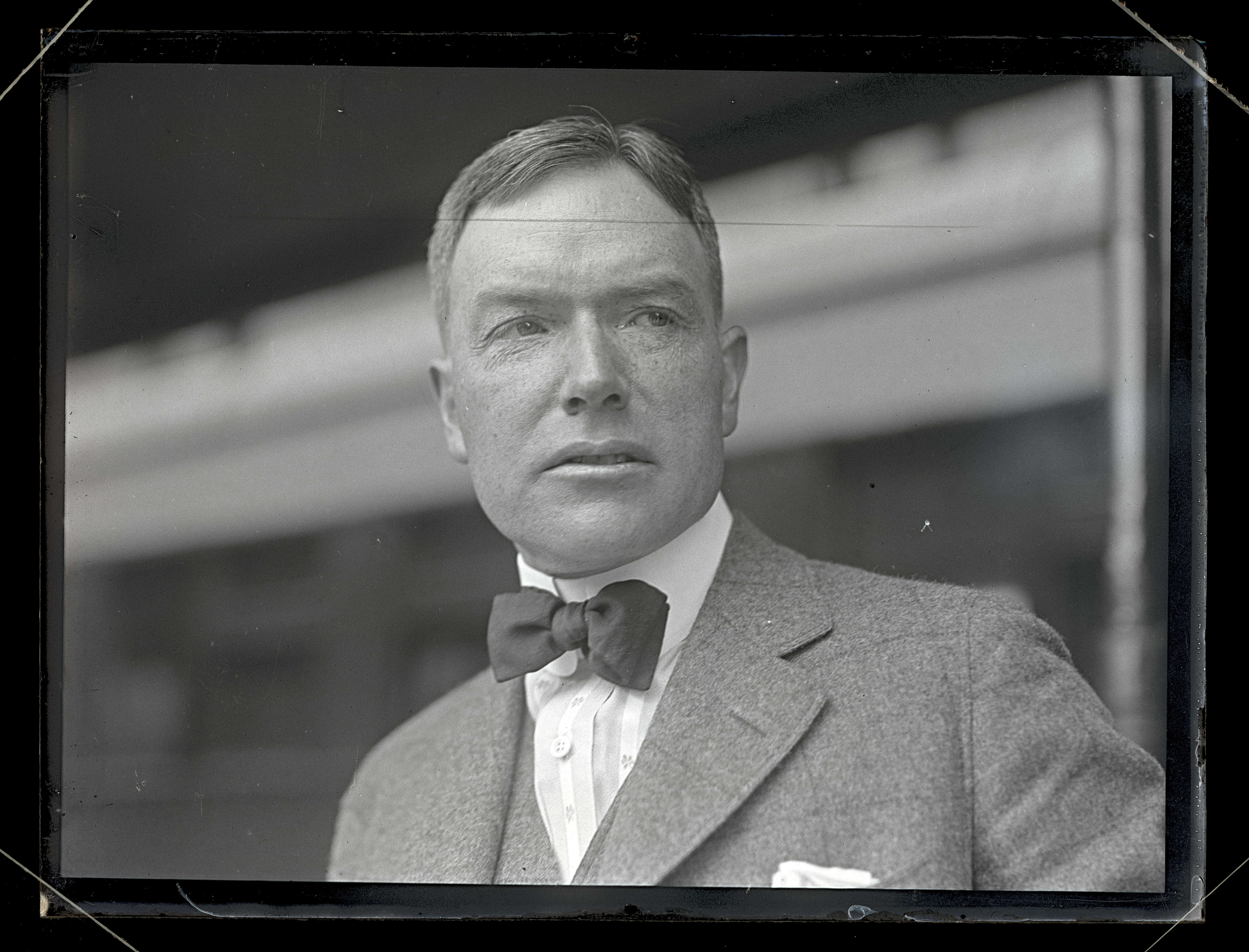

Guy Cordon, a self-effacing Republican tax attorney from Roseburg, long guided the economic fortunes of western Oregon as founder and head of the Association of O&C Counties. His diligence and effectiveness as a lobbyist helped reward the counties with a half-century-long bounty of federal dollars from harvesting timber on public lands that had once been part of the Oregon and California Railroad land grant. From his appointment to the U.S. Senate in 1944 until his defeat in a 1954 cliffhanger election, Cordon was what many consider to be the last dependably rock-solid conservative to represent the people of Oregon.

Born in Cuero, Texas, in 1890, Cordon was six months old when his family moved to Roseburg. After graduating from high school and studying accounting, at age nineteen he was named deputy tax assessor for Douglas County. Following stateside service in the U.S. Army during World War I, he studied law in the offices of county district attorney Carl Wimberly, who would become Cordon’s long-time mentor, patron, and friend. Over the years, his supporters and colleagues would include Roseburg newspaperman Charles Stanton and Congressman Harris Ellsworth.

