The Columbia River Highway, now known as the Historic Columbia River Highway, was a technical and civic achievement of its time, successfully mixing ambitious engineering with a sensitivity to the magnificent landscape of the Columbia River Gorge. Entrepreneur and Good Roads promoter Samuel Hill teamed up with engineer and landscape architect Samuel C. Lancaster to create a highway that would make the idyllic natural setting accessible to tourists without unduly marring its beauty. When the first section of road opened in 1915, the Columbia River Highway became the first paved highway in the Pacific Northwest.

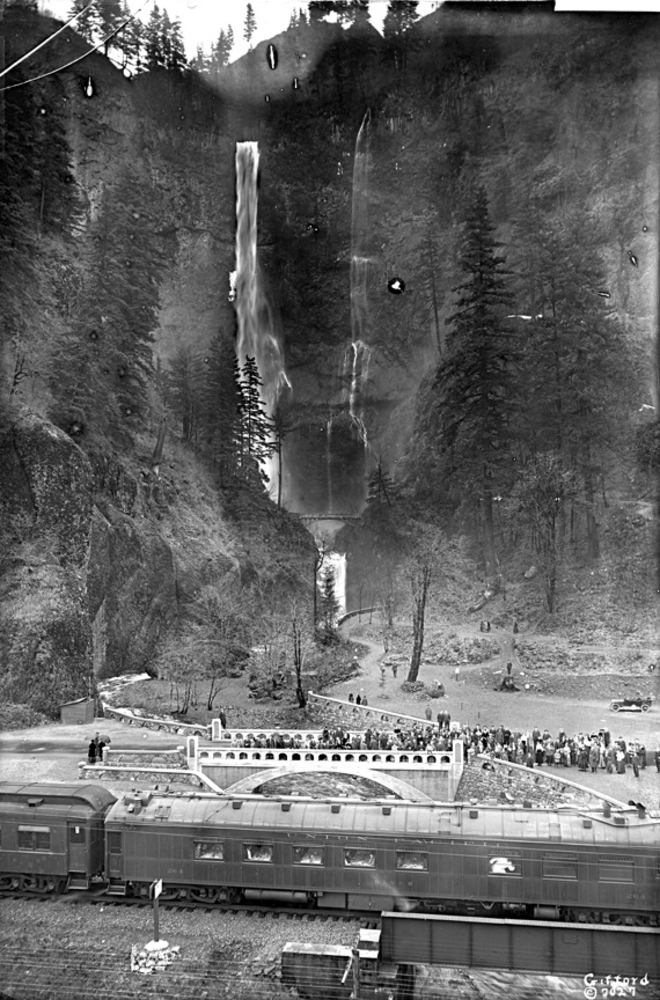

Lancaster was captivated by Multnomah Falls, some thirty miles east of Portland, and his description of the falls seemed to erupt from his heart. "It is pleasing to look upon in every mood," he wrote, "it charms like magic; it woos like an ardent lover; it refreshes the soul; and invites to loftier, purer things." With the Columbia River Highway, Lancaster believed that he was opening up the Columbia Gorge's waterfalls, mountains, and coves for all to enjoy. "If the road is completed according to plans," he predicted, "it will rival if not surpass anything to be found in the civilized world."

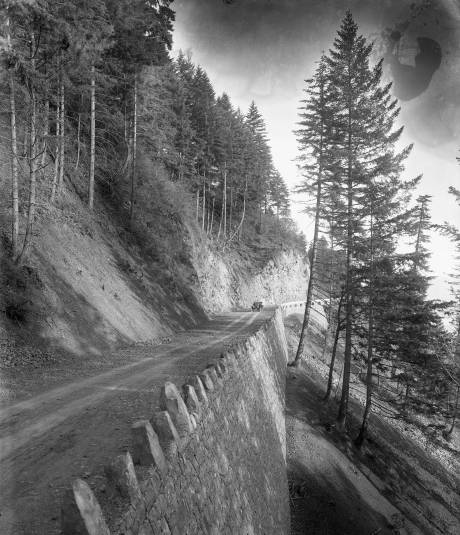

Constructed from 1913 to 1922, the seventy-four-mile Columbia River Highway extended east from the Sandy River near Troutdale to The Dalles. With its pioneering advances in road design, the road is an outstanding example of modern highway development in twentieth-century America. Patterned after the roads of western Europe and the British Isles, the design included the adherence to grade and curve standards, comprehensive curb and drainage systems, dry and mortared masonry walls, reinforced-concrete bridges and tunnels, and asphaltic concrete pavement.

