Established by Congress in 1986, the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area extends eighty-five miles along both sides of the Columbia River, from the Sandy River to the Deschutes River, and extends between one and four miles from the river in Oregon and Washington.

The legislation provided protection for the scenic and natural resources of the Columbia River Gorge, which is a source of hydroelectric power (from Bonneville and The Dalles dams) and a continental transportation corridor (two major railroads, barge navigation, and Interstate-84). The Scenic Area abuts the Portland-Vancouver metropolitan area and includes long-established towns that developed around agriculture and logging. Approximately 55,000 people lived within the boundaries of the Scenic Area in the early twenty-first century.

With support from Senator Mark Hatfield, the National Scenic Act was most vigorously advocated by Nancy Russell and the Friends of the Columbia Gorge. The motivation of the Friends was to protect scenery and natural systems from Portland-Vancouver suburban sprawl and from scattershot proliferation of second homes. To gain passage, however, the legislation had to acknowledge the importance of preserving a vital Gorge economy.

As a result, the legislation is a balancing act that tries to preserve and enhance natural and scenic values while protecting the livelihoods of residents. Its two goals read as follows:

"(1) Protect and provide for the enhancement of the scenic, cultural, recreational, and natural resources of the Columbia River Gorge.

"(2) Protect and support the economy of the Gorge by encouraging growth to occur in existing urban areas and by allowing future economic development that is consistent with paragraph 1."

The legislation divides the Gorge into three categories: 115,100 acres of Special Management Areas, where little development is allowed (mostly federal land); 149,004 acres of General Management Areas (largely private land); and 28,511 acres in thirteen Urban Areas. Urban Areas are exempt from the legislation, with land-use decisions remaining under local control. The Urban Areas in Oregon are Cascade Locks, Hood River, Mosier, and The Dalles.

Multiple partners manage the scenic area. The U.S. Forest Service has responsibility for the Special Management Areas. Four Native American tribes—the Nez Perce, Yakama, Umatilla, and Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs—have an explicit role in identifying historic and cultural resources. A Columbia River Gorge Commission oversees implementation and has responsibility for the General Management Areas.

The Commission is funded in equal amounts by Oregon and Washington, with three members appointed by the governor of Oregon, three by the governor of Washington, and one by each of the six counties that share the Gorge (three in Oregon and three in Washington). The counties are very diverse. Clark and Multnomah counties are largely metropolitan, with undeveloped eastern edges within the Scenic Area. Hood River and Wasco counties in Oregon have strong agricultural economies and the small cities of Hood River and The Dalles. Skamania and Klickitat counties in Washington have the smallest populations.

The Forest Service and the Gorge Commission worked together to create the Management Plan that was adopted in 1991 and revised in 2004. The plan covers:

(1) land-use designations, using the broad categories of agricultural land, forest land, open space, commercial land, and residential land spelled out in the legislation.

(2) policies for protection and enhancement of scenic, cultural, natural, and recreation resources.

(3) action programs for recreational and economic development, enhancement of Gorge resources, and public education.

(4) administrative roles for the partners in Scenic Area management.

The Management Plan was administered originally by the Forest Service and the Gorge Commission with the expectation that counties would assume implementation within the GMA after adopting suitable ordinances. Five of the six counties did so by the mid-1990s; Klickitat County, Washington, has declined to do so.

The 1986 legislation provided modest appropriations to reduce economic activity in some parts of the Gorge and increase it in others, in effect trying to move employment toward the urban centers. Funds were used for the Skamania Lodge conference center in Stevenson, Washington, the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center in The Dalles, and restoration of segments of the Historic Columbia River Highway for hiking and biking. In contrast, the Forest Service has acquired 31,000 acres of SMA land from willing sellers, reducing the likelihood of recreational development and excessive logging.

Over more than two decades, attitudes toward the Scenic Area have slowly changed. Opinion polls show increasing acceptance of the legislation and its regulations, which now seem a part of the institutional landscape and a tool that Gorge residents can use to help control their own future.

