On January 5, 1945, the State of Oregon executed Robert Folkes, a twenty-one-year-old Black railroad worker and labor unionist. His arrest, trial, imprisonment, and futile appeals to the Oregon Supreme Court, Oregon Governor Earl Snell, and the U.S. Supreme Court alarmed civil rights activists and opponents of capital punishment for several reasons: Folkes’s age; clear evidence of police misconduct; and the lack of physical evidence or eyewitness testimony linking him with the crime.

Robert E. Lee Folkes was born in the Delta region of Arkansas, the eldest of three siblings who lived with his mother Clara Folkes, a seamstress. According to employment documents, Folkes was born on June 20, 1922, although there is no official record confirming that date. His father, Robert Folkes, had died shortly after white militiamen had violently crushed the Delta’s postwar sharecroppers’ movement. Sharecroppers had organized the Progressive Household and Farmers Union of America and demanded that landlords pay them a fair share of the 1919 harvest, one of the largest in history. Landlords responded by mobilizing nearly fifteen hundred men, who killed nearly 900 Black men and brutalized another 4,500 people. During the chaotic aftermath of the attack, Clara was widowed and fled. She ultimately settled in South Central Los Angeles, an interracial community where Robert attended integrated schools until he was sixteen.

Robert Folkes took a job as fourth cook with the Dining Car Division of the Southern Pacific Railroad (SPR). By 1942, he had been promoted to second cook, a prestigious position usually assigned to older workers, and he spent a few hours each week on regular layovers in Portland, between trains to and from Los Angeles. With his wages, he supported Clara, two siblings, and his common-law wife, Jesse Wilson.

When dining car workers forced the Southern Pacific into collective bargaining in 1942, railroad security forces surveilled and intimidated them. One of the victims of that intimidation was Folkes, a union member whose family was connected to William Pollard, a leader of the effort to organize dining car workers.

At about 4:30 on the morning of January 23, 1943, near Tangent, Oregon, trainmen and passengers in Pullman Tourist Car D discovered a woman slumped in the aisle, her throat cut. U.S. Marine Harold Wilson stood over her, his hands bloody. Claiming that a “dark” man had fled the scene moments before, Wilson gave chase toward the rear of the train, running past the kitchen where Folkes worked. Between Eugene and Klamath Falls, detectives questioned passengers and crew but found no murder weapon and no physical evidence that linked anyone to the murder. No one admitted witnessing the crime, and no one claimed that Folkes was the murderer.

Witnesses claimed to have seen Wilson repeatedly climbing in and out of his bunk, directly above the victim's, behaving suspiciously before and after the murder. Folkes was the nearest Black man, however. District Attorney L. Orth Sisemore delayed the train in Klamath Falls, where he interrogated Black trainmen. The conductor asserted that Folkes could not have killed the woman, given the layout of the diner, the cook’s workload, and conditions in Car D. He suspected the Marine, whose berth (Upper 13) was immediately above the murdered woman’s (Lower 13). Wilson and a Black waiter, John Funches, were detained.

Between Klamath Falls and Dunsmuir, in northern California, Southern Pacific detectives stripped Folkes naked, shoved him into a men’s lavatory, and browbeat him all night, releasing him only for duty shifts. He was sleep deprived and disoriented when LAPD detectives grabbed him off the train in Los Angeles and shuttled him between Central Jail and Police Headquarters for another twelve hours of interrogation, with no lawyers present. They then telephoned Linn County District Attorney Harlow Weinrick, claiming that Folkes had “cracked.”

The case hinged on the “confessions” that Los Angeles Police Department detectives claimed Folkes made. Although a minor, Folkes was extradited to Oregon, where he was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death—all within three months. At trial, Weinrick introduced the so-called confessions. Folkes had denied his guilt in all statements that he acknowledged having made on the train ride south to Los Angeles and in one statement he supposedly made in LAPD custody. But in a second statement in Los Angeles, police said, he had “confessed,” although he was never given the opportunity to review that statement and never acknowledged having made it.

A third statement produced in Albany by an Oregon State Police investigator was similarly suspect. State police officers and sheriff’s deputies at Eugene had intercepted the train returning Folkes to Oregon and took him into custody in the early evening hours, warning him that a “lynch mob” awaited him in Albany. Shoving him into the back seat of a car between two lawmen, they took back roads through Brownsville, Sweet Home, and Lebanon before delivering him to the Linn County jail. OSP Medical Examiner John Beeman interrogated him, again without counsel, and drafted a disjointed, contradictory, sixteen-page “statement” that was presented in court as Folkes’s “confession.” Folkes neither reviewed nor signed any of the supposed statements and denied having made them, but Circuit Judge John Lewelling allowed prosecutors to read them to the jury and provide them with written copies.