Construction began after Hill and other enthusiasts persuaded the Multnomah County Commission and the state legislature that the route was an important part of a new state highway system. Multnomah County relied on revenue bonds to underwrite the road's construction, and retired lumberman John B. Yeon oversaw construction as Multnomah County Roadmaster. Thereafter, federal highway funds and Oregon fuel-tax proceeds helped finance the work in Hood River and Wasco counties. Ultimately, the road through the Gorge became part of a longer Columbia River Highway that stretched from the Oregon Coast to Pendleton, where it connected with the Old Oregon Trail Highway.

Retired lumberman and hotelier Simon Benson purchased many scenic spots along the highway alignment, including Multnomah Falls, and donated them back to the state to preserve them for future generations.

By the 1930s, Lancaster's "King of Roads" had difficulty meeting increasing traffic demands, and engineers designed a new, curvilinear water-level route to bypass much of the old highway. Two lanes were completed to The Dalles by 1953. The designers preserved the highway's western segment, from the Sandy River to Ainsworth, so visitors could reach waterfalls, hiking trail, and scenic vistas, and an eastern segment from Mosier to The Dalles through orchard and plateau country. Although the designers were not able to save major portions of the old highway from Cascade Locks to Hood River, they were able to preserve its views. By 1970, two additional lanes and interchanges transformed the new route into a modern freeway, initially designated as Interstate 80N and later renamed Interstate 84.

In 1981, prompted by private citizens and local, state, and federal agencies, the National Park Service brought together a group of professionals to study the Columbia River Highway. They produced two important documents that offered guidance for the road's maintenance, conservation, and reuse. A year later, destruction of the highway's Hood River Bridge sparked a groundswell of support for saving the rest of the route for future generations.

In 1983, the road and associated designed landscapes were listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Oregon's Department of Transportation took an active role in preserving and restoring the highway's historic features, and the major drivable portions received much-needed repair. Many abandoned segments were reopened for bicycle and pedestrian use as the Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail. The capstone of this effort was the rehabilitation of the Mosier Twin Tunnels and the 4.5-mile segment between Hood River and Mosier.

In 1984, the American Society of Civil Engineers designated the highway a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark. The highway became a National Scenic Byway-All American Road in 1999. A year later, much of the road and trail segments received its highest acclaim—designation as a National Historic Landmark, which recognized the highway as a significant national heritage resource. The designation recognized how, a decade after the initial completion of the highway, the National Park Service made Lancaster's design standards the cornerstone of its "Lying Lightly on the Land" philosophy for future national park roads and trails.

-

Columbia River Highway near Multnomah Falls, 1915.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb000775

-

Samuel Lancaster and friends on the Columbia River Highway, about 1916..

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 67636

-

![]()

Road workers protest on Columbia River Highway, April 25, 1914.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 38744

-

![]()

Oneonta Gorge bridge construction, Columbia River Highway, 1948.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 094334

-

![]()

Columbia River Highway embankment on, 1915.

Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Gifford Photo. Collec., P218:BAG

-

![]()

Columbia River Highway in winter, 1916.

Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Gerald W. Williams Collec., Columbia R. album, WilliamsG_CR_highway winter

-

![]()

Mitchell Point Tunnel, Columbia River Highway.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb000005

-

![]()

Vista House dedication, Columbia River Gorge, May 1918.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb000710

Related Entries

-

![Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area]()

Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area

Established by Congress in 1986, the Columbia River Gorge National Scen…

-

Samuel Magnus Hill (1851-1921)

Samuel Magnus Hill came to Oregon in 1915 as minister of the Swedish Ca…

-

![Simon Benson (1851-1942)]()

Simon Benson (1851-1942)

Simon Benson gave his name to a Portland high school, a Portland hotel,…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Fahl, Ronald J. “S. C. Lancaster and the Columbia River Highway: Engineer as Conservationist." Oregon Historical Quarterly 74:2 (June 1973): 101-44.

Hadlow, Robert W. “Columbia River Highway Historic District, National Historic Landmark Nomination." Portland: Oregon Department of Transportation, 2000.

Hadlow, Robert W. “The Columbia River Highway: America's First Scenic Road." Journal of the Society for Commercial Archeology 18:1 (Spring 2000): 14-25.