-

![]()

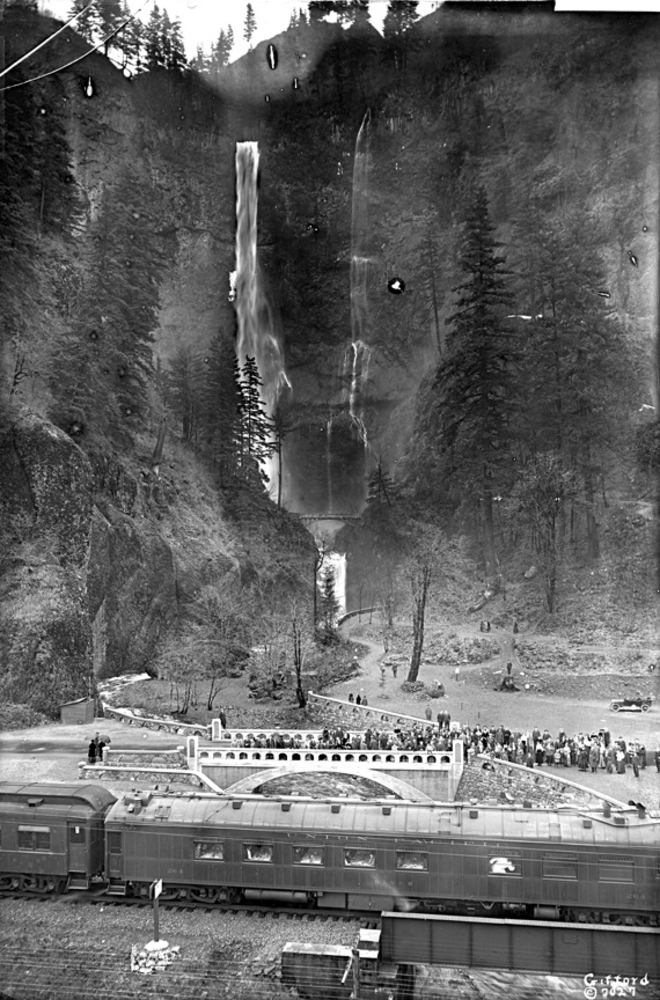

Multnomah Falls.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb003158

-

![]()

Vista House dedication, Columbia River Highway, 1918.

Oreg. Hist. Research Lib., bb000710

-

![]()

