According to our best information, the name "Chinook" (pronounced with "ch" as in church) originated in one Native village on the north bank of the Columbia River, near its mouth. When American and British seafarers came to the Columbia River in 1792, they quickly incorporated the lower river into the international fur trade. They adopted the name "Chinook" early to refer both to the Columbia River and the lower river's Indigenous inhabitants, who for the most part closely resembled the people of Chinook village in appearance, language, and culture.

When referring to the people and their original tribal languages, the name usually appears today as Chinookan. "Chinook" came into early general currency also for a local hybrid language alternatively termed "(the) jargon" (hence, also, Chinook Jargon or, following local Native usage, Chinuk Wawa) that early traders used in preference to Chinookan languages, which were reputedly exceptionally difficult to learn.

Local Natives had more options for communicating with Chinookans, inasmuch as many of the latter also spoke neighboring tribal languages. At the same time, few local non-Chinookan Natives could speak Chinookan. Before English came into general regional currency, Chinook Jargon was the lingua franca of the lower Columbia, linking Natives of different tribes as well as Natives and foreigners.

Scholars have spilled a good deal of ink debating the origin, historical development, and linguistic description of Chinook Jargon. A relatively small but grammatically and semantically central portion of the Chinook Jargon lexicon comes from the Nootkan languages of Vancouver Island, some 200 miles north of the lower Columbia. Linguistic analysis of this part of the lexicon reveals grammatical and phonetic distortions that are consistent with adoption by European-language speakers. This is confirmation that these words were introduced by seafaring traders who had been at Vancouver Island before first entering the Columbia River.

Altogether, the seafarers and English-speaking resident traders and settlers who followed them contributed as much as 20 percent of the Chinook Jargon words used on the lower Columbia during the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Roughly 15 percent of them were derived directly from English and 5 percent from seafarer-pronounced Nootkan.

Yet, it cannot be taken for granted that early foreign traders created Chinook Jargon. While sometimes missing Chinookan grammatical markers, virtually all of Chinook Jargon's Chinookan-contributed words show intact Chinookan word-forms, although whites tended to drop certain features of pronunciation that were retained by Indians.

So far, scholars have been unable to agree on when and how Chinook Jargon originated. Some have argued that it arose as a direct or indirect result of encounters with seafarers. Others believe that it is rooted in Indigenous trade and slavery far predating encounters with non-Natives. What can be said with some certainty is that Chinook Jargon's strongly Chinookan character points to the crucial participation of Chinookans in its formation, whenever that took place. And there is no disagreement that the land-based fur trade in the Columbia River region, commencing with the founding of Astoria in 1811, was key to the dissemination of Chinook Jargon beyond the lower Columbia into the Pacific Northwest at large.

An important role in the development and spread of Chinook Jargon during this period was played by the Métis offspring of local Indian women and fur-company employees. One legacy of those families is the approximately 15 percent of the Chinook Jargon lexicon derived from French, the predominant language of the fur-company rank-and-file.

During its heyday in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Chinook Jargon was spoken throughout the Pacific Northwest, from northern California to the Alaskan panhandle and from the coast well into the interior plateaus of the Fraser and Columbia rivers. During this period, the language acquired an embryonic written literature, composed primarily by missionaries who resorted to it as a way around the diversity and forbidding complexity of Northwest tribal languages.

While long since displaced by English as the region's lingua franca, Chinook Jargon survived for many generations in the Métis and Indian communities of the lower Columbia. For some modern descendants of those communities, it retains positive symbolic associations with Indigenous identity.

Recently, the language has been revived, notably at the Grand Ronde Indian Community, Oregon, where it is taught as a community heritage language.

-

![]()

