While there have been scores of industrial settlements and communities in Oregon, there have been few planned company towns. By conventional definition, company towns are industrial communities, usually self-contained, in which the company owns and maintains the land, production facilities, and buildings, including shops, stores, schools, and workers’ homes. Dating back to communities such as Lowell, Massachusetts, founded in 1822, such towns have been viewed as paternalistic and symbolic of the exploitation and control of workers. In some cases, however, especially in Oregon, company towns were necessary in remote areas and were managed to increase workers’ well-being rather than to exploit them.

Oregon industrial communities ranged from mining and logging camps, which had little more than communal dining halls and sleeping quarters (sometimes tents), to preplanned settlements based on designs by professional planners and architects, built mostly for workers in timber felling and the lumber industry. In those towns, workers were provided houses, shops and stores, churches, entertainment and recreational facilities, and schools staffed by professional teachers.

Nearly all of Oregon’s company towns, which once numbered more than thirty-five, were created for logging or lumber production. While such towns were located in every quarter of the state, most were east of the Cascade Mountains. Many are now gone, erased from the landscape as the buildings were removed or razed and as the sites were turned into other uses. Such was the fate of Valsetz (Polk County) and Wendling (Lane County), which were replanted as Douglas-fir tree farms (a large concrete block, the remains of the Booth-Kelly company vault, survives in the woods at Wendling).

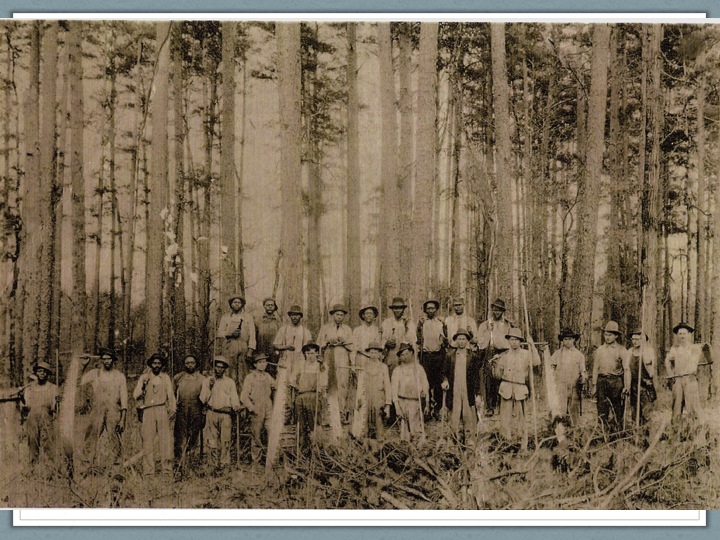

Most of the planned logging communities in Oregon were created in the early decades of the twentieth century, once the forests adjacent to bodies of water or near towns had been cut over. These later towns depended on the railroad to bring logs out of the forest, to ship the raw lumber, and to bring in supplies. Shevlin, built by the Shevlin-Hixon Company, had the distinction of existing sequentially in at least three geographic locations in Deschutes and Klamath Counties. The town’s buildings, schools, and workers’ houses were all specifically designed to be lifted by crane and placed on railroad flatcars, so that when the forest was depleted the entire town could be moved to uncut stands. Much the same was true of the moveable lumber town of Maxville in Wallowa County, owned by the Bowman-Hicks Lumber Company. Both Shevlin and Maxville are now little more than memories for surviving employees.

In a few instances, company owners who believed that worker productivity and morale were positively affected by their surroundings, hired professionals to lay out and build their towns. Prominent San Francisco architect Bernard Maybeck, for example, was engaged as the architect and planner for Brookings. Begun in 1913 by the California and Oregon Lumber Company, a redwood lumber business based in Oakland, California, and owned by J.L Brookings, the town on the southern Oregon coast was built on a plateau above the Chetco River and the Pacific Ocean. Because of the location’s pronounced isolation and in an effort to attract and retain workers, Brookings’s brother Robert urged careful planning to entice and retain workers and their families.