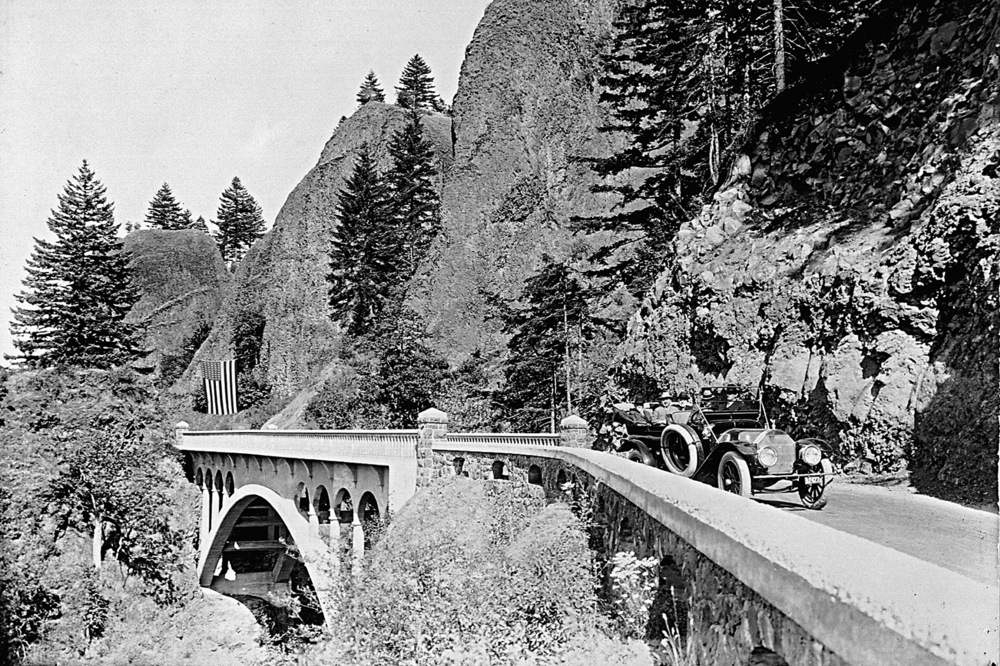

Columbia River Highway near Multnomah Falls, 1915.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

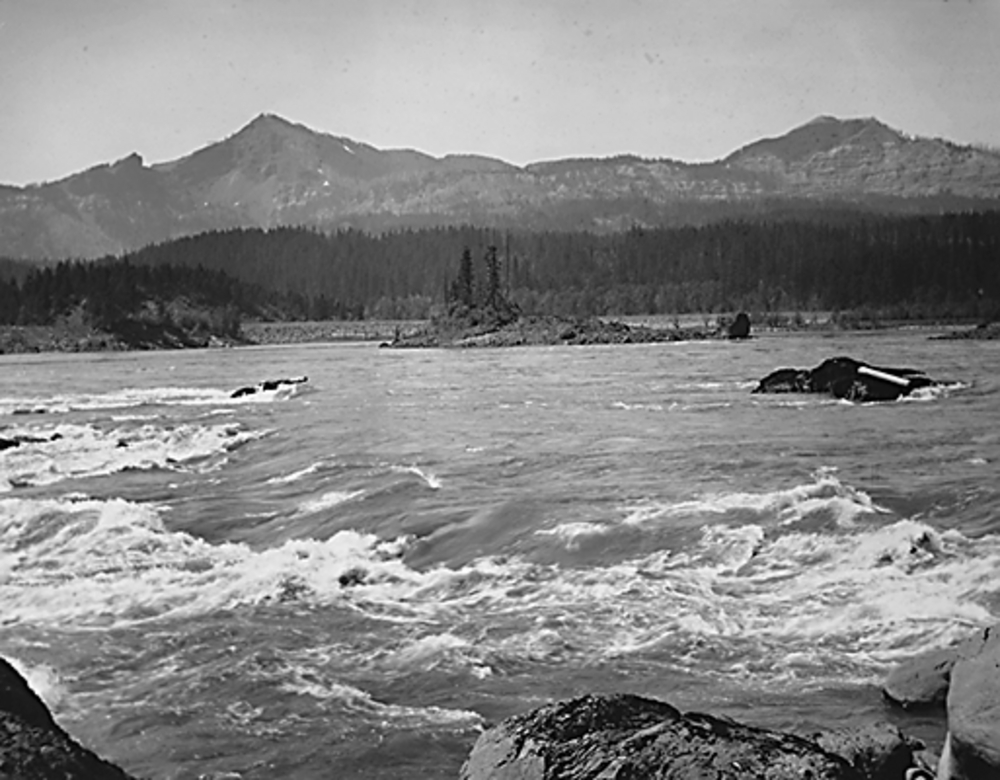

Head of Cascade Rapids, Columbia River.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

Wahkeena Falls.

Wahkeena Falls. Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Orhi37306

-

![]()

Columbia River Highway near Shepard's Dell.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 67636

-

![]()

Bonneville Dam.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 73504

Related Entries

-

![Columbia River]()

Columbia River

The River For more than ten millennia, the Columbia River has been the…

-

Columbia River Highway

The Columbia River Highway, now known as the Historic Columbia River Hi…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Abbott, Carl, Sy Adler, and Margery Post Abbott. Planning a New West: The Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1997.

Bowen Blair, Jr., "The Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area: The Act, Its Genesis, and Legislative History," Environmental Law, 17 (1986-87): 863-969.

Williams, Chuck. Bridge of the Gods, Mountains of Fire: A Return to the Columbia Gorge. New York: Friends of the Earth, 1980.