The high-voltage power lines that march across central Oregon, linking Columbia River dams to Los Angeles, California, are “proof of the power of cooperation and unity” between the United States and Canada, President Lyndon Johnson declared on September 17, 1964. The president was speaking at the Intertie Victory Breakfast in Portland, one day after he and Canadian Prime Minister Lester Pearson met at the Washington-British Columbia border to proclaim the Columbia River Treaty. Importantly, he presented a check to Canada for nearly $254 million to help pay for the construction of three large water-storage dams in British Columbia. It was the final step in creating a treaty that would bring economic benefits to both countries. With this payment, construction could get under way.

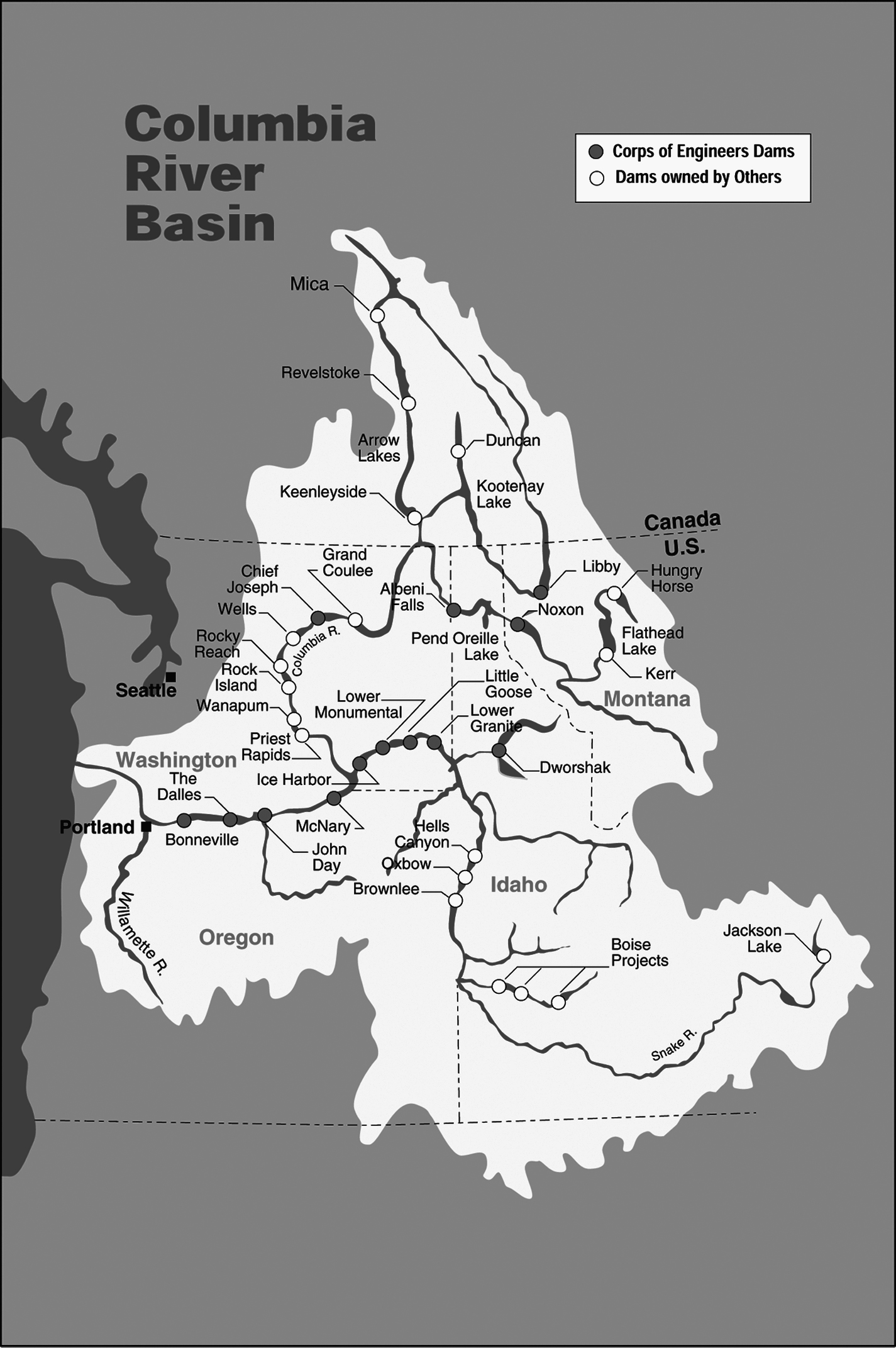

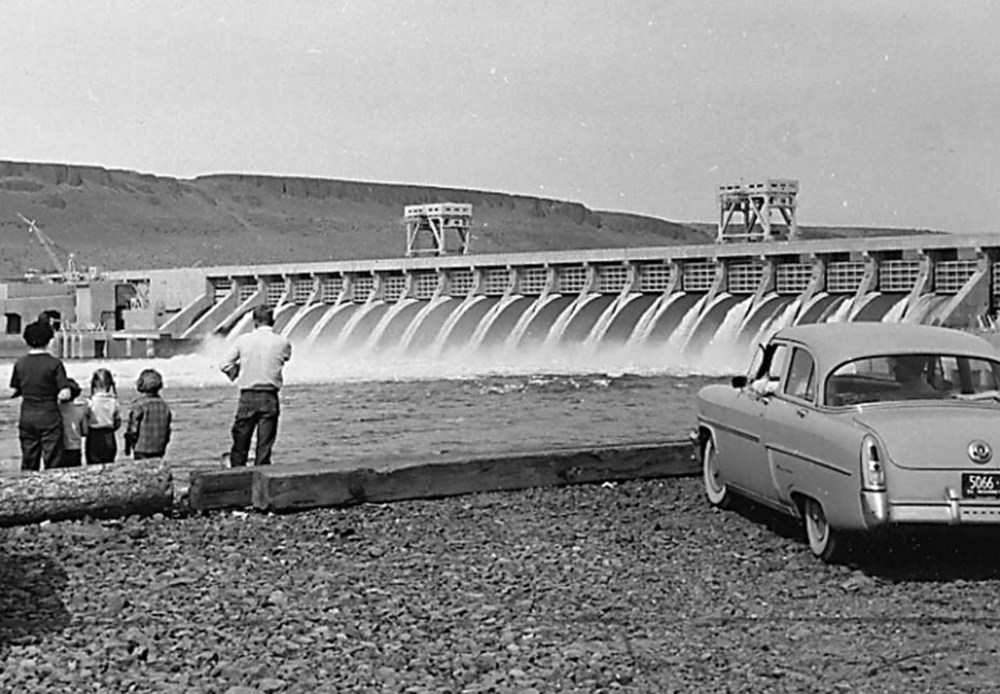

In the 1964 Columbia River Treaty, Canada and the United States recognized the great value of the river to both countries. The river begins in British Columbia. By building three water-storage dams there, water in the upper reaches of the river could be released with precision to flow into the United States, augmenting natural flows. This would have benefits for both countries: better flood control and more hydropower generation. River communities from Trail to Portland would benefit from better flood control, and both countries would share equally in the revenue from the additional electricity generated at the eleven mainstem Columbia River dams in the United States.

In short, the treaty was an exercise in economic development of a shared resource, a natural evolution of generations of friendship between the two countries. The preamble notes that Canadian and American citizens “have, for many generations, lived together and cooperated with one another in many aspects of their national enterprises for the greater wealth and happiness of their respective nations.”

The treaty dams are Duncan (1967), on the Duncan River, and Keenleyside (1968) and Mica (1973), both on the Columbia. Collectively, the three dams provide a total of 15.5 million acre-feet of water storage. The treaty also authorized Libby Dam, on the Kootenai River in Montana, for flood control and other purposes; Canada agreed that the reservoir behind Libby Dam (1972) could back forty-two miles into British Columbia. The Pacific Northwest-Pacific Southwest Intertie was not part of the treaty, but it is a direct result and allows both nations to realize the benefits of the treaty. Congress authorized construction of the Intertie in 1964; the first lines were completed in 1970.