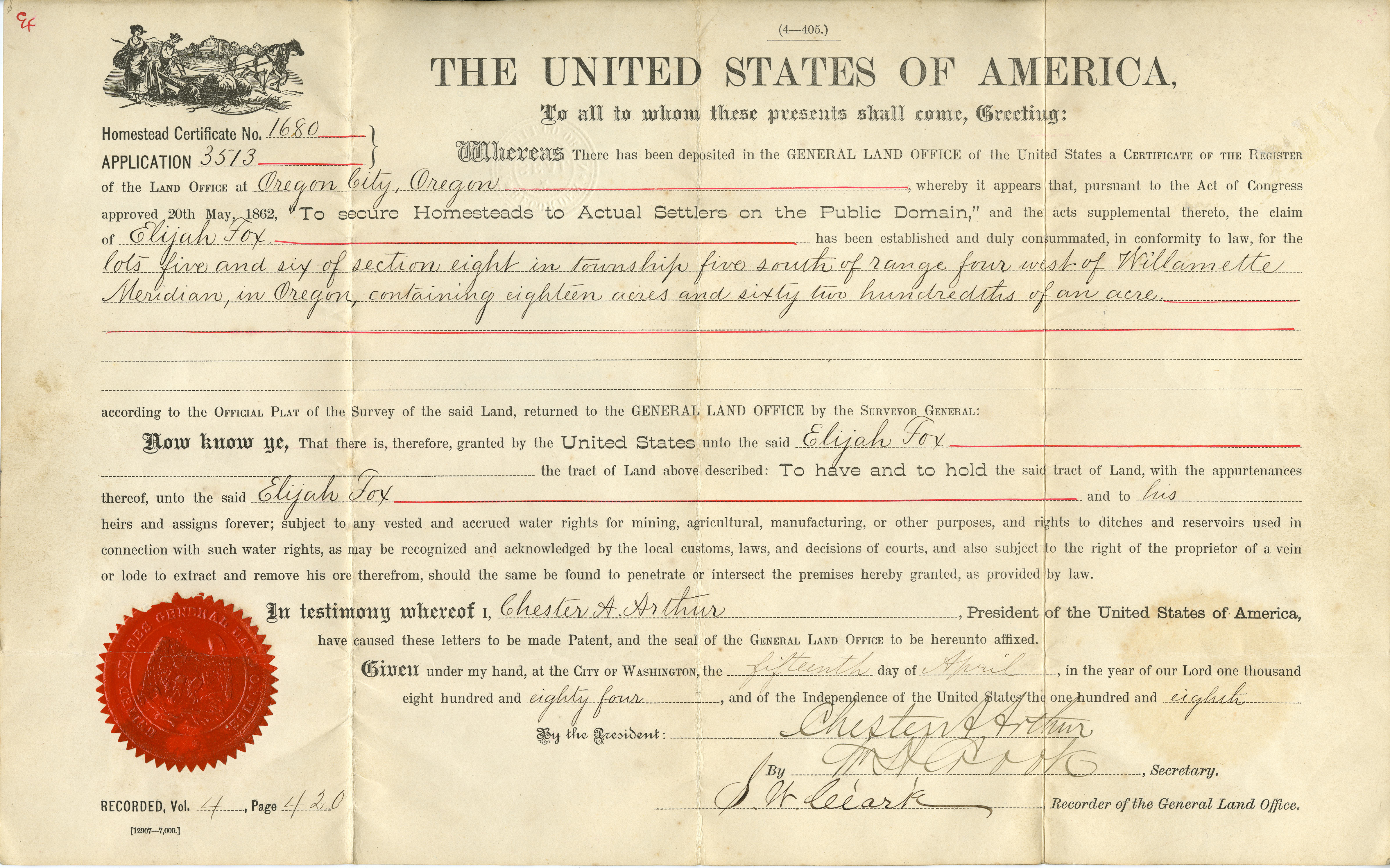

After passing the bar and succeeding Wimberly as district attorney in 1922, Cordon focused much of his energy on ensuring the continued timber harvest of the "revested" O&C Railroad Grant lands—that is, the lands that were returned to federal ownership by a 1915 Supreme Court decision and then implemented by the Chamberlain-Ferris Act of 1916. The lands were then managed by the U.S. General Land Office as a way to increase cash-strapped county coffers during the late 1920s and the early years of the Depression. The checker-boarded O&C lands—alternate one-square-mile sections—were originally meant to be sold off by the railroad company to bona fide settlers.

The Southern Pacific Railroad's subsequent failure to comply with the 1869 land-grant law led to years of litigation and an eventual U.S. Supreme Court victory by the government. Even after revestment, however, the intention remained to sell the lands to agricultural settlers, but only after the timber had been sold and harvested, with the federal receipts shared with the affected counties “in lieu of taxes.” Because Douglas County contained the largest acreage of western Oregon's revested O&C lands, as well as the heaviest volume of O&C timber, Cordon took the lead in protecting the interest of O&C counties. In 1935, he helped establish and was named director of the Association of O&C Counties (AOCC). He spent most of the next nine years in Washington, D.C., as its chief lobbyist.

With the Depression, the emerging concept of sustained-yield timber harvest replaced the long-held idea of selling off logged-over O&C lands to would-be farmers. By the mid-1930s, the issue was which formula Congress would use in the new legislation—that is, what percentage of total timber-sale receipts would be returned to the federal treasury and what percentage would stay in the counties in which the timber was situated. Cordon was doggedly instrumental in guiding the Oregon and California Lands Sustained-Yield Act to passage in 1937, legislation that ultimately gave O&C counties substantial revenue.