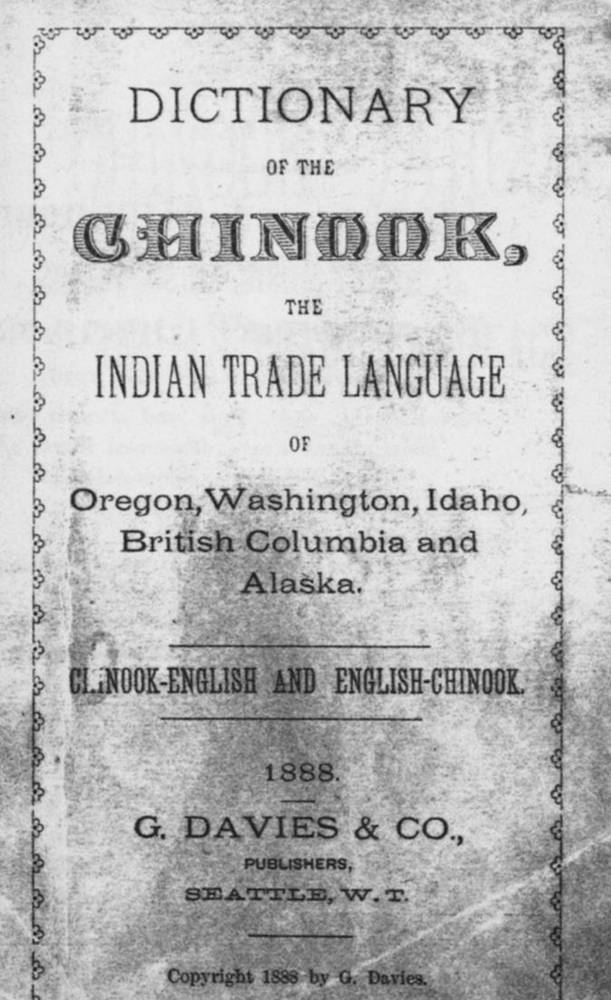

Chinook Jargon dictionary, 1888, title page.

University of Washington Special Collections

-

![]()

