Heinmot Tooyalakekt (Thunder Rising to Loftier Mountain Heights), also known as Chief Joseph, was a prominent figure among the Nimiipuu, or Nez Perce. He is best remembered as a leader during the Nez Perce War of 1877. Although his role in that conflict is much misunderstood, Joseph participated significantly in events leading up to the war, and his shrewd leadership afterward was critical to the Nez Perces’ successful return from exile to the Pacific Northwest.

Joseph was born in 1840 in the Wallowa Valley of eastern Oregon. His father, Tuekakas, or Old Joseph, was the head chief of the largest of many independent Nez Perce bands living in Oregon, central Idaho, and southeastern Washington. Like many Nez Perces, Joseph had relatives among the Cayuses, Walla-Wallas, Palouses, and other groups of the Columbia River Basin.

In 1871, when Joseph took over leadership of his band upon his father’s death, the Nez Perces were increasingly divided and in crisis. After first welcoming whites to the region in the 1830s—Old Joseph himself briefly converted to Christianity—many Nez Perces had become disillusioned and wary at the flood of settlers into the Oregon Country. Alarm grew in 1855 when Washington’s territorial governor Isaac Stevens pressed on them a treaty, followed by a calamitous gold rush into lands of the Idaho bands in 1860-1861. Most disturbing was a highly suspect treaty in 1863 that demanded the surrender of 90 percent of tribal lands. Joseph’s band, which never agreed to the treaty, was one of several that the federal government ordered to abandon their home country and crowd in with all other bands onto a small reservation.

Many Nez Perces—eventually a majority—moved to the reservation; but a large minority resisted, and Joseph emerged as their leading spokesman. In meetings and councils from 1874 to 1877 with army officers, Indian agents, and a delegation from Washington, D.C., he argued persistently that the resistant Nez Perce bands were not bound by the 1863 treaty. As a follower of the Dreamer religion of the Columbia Plateau, he pleaded as well that his people were intimately bound to their homeland and could never leave it and that to become farmers, as the government insisted, would violate the Earth Mother.

Tall and broad-shouldered with a wide, handsome face, Joseph impressed his white adversaries and managed to forestall a showdown until spring 1877. At a council on May 15, General Oliver O. Howard, commander of U.S. forces in the Pacific Northwest, insisted that all resisting bands report to the reservation within a month. Joseph, seeing no choice, favored compliance.

On the eve of the deadline, however, warriors from other bands killed about eighteen white settlers, and the Nez Perce War began. After fighting for a few weeks in their home country, the Nez Perces fled eastward to Montana, passed through the newly created Yellowstone National Park, and moved northward toward refuge in Canada. They eluded or defeated their pursuers over and over, only to be caught forty miles short of the U.S.-Canada border at the base of the Bear’s Paw Mountains near present-day Chinook, Montana. At that place, Joseph once again spoke for the bands, in a brief speech of surrender C.E.S. Wood recorded that reportedly ended with “From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.”

At that time and afterward, Joseph was called a military genius who had led his people on a remarkable fighting odyssey, but he was never a war leader. He was, rather, a diplomat and a negotiator, and he made his greatest contribution in that role after the war.

Despite a promise that they could return to Idaho, the Nez Perces were sent to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) and told they must remain there. In a visit to the national capital, in presentations in the national press, and in visits with agents and politicians, including President Rutherford Hayes, Joseph played brilliantly on his widely admired image to argue that the Nez Perces had been wronged. Now, accepting defeat, they asked only to return home.

After eight years in exile, the bands were sent back to the Pacific Northwest in 1885. Some returned to the reservation in Idaho, but Joseph and more than half of the rest were sent to the Colville Reservation in north-central Washington Territory. Joseph continued to petition to resettle his people in eastern Oregon. He traveled east several times, meeting with high officials and once riding in the parade at the opening of Grant’s tomb. Nevertheless, except for two brief visits, he was not allowed to return to the Wallowas.

Joseph died in his lodge on the Colville Reservation on September 21, 1904, probably of a heart attack or stroke. His grave, marked by a large monument, is in Nespelem, Washington.

-

![]()

Wallowa Mountains, 1912.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrgLot369_FinleyB0623

-

![]()

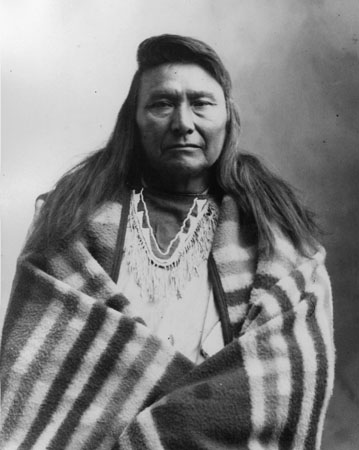

Heinmot Tooyalakekt (Chief Joseph), 1890s..

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 86031

Related Historical Records

Further Reading

Greene, Jerome A. Nez Perce Summer, 1877: The U.S. Army and the Nee-Me-Poo Crisis. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press, 2001.

Josephy, Alvin M. The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin, 1997.

McWhorter, Lucullus V. Yellow Wolf: His Own Story. Caldwell, Id.: Caxton Printers, 1995.

Thompson, Scott M. I Will Tell of My War Story: A Pictorial Account of the Nez Perce War. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000.

West, Elliott. The Last Indian War: The Nez Perce Story. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.