Maybeck devised a unifying architectural theme and adapted the town’s street plan to the rolling topography of the site, laying out winding streets that focused on a town center but reserving the steeper terrain for parks. Employing a kind of Craftsman Shingle Style for the limited number of buildings that were completed—a village store, a hotel, and a few residences—Maybeck aimed at establishing a local stylistic character. Drawings preserved in the town's archives and in the Maybeck papers at the University of California-Berkeley show a number of studies for street and park plans, as well as architectural studies for some fifteen prototypes for low-cost workers' houses, a workers' hostel, a community hall, a bank, a school, and a YMCA.

After the Brookings mill closed in 1925, the population of the town plummeted from 1,000 to perhaps 250 people. The subsequent construction of the Roosevelt Highway (State Highway 101) in the late 1920s was rammed through Brookings, and though the highway connected the town to the outside world, it vitiated Maybeck’s plan. Today, there is scant visual evidence that a major West Coast architect had anything to do with the town that has grown to over 6,000 people. Local planning and building efforts are attempting to return to Maybeck's intentions.

In eastern Oregon, the Edward Hines Lumber Company was major player in developing lumbering in the twentieth century. The Midwest company expanded its operations into Oregon in the late 1920s and by mid-century had acquired a number of timber holdings as well as several established Oregon lumber towns, including Seneca, Dee (Hood River County), and Westfir (Lane County). The company town of Hines in Harney County began with an aborted sale of U.S. Forest Service land to Fred Herrick, contingent on Herrick building a fifty-mile rail line from Burns to Seneca. In 1928, with Herrick’s forfeiture of the land, the Forest Service resold the timber to the Edward Hines Lumber Company, which began building a mill and a town.

The planner and development firm of Stafford, Derbes & Roy was hired to create the new community of Hines, acquiring 2,000 acres to prevent opportunistic building by private speculators. The town took the shape of a large oval, bisected by U.S. 20 and a major cross street, with the high school placed at the northern terminus of the cross street. The innermost central four quadrants were set aside for parkland, to be surrounded by the major public and commercial buildings facing inward on Circle Drive.

An initial 150 residences were designed, reportedly with the assistance of Hines's wife Loretta, who insisted that 68 individual house plans be created to avoid “cookie cutter” monotony. South of the town center was the Hines mill itself, which boasted a huge timber-framed enclosed workroom more than 2,300 feet long. Facing U.S. 20 at the southern end of the mill complex is the Georgian Colonial-style administration building. Once the Depression hit, construction on the concrete-framed Ponderosa Hotel halted, and the unfinished and mostly empty concrete building remains a striking feature of Hines.

Arguably the best designed and operated company mill town, and also the last to be created, was Gilchrist in the Deschutes National Forest. The new mill in northern Klamath County was distant from any local town capable of supplying workers’ needs, so the Gilchrist Timber Company created a self-sustaining community with schools, a movie theater, and shops. Construction of the town, begun in April 1938, was based on Portland architect Hollis Johnston’s plan, with the mill on the west side of Highway 97 and the school and residential, shopping, and entertainment areas on the east side. Johnston used a kind of schematized Scandinavian style for the public buildings, with carefully selected decorative details for the residences.

Company paternalism in Gilchrist was lightly exercised, but its role as something of a benign caretaker ended as the twentieth century drew to a close, when the mill was sold in 1991 and the houses later sold to Gilchrest residents. Company towns in Oregon, as a type, ended with the sale of Gilchrist, for an extended period Oregon's best and most enlightened example of a company town.

-

![Wendling, Oregon]()

Wendling, Oregon.

Wendling, Oregon Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib. neg35978