The groundwork of the treaty began in March 1944, when the United States and Canada asked the International Joint Commission to investigate “whether a greater use than is now being made of the waters of the Columbia River System would be feasible and advantageous.” The commission appointed a board to investigate. Its report, completed in April 1959, analyzed power-generation and flood-control alternatives. In response to questions from the two governments, the commission issued a set of principles to apply in determining the benefits to each country from cooperative water storage, flood control, and power generation.

After nine diplomatic negotiating sessions, the treaty was signed in January 1961 and implemented on September 16, 1964, when President Johnson and Prime Minister Lester Pearson signed documents at Blaine, Washington, near the Canada-U.S. border.

The treaty addresses only flood control and hydropower and has no expiration date. It will continue indefinitely unless one country requests termination, which is allowed any time after 2024, with at least ten years advance notice—that is, the first opportunity to request termination was in 2014. Neither country has made a request.

Under the treaty, Canada receives half of the increased downstream hydropower production. This is known as the Canadian Entitlement. In 1964, British Columbia did not need the additional power and so sold it to the Columbia Storage Power Exchange, a consortium of utilities in the United States, for thirty years for $253.93 million (in U.S. dollars). That amount, plus payments for flood control, mostly paid for the three Canadian dams.

In April 1998, the countries agreed on new terms for the continued return of the Canadian Entitlement, this time as power rather than cash. The countries also agreed that BC Hydro, the largest electricity utility in the province and the official Canadian “entity” under the treaty, could market its share of the energy in the United States. The Canadian Entitlement varies from year to year and is calculated in advance for planning purposes. The 2018-2019 operating year amount is 1,284 megawatts of capacity and 472.5 average-megawatts of energy, roughly similar to previous years and equivalent to the average annual power demand of about 341,000 Northwest homes.