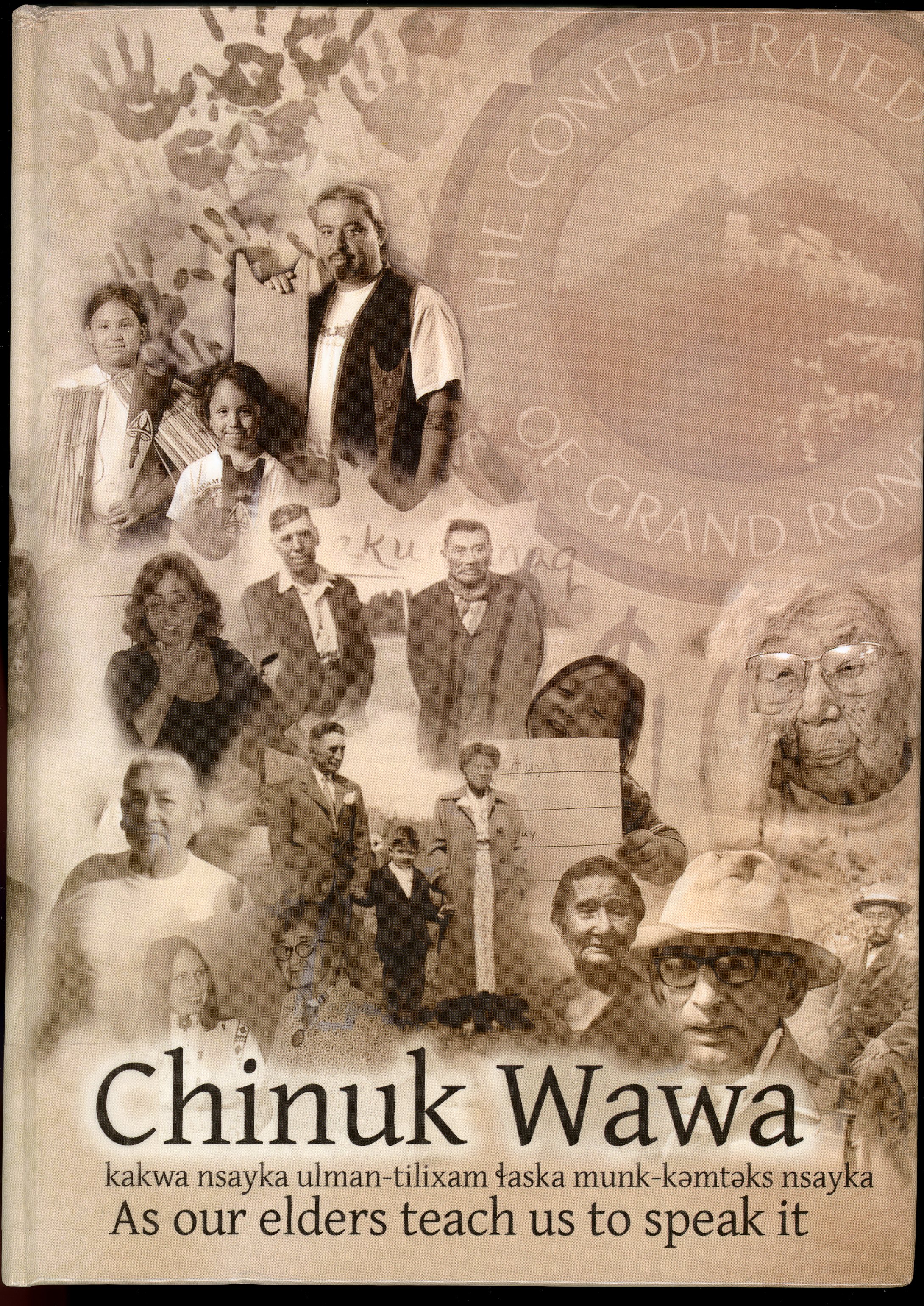

Chinuk Wawa dictionary, published in 2012.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![]()

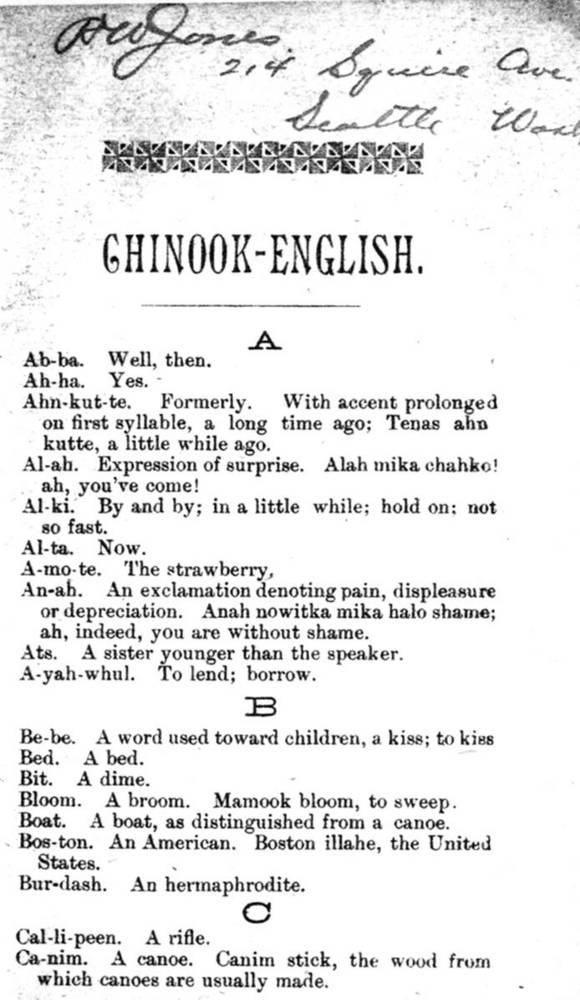

Chinook Jargon dictionary, 1888, p. 7.

University of Washington Special Collections

-

![]()