-

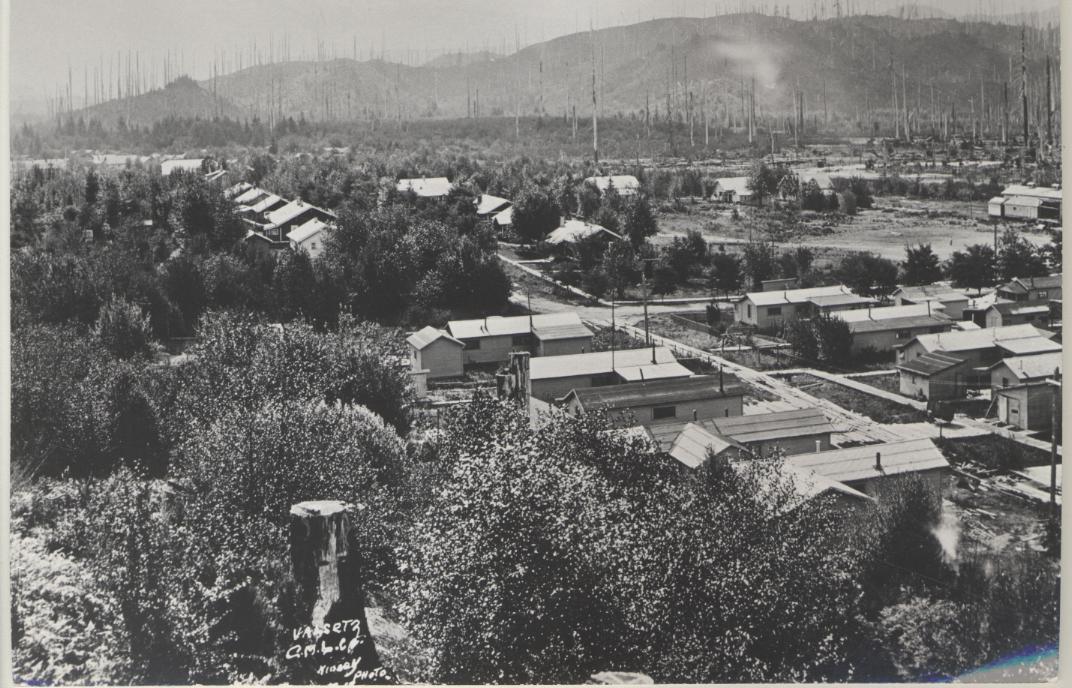

![Cobbs and Mitchell Lumber, Valsetz, 1928]()

Cobbs and Mitchell Lumber, Valsetz, 1928.

Cobbs and Mitchell Lumber, Valsetz, 1928 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., neg50603

-

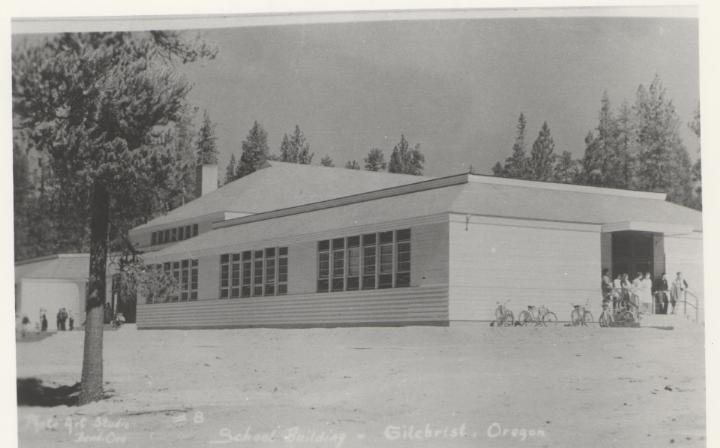

![Gilchrist school, c. 1940]()

Gilchrist school, c. 1940.

Gilchrist school, c. 1940 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib. Orhi85114

-

![Valsetz, Oregon]()

Valsetz, Oregon.

Valsetz, Oregon Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib. neg50604

Related Entries

-

![Brookings]()

Brookings

Brookings is located at the mouth of the Chetco River, on the southern-…

-

![Gilchrist]()

Gilchrist

Gilchrist, in northern Klamath County, located along U.S. Highway 97 ab…

-

Hines and the Edward Hines Lumber Company

In the mid-1920s, large sawmill owners in the United States found a new…

-

![Maxville]()

Maxville

Maxville, in northeast Oregon east of the town of Wallowa, was home to …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Carlson, Linda. Company Towns of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003.

Driscoll, John. "Gilchrist, Oregon, A Company Town." Oregon Historical Quarterly 85 (Summer 1984): 135-53.

Roth, Leland. “Company Towns in the Western United States.” In John Garner, ed., The Company Town: Architecture and Society in the Early Industrial Age, 173-205. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.