In his Portland speech in 1964, President Johnson lauded not only the international cooperation that led to the treaty, but also the collaboration of public and private utilities in the three Pacific states for brokering the Intertie, which Johnson called “the most exciting transmission system in history.” Senator Wayne Morse, who introduced Johnson at the breakfast, was a treaty supporter and had urged the Senate to adopt it. The treaty would, he predicted, “provide the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia with a major block of low-cost power—at minimum expense and maximum speed.”

In 2010, both countries began thinking about the future of the treaty in anticipation of the 2014 deadline. The Columbia is a different river today than it was in 1964, doing work not addressed in the treaty, such as providing court-ordered flows for the benefit of endangered and threatened species of fish and helping to backstop the variable output of thousands of wind-power turbines in the Northwest. The treaty entities—BC Hydro, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the Bonneville Power Administration—were studying how these requirements would be met while continuing to honor commitments to flood control, hydropower generation, and shared economic benefits.

As the range of Columbia River uses has expanded, so has the number of stakeholders who have an interest in the future of the river—fish and wildlife agencies, Indian tribes, and irrigators, to name a few, in addition to electric utilities, dam operators, and governments. In 2011-2013, the U.S. and Canadian entities conducted studies, addressed the various issues at stake, and formulated recommendations to submit to their respective national governments.

In December 2013, the U.S. Entity released its recommendation after extensive consultations with state and tribal governments and public meetings with various stakeholders. The U.S. position recognizes “an opportunity for inclusion of certain additional ecosystem operations” in a revised or “modernized” treaty, as it is called in the recommendation. Flexibility in the existing treaty has been used to release water for ecosystem benefits, for example, even though those specific benefits are not an authorized purpose of the existing treaty. The U.S. recommendation also notes that “an imbalance has developed in the equitable sharing of the downstream power benefits resulting from the Treaty,” and seeks to correct that imbalance. The recommendation also emphasizes the importance of flood risk management, “a vitally important aspect of coordinated operations with Canada.”

In March 2014, the Province of British Columbia released its recommendation, based on a draft produced by the Canadian Entity in late 2013. The Province asserted that the treaty should continue but should be improved – importantly, within the existing treaty framework. The Canadian position is that the primary objective of the treaty should be to maximize benefits to both countries through the coordination of planning and operations and to compensate for benefit imbalances. All downstream benefits to the United States, such as flood risk management, hydropower, ecosystems, water supply (including municipal, industrial and agricultural uses), recreation, navigation, and any other relevant benefits, should be accounted for and the value shared equitably between the two countries.

Formal negotiations began in 2018, with the first session in Washington, D.C. in May and the second in Nelson, BC, in August. A third session is planned in early 2019. Additionally, the State Department and the Province of British Columbia are conducting public meetings to inform citizens of progress and gather comments.

-

![Columbia River Basin]()

Columbia River Basin.

Columbia River Basin Courtesy U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Related Entries

-

![Bonneville Power Administration]()

Bonneville Power Administration

In 1937, the impending completion of Bonneville Dam (1938) and progress…

-

![Columbia River]()

Columbia River

The River For more than ten millennia, the Columbia River has been the…

-

![U.S. Army Corps of Engineers]()

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, a hybrid military and civilian federa…

-

![Wayne Morse (1900-1974)]()

Wayne Morse (1900-1974)

Wayne Morse and the Vietnam War: the name and the conflict will be fore…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

"Utilities Support Coulmbia River Treaty." The Spokesman-Review, March 9, 1961, p. 16.

Bankes, Nigel. The Columbia Basin and the Columbia River Treaty: Canadian Perspectives in the 1990s. Research Publication PO95-4. Portland, Ore.: Northwest Water Law & Policy Project, Northwestern School of Law, Lewis and Clark College, 1996.

Krutilla, John V. The Columbia River Treaty: The Economics of an International River Basin Development. Baltimore, Md.: Resources for the Future, Inc., 1967.

Northwest Power and Conservation Council. "Columbia River Treaty." http://www.nwcouncil.org/history/ColumbiaRiverTreaty.asp

Pitzer, Paul. Grand Coulee: Harnessing a Dream. Pullman: Washington State University Press, 1994.

Columbia River Treaty. U.S. Department of State.

B.C. Decision, Columbia River Treaty Review, Decision and Guiding Principles, March 2014: https://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/6/2012/03/BC_Decision_on_Columbia_River_Treaty.pdf

United States and Canadian Entities for the Columbia River Treaty, Determination of downstream power benefits for the Assured Operating Plan for Operating Year 2017-18, April 12, 2013, Page 4: http://www.nwd-wc.usace.army.mil/PB/PEB_08/docs/aop/18AOPddpb.pdf