In 1944, having worked the halls of Congress in relative obscurity for a decade, Cordon was thrust into the limelight when conservative Republican Governor Earl Snell appointed him to fill the seat vacated in 1944 by the death of progressive Republican and Senate minority leader Charles L. McNary. Although many assumed that Cordon would serve as a short-term caretaker until Snell ran for the seat in the fall of 1944, Snell declined to run, and Cordon—a reluctant candidate and lackluster campaigner—emerged victorious in the primary and general elections.

One of a growing number of anti-New Deal/Fair Deal Republicans in the Senate, Cordon was a reliably conservative vote on most domestic and international issues, voting for the anti-labor Taft-Hartley Act and the isolationist Bricker Amendment. Like most of Oregon’s Republican leaders in the 1940s-1950s, he favored “termination policy” for the tribal status of the state’s Klamath, Siletz, and Grand Ronde tribes and their reservations, but, unlike fellow Secretary of Interior (and fellow Oregon Republican) Douglas McKay, Cordon urged closer direct consultation with the Klamath tribal members in particular on the specifics of termination legislation. Senator Cordon was also a relentless budget cutter of federal programs and government workers’ pay. By 1949, although on personally friendly terms with fellow World War I artillery veteran Harry Truman, Cordon painted Democrats as "soft on Communism" and as fellow travelers. Although not a demagogue himself, he quietly welcomed Senator Joseph McCarthy's speeches and hearings as the start of a long-overdue crusade against what was known as the Red Menace.

Senator Cordon saw no irony in Oregon receiving large amounts of federal taxpayer-generated funds. Among his favorite projects were McNary Dam on the Columbia River and the construction of thousands of miles of mountain roads in western Oregon to facilitate harvest on O&C and national forest lands. When it came to the Northwest's hydroelectric power, however, Cordon's preference for the interests of private over public utilities proved an Achilles heel. In 1954, Democratic challenger Richard Neuberger's aggressive campaign against what he called a Republican "giveaway" of the public's rights resonated at the same time that Democratic voter registration in Oregon was increasing. In a campaign that was further compounded by the effects of a bitter 1954 strike by millworkers in northwestern Oregon, Cordon suffered a narrow defeat.

Cordon remained in Washington, D.C., with his wife Ana. He formed a law firm, which lobbied for AOCC interests until Lane County Democrats (including future Oregon Governor Robert Straub) objected to Cordon's employment by AOCC as a political sinecure. The Senate continues to abide by the "Cordon Rule," which requires committees to discuss in detail how any proposed legislation would affect existing law.

Cordon died in Washington, D.C., from a malignant brain tumor on June 8, 1969. He was buried in Roseburg.

-

![]()

Guy Cordon, 1944.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 001522

-

![]()

Cordon (right) at reelection campaign picnic, Jantzen Beach, 1954.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi74281

-

![]()

Ana Cordon, 1948.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 001523

-

![]()

Joseph Carson (seated center), Wayne Morse, Condon, and Sen. Warren Magnuson (WA) discuss Carson's appt to Maritime Commission, 1947.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 001098

-

![]()

Guy Cordon questions Asst Sec. of Interior, C. Girard Davidson, in 1948 hearing about western timberlands.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi74289

-

![L-R: W. Harris Ellsworth, Cordon, Homer Angell, lawyer Frank Sever, and A. Walter Norblad.]()

Oregon congressional delegation celebrating election victory, 1952.

L-R: W. Harris Ellsworth, Cordon, Homer Angell, lawyer Frank Sever, and A. Walter Norblad. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 001534

-

![Eisenhower (seated left), Condon (seated right); l-r, Peter Mack, Sam Coon, and M. Harris Ellsworth.]()

NW congressmen invite Eisenhower to McNary Dam dedication, 1954.

Eisenhower (seated left), Condon (seated right); l-r, Peter Mack, Sam Coon, and M. Harris Ellsworth.

Related Entries

-

![Charles L. McNary (1874-1944)]()

Charles L. McNary (1874-1944)

Charles Linza McNary represented Oregon in the U.S. Senate from 1917 un…

-

![Earl Wilcox Snell (1895–1947)]()

Earl Wilcox Snell (1895–1947)

Earl Snell was a Republican governor of Oregon who served during World …

-

![Oregon and California Lands Act]()

Oregon and California Lands Act

The Oregon and California Lands Act, heralded as a forward-looking cons…

-

![U.S. General Land Office in Oregon, ca. 1850-1946]()

U.S. General Land Office in Oregon, ca. 1850-1946

With the acquisition of the Oregon Country in 1846, the United States w…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

LaLande, Jeff. “Oregon's Last Conservative Senator: Some Light upon the Little-Known Career of Guy Cordon.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 110:2 (2009), 228-261.

Richardson, Elmo. BLM's Billion-Dollar Checkerboard: Managing the O&C Lands. Santa Cruz, Calif.: Forest History Society, 1980.