The jury deliberated for seventeen hours. Judge Lewelling refused the initial reports of a hung jury and required the eight women and four men to sleep on wooden floors in an empty courtroom. They returned a guilty verdict the next morning. On appeal, the Oregon Supreme Court returned a five-to-two decision upholding the death sentence. The two dissenting justices questioned the integrity of interrogating officers; and Justice George Rossman, an expert on criminal procedure, argued that the “statements” contradicted sworn testimony from officers involved and should not have been allowed into evidence.

The Portland NAACP circulated Rossman’s dissent in petitioning campaigns demanding Governor Earl Snell extend clemency. William McClendon, a civil rights activist and journalist, devoted the first issue of the People’s Observer to Folkes, linking the case with antilabor repression and racism in Oregon’s wartime industries. He inspired a coalition of church members, clergymen, the Urban League, dining car workers’ unions, and the NAACP to try to save Folkes, attracting national support and rekindling opposition to the death penalty in Oregon. A counter-campaign, with connections to the Masonic Order and other fraternal organizations—the victim's father was the Worshipful Master of Masonic Lodge 1 who appealed to the former governor of Virginia, a fellow lodge member, to ask Oregon Governor Snell, also a Mason, to intervene in the case and ensure a conviction—demanded that the sentence be carried out. The appeal to the Supreme Court was refused, and Snell refused to intervene.

On January 5, 1945, Folkes became the second Black man executed by the State of Oregon.

-

![]()

Robert Folkes, Linn County Courthouse, 1943.

Courtesy California State Railroad Museum

-

![]()

Car "D," Klamath Falls, 1943.

Courtesy California State Railroad Museum

-

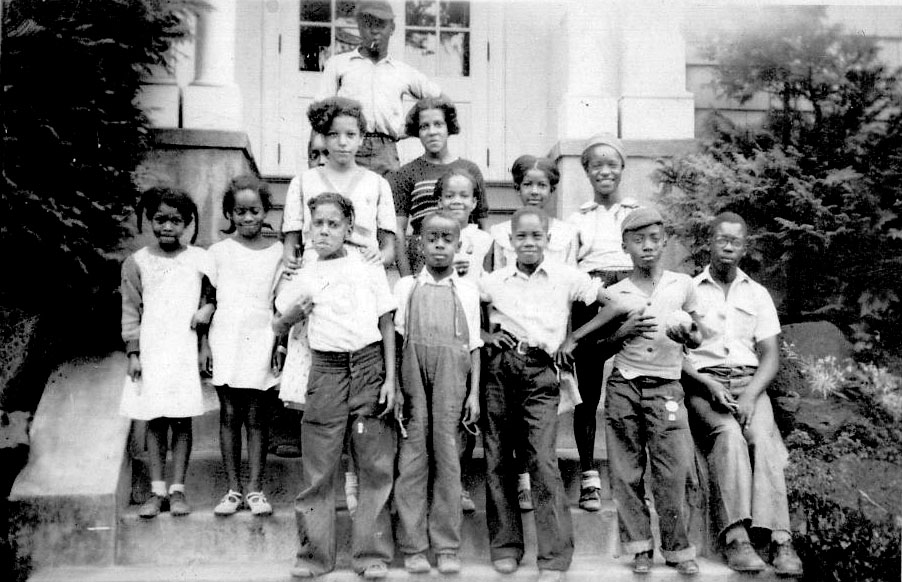

![From left to right: Solomon Studyway, John Funches, and Jessie Hall. All were exonerated.]()

Dr. George Adler collects samples from Black railroad employees, 1943, Klamath County.

From left to right: Solomon Studyway, John Funches, and Jessie Hall. All were exonerated. Courtesy California State Railroad Museum

Related Entries

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![Earl Wilcox Snell (1895–1947)]()

Earl Wilcox Snell (1895–1947)

Earl Snell was a Republican governor of Oregon who served during World …

-

![William McClendon (1915-1996)]()

William McClendon (1915-1996)

William McClendon was a writer, journalist, intellectual, activist, and…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Geier, Max G. The Color of Night: Race, Railroaders, and Murder in the Wartime West. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2015.

State of Oregon v. Robert E. Lee Folkes, Transcript of Testimony, OSSC Case Files, Case No 14865, Drawer No 9449, Oregon State Archives.

Barker, Neil. "Murder on Train Number 15." Oregon Historical Quarterly (Fall 2011).