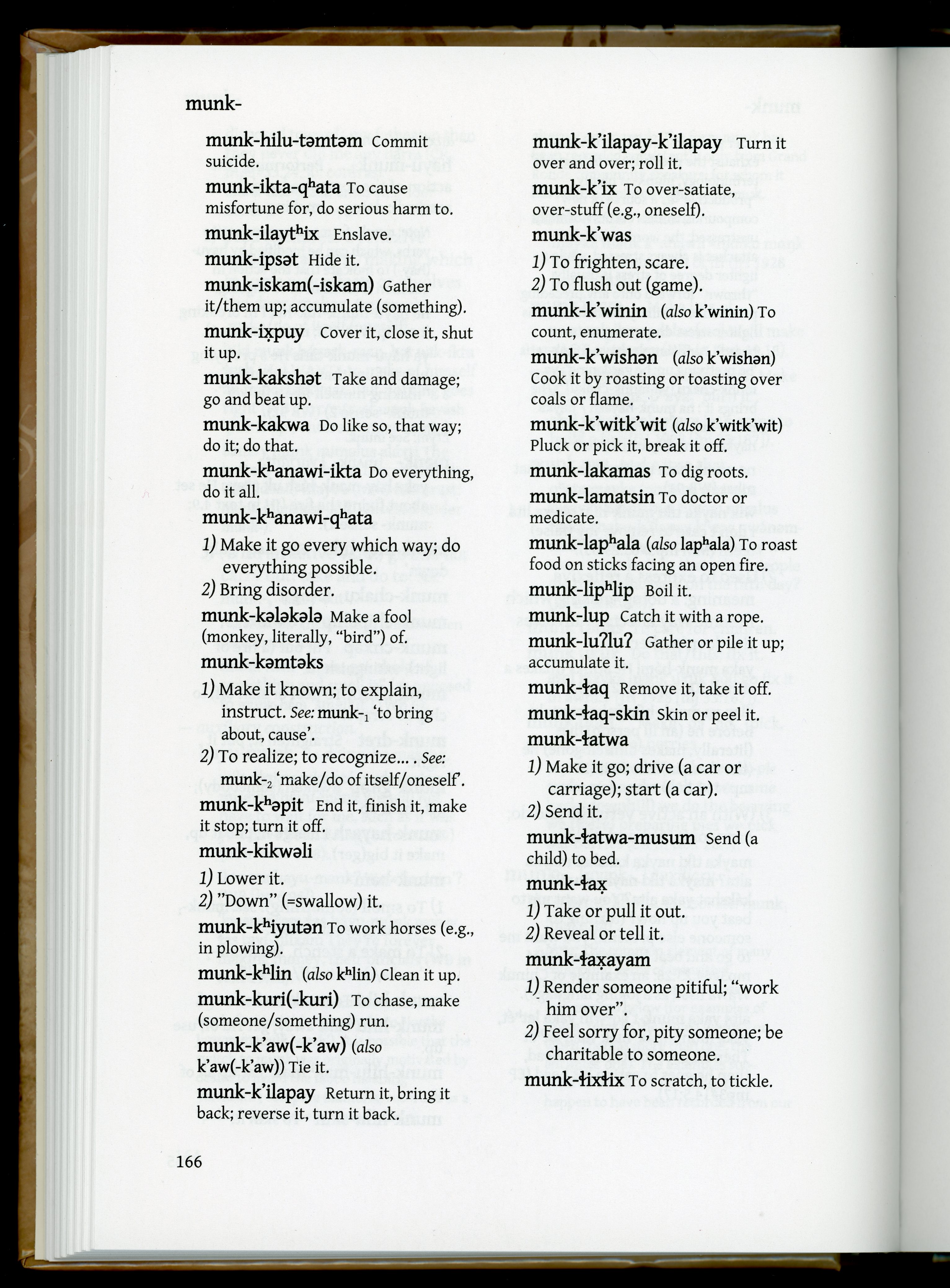

Chinook Jargon dictionary, 1888.

University of Washington Special Collections

-

![]()

A page from the 2012 Chinuk Wawa dictionary.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

Related Entries

-

![Fort George (Fort Astoria)]()

Fort George (Fort Astoria)

Fort George was the British name for Fort Astoria, the fur post establi…

-

![Melville Jacobs (1902-1971)]()

Melville Jacobs (1902-1971)

Melville Jacobs did more to document the languages, cultures, oral trad…

-

![Portland Basin Chinookan Villages in the early 1800s]()

Portland Basin Chinookan Villages in the early 1800s

During the early nineteenth century, upwards of thirty Native American …

-

![Victoria (Wishikin) Wacheno Howard (1867-1930)]()

Victoria (Wishikin) Wacheno Howard (1867-1930)

Victoria (Wishikin) Wacheno Howard was the teller of Clackamas Chinook …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Chinuk Wawa Dictionary Committee. Chinuk Wawa as Our Elders Teach Us to Speak It. Grand Ronde, Oregon: Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde. Distributed by University of Washington Press, Seattle, 2012.

Demers, Modeste, F.N. Blanchet, and L.N. St. Onge. Chinook Dictionary, Catechism, Prayers, and Hymns. Montreal, 1871.

Gibbs, George. A Dictionary of the Chinook Jargon, or Trade Language of Oregon. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1863.

Grant, Anthony. 1996. "Chinook Jargon and Its Distribution in the Pacific Northwest and Beyond." Pp 1185–1208 in Atlas of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas. Stephen Wurm, Peter Muhlausler, and Darrel Tryon, eds. Amsterdam: Mouton DeGruyter.

Lang, George. Making Wawa: the Founding of Chinook Jargon. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2008.

Zenk, Henry, and Tony A. Johnson. "Chinuk Wawa and Its Roots in Chinookan." Pp 272-287 in Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia River. Robert T. Boyd, Kenneth M. Ames, Tony A. Johnson, eds. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013.

http://ikanum.grandronde.org. "Ntsayka Ikanum, Our Story: A virtual experience." Clicking on the Wawa / talk icon accesses text, audio, and video related to Chinuk Wawa (Chinook Jargon) in general and the Chinuk Wawa language program of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde in particular.