Celilo Falls (also known as Horseshoe Falls) was located on the mid-Columbia River about twelve miles east of The Dalles. It was part of an approximately nine-mile-long Indigenous fishery that included sites such as the Upper Dalles, the Lower Dalles, Three Mile Rapids, Five Mile Rapids, and Big Eddy.

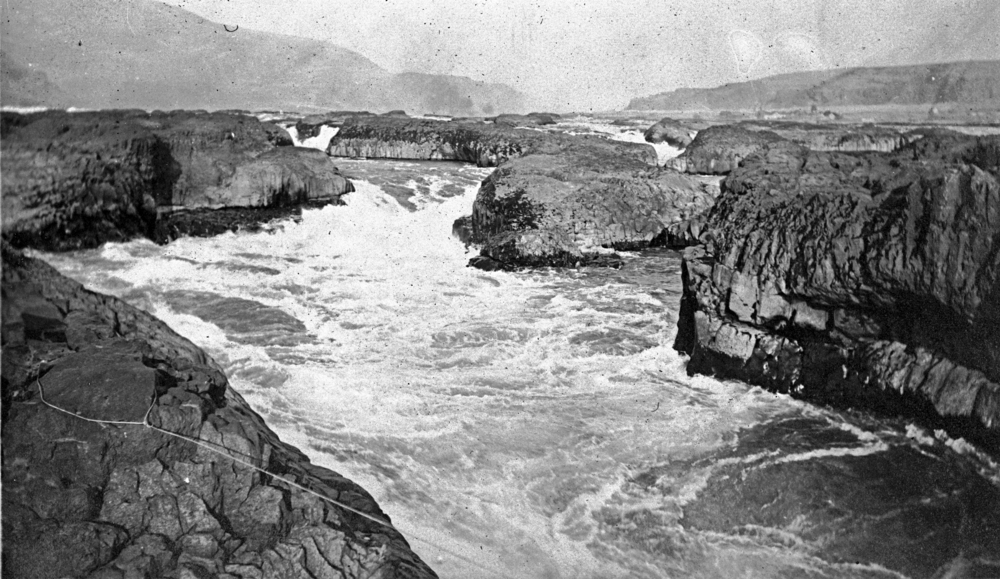

At Celilo Falls, the Columbia's riverbed constricted to a passageway as narrow as forty feet across, producing what nineteenth-century observer Alexander Ross described as "great impetuosity” where “the foaming surges dash through the rocks with terrific violence." The rapids, which dropped the river more than eighty feet in a half-mile, required most boats and other vessels to portage but also created some of the most productive fishing sites in the Pacific Northwest.

Archeological records date human occupation of village sites along the falls to at least 11,000 years ago. The first written population records come from the journals of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who estimated in 1805-1806 that 7,200 to 10,400 Indian people were present between the Cascade Rapids and The Dalles. Abundant fish runs drew Indigenous people to permanent settlements in the area, and village populations fluctuated with seasonal movement. In the decades after they encountered non-Natives, the numbers of people declined as a result of diseases that dramatically reduced native populations.

Villages near Celilo Falls incorporated cultural characteristics from the Chinookan people, who lived at the mouth of the Columbia and along the coast, and the inland Sahaptin-speaking people of the Columbia Plateau. Because of the cultural mixing and exchange that characterized the region, anthropologists describe mid-Columbia cultural areas as "shatter zones." Adjacent to the falls on the river's south shore is Celilo Village, Oregon's oldest continuously occupied site. Spearfish Village was located on the river's north bank.

Seasonal visitors came by the hundreds to Celilo Falls to socialize and trade. Economic activity often took the form of gambling, which missionaries and settlers later mischaracterized as vice. Celilo Falls was a significant trade entrepôt, where exchanged goods included dentalia, obsidian, buffalo meat and hides, pipestone, wapato, and slaves. The trade network stretched north into present-day Alaska, south to California, and east of the Rocky Mountains. The introduction of horses in the 1730s enlarged the regional trade network even more.

Rushing waters at the falls disoriented salmon swimming upstream to their natal streambeds, offering people the opportunity to catch the fish using nets and spears. Wishram and Wasco fishers often built wooden scaffolds out over the river and fished with long-handled dip nets. They fished Lamprey eel, sturgeon, and four species of salmon. Kinship networks determined who had rights to fish from the sites at the falls, and scaffold locations were inherited, passing from generation to generation. Until recently, men were the primary fishers, while women collected, cleaned, butchered, and dried the fish.

Methodist Henry Perkins founded a mission at The Dalles in 1838, the first non-native settlement on the mid-Columbia, and other Protestant missionaries followed. The rapids at Celilo Falls provided Oregon Trail travelers with one of the trip's quintessential quandaries: to brave the rapids in makeshift boats or to travel inland and cross Mount Hood (after 1846, on the Barlow Trail). The river threatened to overturn hastily built watercraft, losing household goods and travelers to the dangerous waters, but the overland trail was notoriously rough and added miles to an already long journey.

In 1850, the United States Army founded Fort Dalles to protect overlanders and miners who used the area as a jumping-off point to the gold and silver fields of the interior. The town of The Dalles was incorporated in 1856, approximately twelve miles downstream from Celilo Falls and Celilo Village.

