Asahel Bush was a key figure during Oregon's formative years, using the power of the press to influence the political landscape. Born in Westfield, Massachusetts, at fifteen he became an apprentice printer and then studied law while supporting himself with newspaper work. He read law and was admitted to the Massachusetts Bar in 1850.

Shortly thereafter, Samuel Thurston, Oregon Territory's delegate to Congress, recruited Bush to be his partner in founding a newspaper in the territory. Thurston conceived the paper as a way to ensure his re-election and chose its name, the Oregon Statesman, perhaps with himself in mind. After traveling by way of the Isthmus of Panama in 1850, Bush settled in Oregon City, the center of political activity in the territory.

The first edition of the Statesman was published on March 28, 1851. The paper called for the formation of political parties in Oregon and strongly supported the Democratic Party of Oregon, which was organized in 1852 with Bush's active participation. When Salem was chosen as the state capital, Bush moved the paper there. Its power was soon felt, as politicians sought its support and public opinion reflected its stands.

To further his political aims, Bush gathered around him a group of like-minded men, including Matthew P. Deady, James W. Nesmith, and Orville C. Pratt, who would become, respectively, a federal judge, a United States senator, and an Oregon Supreme Court justice. For a time, the team became the dominant force in Oregon politics.

While scholars of the period unanimously recognize the influence of the so-called Salem Clique, they are divided about its methods. Some have compared it to Tammany Hall (the political machine that dominated New York City during the second half of the nineteenth century), and described the group as ruthless and coercive. Others have concluded that Bush and his colleagues served the people of Oregon well.

Addressing the most important political controversy of the day, Bush, the Statesman, and the Democrats championed statehood while the Whig (later Republican) Oregonian opposed it, taking the position that Oregon did not have the population or the wealth to support a state government. Oregonian editors also preferred the ongoing prospect of Whig presidents appointing Whig officials to the territorial government. The battle was characteristic of the continuous and often vitriolic feud between the Oregonian and the Statesman, creating a form of journalism known as the "Oregon style."

In 1855, Bush wrote this about Oregonian editor Thomas J. Dryer: "The Oregonian man is the most unvarying liar we have ever met with. He so seldom tells the truth, even by mistake, that we are inclined to make a special note of the fact when he does." Dryer‘s response was even more incendiary: "If there is any animal meaner than the slimy creeping reptile, it is the cowardly slanderer, paid libeller and miserable lick-spittle of the Oregon Statesman who is known by the cognomen of Asahel (Ass-a-hell) Bush."

Bush campaigned against the intrusion of the Know-Nothings, who rejected those who were not American-born and opposed the influence of the Roman Catholic Church. To fight the Know-Nothings, he supported the viva voce law, which would have required that all votes in general elections be publicly declared before witnesses. The fact that it would have also kept Democratic voters in line by making their votes public was a side benefit.

The national crisis over slavery complicated Oregon's move toward statehood. Bush opposed slavery but favored the constitutional ban against allowing Blacks to immigrate to the state. The Oregon electorate agreed with him in the 1857 constitutional election, by large margins voting to ban slavery and exclude free Blacks.

The exclusion provision, while only rarely enforced, remained in the Oregon Constitution until it was eliminated through a referendum in 1926. Although Bush was adamantly pro-Union during the Civil War, he urged reconciliation with the Confederate states when the war ended. In keeping with his earlier views, he did not support African American aspirations.

Bush sold his newspaper in 1863 but remained an influential force in Oregon politics. He later co-founded the Ladd and Bush bank, the first in Salem. Through his life, he served on a variety of boards, including those of Willamette University, the University of Oregon, and the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition. He was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1892. Bush died in 1913.

-

![]()

