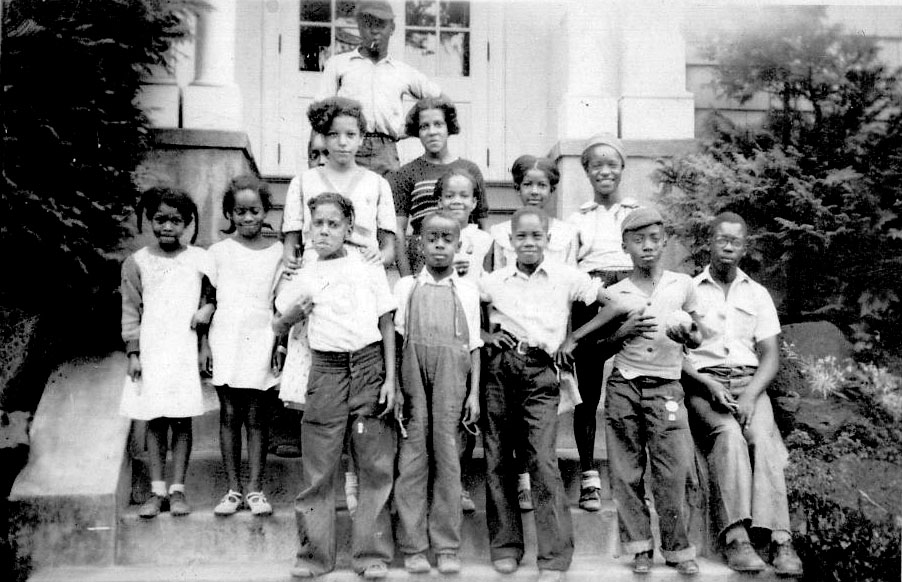

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![Moses Williams (1845-1899)]()

Moses Williams (1845-1899)

Born in rural Louisiana in 1845, Moses Williams joined the U.S. Army in…

-

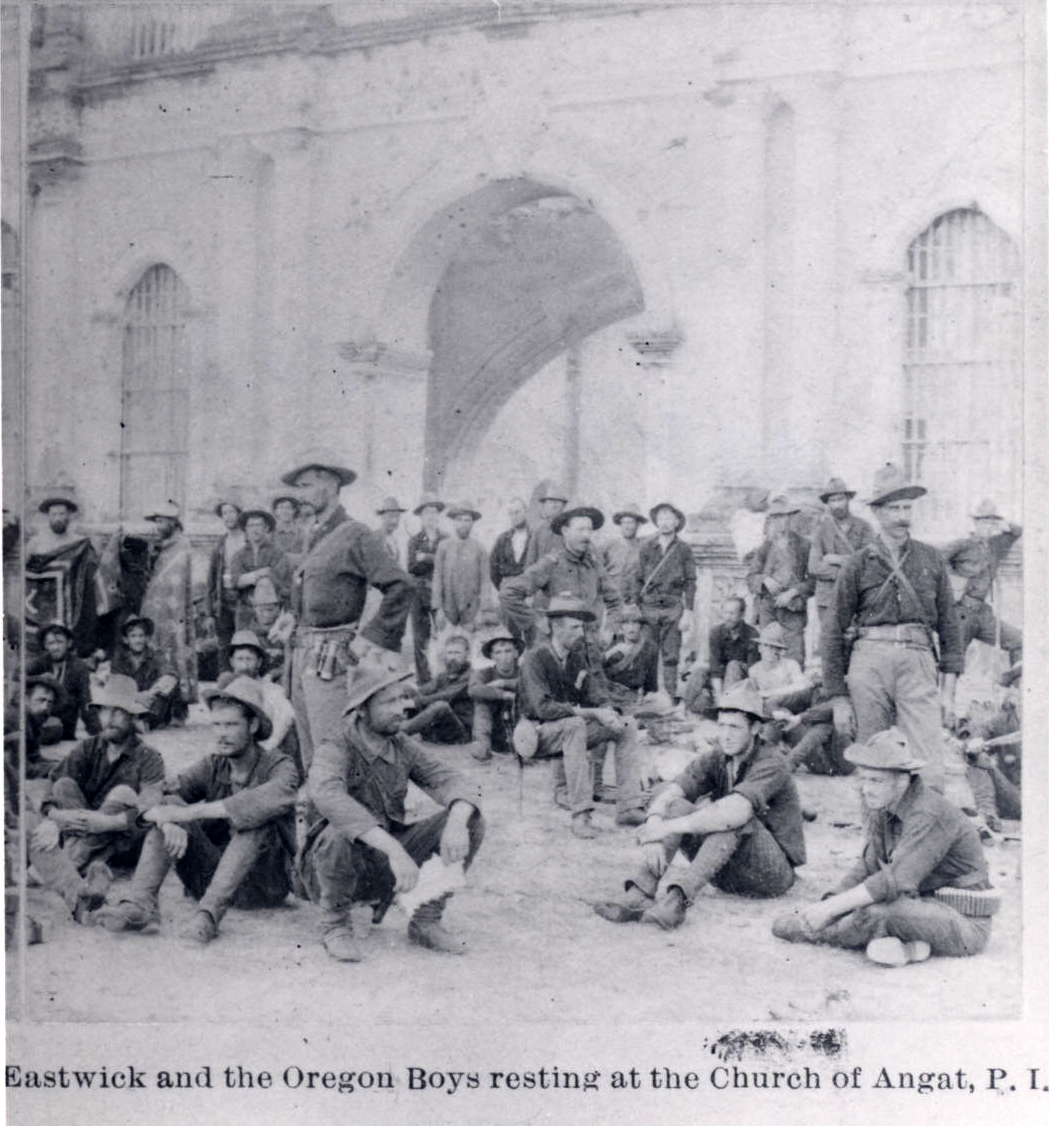

![Oregon Soldiers in the Spanish-American and Philippine Wars, 1898-1899]()

Oregon Soldiers in the Spanish-American and Philippine Wars, 1898-1899

In the course of the Spanish-American War, the United States attacked a…

-

![Triple Nickles -- 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion]()

Triple Nickles -- 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion

The 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, nicknamed the "Triple Nickles" …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Shine, Gregory Paynter. "Respite from War: Buffalo Soldiers at Vancouver Barracks, 1899-1900." Oregon Historical Quarterly 107.2 (Summer, 2006): 196-227.

Portland New Age, December 30, 1899.

Portland New Age, May 19, 1900.

Oregonian, September 26, 1899.