When European Americans settled at The Dalles, the Indigenous communities near Celilo Falls were compromised. The federal government negotiated treaties with Columbia Plateau Indians, creating the Yakama, Nez Perce, Umatilla, and Warm Springs reservations, all of which were located considerable distances from Columbia River fishing sites. By the 1880s, the U.S. government had removed most Columbia River Indian people to inland reservations, though some continued to live at traditional fishing villages, including those near Celilo Falls.

In federal treaties, Indian people reserved for themselves the right to leave reservation communities to harvest and dry fish at their "usual and accustomed places." State agencies, private property owners, and even the Bureau of Indian Affairs, however, hampered Indian access to traditional sites. Tribal governments used the federal court system to define and protect treaty-fishing rights. The rise of a non-native commercial salmon fishery and the development of the Columbia River posed the most significant threats to the Indigenous fishery and to the very existence of Celilo Falls.

The first salmon cannery on the Columbia River was founded in 1866, and by 1883 there were forty-three canneries operating on the river. The commercial fishery used a variety of methods to harvest salmon runs, but none was as efficient as the fish wheel, a contraption introduced in 1894 that could scoop salmon from the river continuously with little human labor. In 1899, seventy-six fish wheels were operating on the Columbia River, twenty of them between Five Mile Rapids and Celilo Falls.

The non-native commercial fishery competed with the Indigenous fishery for salmon and productive fishing sites, but development transformed the river in ways that devastated salmon runs and destroyed traditional fishing sites such as Celilo Falls. Since the 1860s, steam vessels had portaged goods and people around the falls by way of a short railroad. In 1915, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers completed the Dalles-Celilo canal to ease river transportation past the many rapids and falls of the mid-Columbia River.

By 1953, the Army Corps of Engineers began construction of a large dam that would transform the river and allow traffic to move freely up and down the river. Because the Indian fishing sites at and near Celilo Falls were to be inundated by the dam's reservoir, the federal government negotiated a settlement with the Warm Springs, Yakama, Umatilla, and Nez Perce tribes to compensate them for the lost sites (fishing rights remained with the tribes). On March 10, 1957, The Dalles dam reservoir flooded Celilo Falls and a portion of Celilo Village. The site is now called Celilo Lake.

-

Celilo Falls, empty platforms at, OrHi 65995 , v105 i2 p 200.

Platforms at Celilo Falls. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 65995

-

![Cable car above Celilo Falls.]()

Celilo Falls, tram, ba020581.

Cable car above Celilo Falls. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 65984

-

Celilo Village, OHQ 2-03.

Celilo Village. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![Celilo Falls reparations discussions.]()

Celilo Falls reparations, CN 012216.

Celilo Falls reparations discussions. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., CN 012216

-

![Fishing at Celilo Falls.]()

Celilo Falls, fishing at, colorized, Picture 008.

Fishing at Celilo Falls. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 7784

-

![Creating The Dalles Dam, Aug. 1956. This blast was more than 20 tons of powder and removed 60,000 cubic yards of basalt.]()

Celilo Falls, blast at, Aug. 1956, bb002863.

Creating The Dalles Dam, Aug. 1956. This blast was more than 20 tons of powder and removed 60,000 cubic yards of basalt. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb002863

-

![Celilo Falls, about 1910.]()

Celilo Falls, 1910.

Celilo Falls, about 1910. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 66878

-

![Portage railroad at The Dalles, 1867.]()

Celilo Portage, OrHi 21587.

Portage railroad at The Dalles, 1867. Carlton E. Watkins photographer, Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 21587

-

![Celilo Canal under construction, showing east entrance and Tumwater fishwheel, 1913.]()

Celilo Canal, 1913, OrHi 9554.

Celilo Canal under construction, showing east entrance and Tumwater fishwheel, 1913. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 9554

-

Celilo Falls, fishing at, OrHi 65994, v105 i2 p 198.

Fishing at Celilo Falls. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 65994

-

![Fishing at Celilo Falls.]()

Celilo Falls, fishing at, ba018763.

Fishing at Celilo Falls. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 74928

-

![Wy'Am people fishing at Celilo Falls.]()

Celilo Falls, fishing at, OrHi 83885.

Wy'Am people fishing at Celilo Falls. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 83885

-

![Yakima and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers discuss settlement.]()

Celilo settlement discussions, CN 007247.

Yakima and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers discuss settlement. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., CN 007247

-

![Celilo Falls]()

Celilo Falls.

Celilo Falls Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 42687

Related Entries

-

![Celilo Fish Committee (1935 - 1957)]()

Celilo Fish Committee (1935 - 1957)

Members of Umatilla, Yakama, and Warm Springs tribes joined unenrolled …

-

![Martha Ferguson McKeown (1903-1974)]()

Martha Ferguson McKeown (1903-1974)

Author, historian, teacher, Martha McKeown, a third-generation Oregonia…

-

![The Dalles Dam]()

The Dalles Dam

The United States Army Corps of Engineers constructed The Dalles Dam be…

-

![Tommy Thompson (1864?–1959)]()

Tommy Thompson (1864?–1959)

Tommy Kuni Thompson served as the headman of Wyam (an Ichiskiin Sinwit …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Aguilar, Sr., George W. When the River Ran Wild! Indian Traditions on the Mid-Columbia and the Warm Springs Reservation. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 2005.

Barber, Katrine. Death of Celilo Falls. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005.

Boyd, Robert. People of The Dalles: The Indians of Wascopam Mission. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996.

Robbins, William G. Landscapes of Promise: The Oregon Story, 1800-1940. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997.

Smith, Courtland L. Salmon Fishers of the Columbia. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1979.