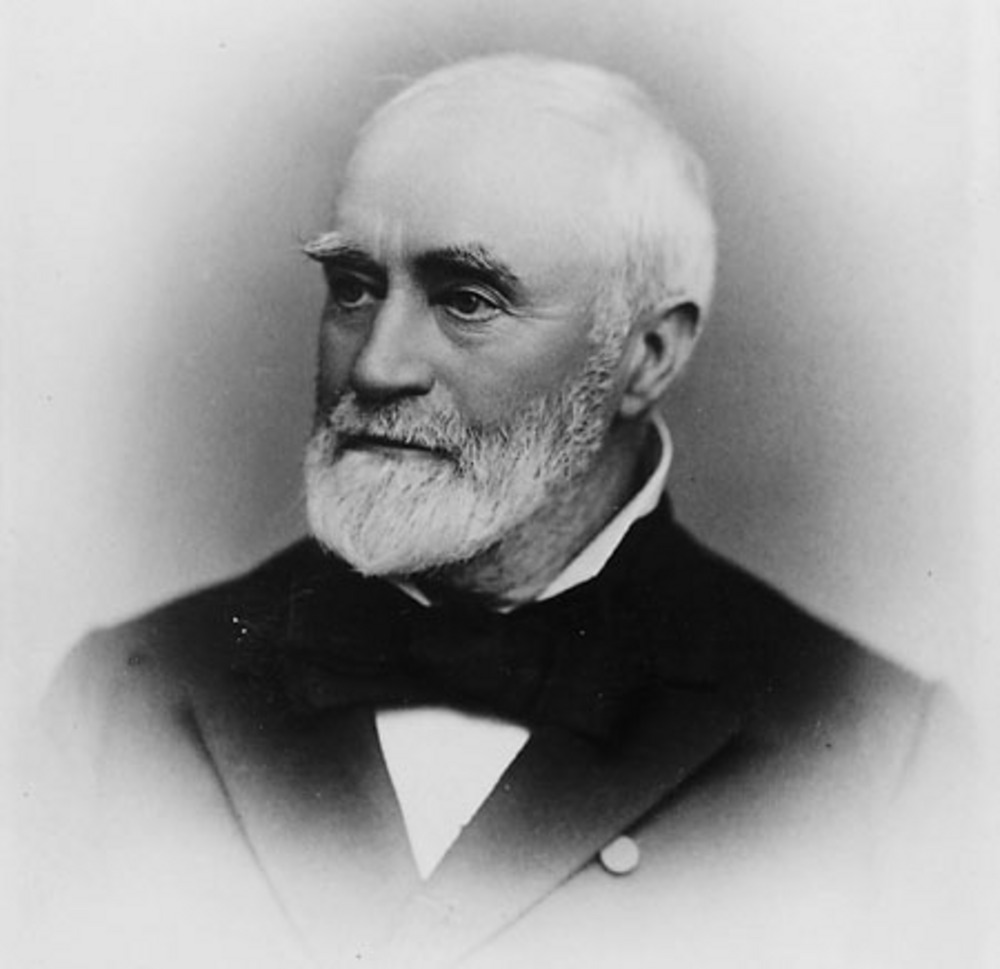

Asahel Bush.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 70286

-

![]()

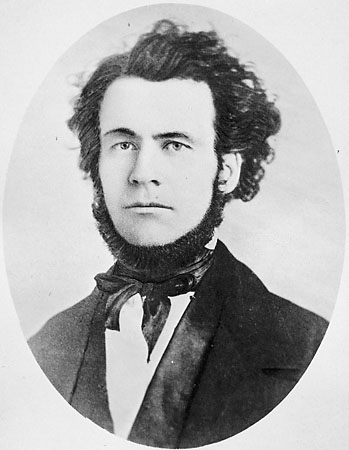

Davenport's sketch of Asahel Bush, Oregon Statesman publisher and editor.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, Mss. 5143, f3

-

![Library of Asahel Bush House Museum showing 1880 William Cogswell portrait of Asahel Bush II hanging above original marble fireplace.]()

Asahel Bush House Museum, library.

Library of Asahel Bush House Museum showing 1880 William Cogswell portrait of Asahel Bush II hanging above original marble fireplace. Photo by Kris Lockard, courtesy Asahel Bush House Museum

Related Entries

-

![Asahel Bush House]()

Asahel Bush House

In 1878, Asahel Bush (1824-1913)—Oregon publisher, banker, and politici…

-

![Bush's Pasture Park and Conservatory]()

Bush's Pasture Park and Conservatory

Bush’s Pasture Park and the Bush Conservatory in Salem are part of the …

-

![Oregon Statesman]()

Oregon Statesman

Throughout its history, the Oregon Statesman has been a chronicler of O…

-

![Salem Clique]()

Salem Clique

Thomas Dryer, the first editor of the Oregonian, named the Salem Clique…

-

![The Oregonian]()

The Oregonian

The Oregonian, the oldest newspaper in continuous production west of Sa…

-

![Thomas Jefferson Dryer (1808–1879)]()

Thomas Jefferson Dryer (1808–1879)

Thomas J. Dryer was the first editor of the Portland Oregonian and an a…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Dodds, Gordon B. Oregon: A Bicentennial History. New York: W.W. Norton, 1977.

Johannsen, Robert W. Frontier Politics and the Sectional Conflict: The Pacific Northwest on the Eve of the Civil War. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1955.