Oregonians were light-headed from days of celebrating the end of World War I in November 1918. They filled Portland’s downtown streets—and Main Streets across the state—with rousing cheers that the carnage of the war had ended. Lurking in the war’s wake, however, was lingering anxiety about threats from within the nation’s borders. The Woodrow Wilson administration had so effectively inflamed Americans with a fear of dissent, radical politics, and dissidents in the country, that many citizens—along with city and state leaders—favored even more vigorous and punitive measures after the war ended.

Federal legislators had adopted the Espionage and Sedition Acts to rid the country of foreign agents and to silence dissidents during the war years. The Justice Department, in turn, enforced the wartime acts and harassed, deported, and jailed not only foreign radicals but anyone who dissented against the war, the government, and the “American way of life.” Rights to free speech and free assembly were shoved aside. When the federal government scaled back its anti-radical campaign at the end of the war, the states stepped up with their own initiatives.

More than two-thirds of the states, especially in the West, adopted Criminal Syndicalism Acts to counter the radicalism that had staked a foothold in their jurisdictions. Like the federal war acts, the state laws sought to silence dissenters, punish agitators, and destroy radical organizations. (The word syndicalism reflects the French “syndicat” or trade union and refers to a doctrine of direct action by the working class to seize control of the economy and abolish the capitalist state).

In January 1919, Oregon legislators introduced a bill for enactment of criminal syndicalism, modeled after statutes enacted in Washington and Idaho. The proposed legislation met little opposition and garnered bipartisan support. All but four members of the Oregon House approved Bill #1. (The four opponents feared the law would be used against trade unions and their members). A comparable state Senate Bill #2 passed 29-1 in that chamber. Governor James Withycombe (Republican) signed the Oregon Criminal Syndicalism Statute of 1919 on February 3, 1919.

The statute targeted any individual who by word of mouth or in writing advocates, suggests, recommends, teaches, or distributes any material that urges committing violent acts to effect industrial or political change. Anyone found to be in violation of the law was guilty of a felony punishable by one to ten years in the state penitentiary, a fine up to $1000, or both. The state also went after property owners, building agents, and superintendents who made their facilities available for assembly by radical persons whose activities or beliefs were prohibited by the statute. The penalties for this offense were up to a year in prison, a fine of $500, or both.

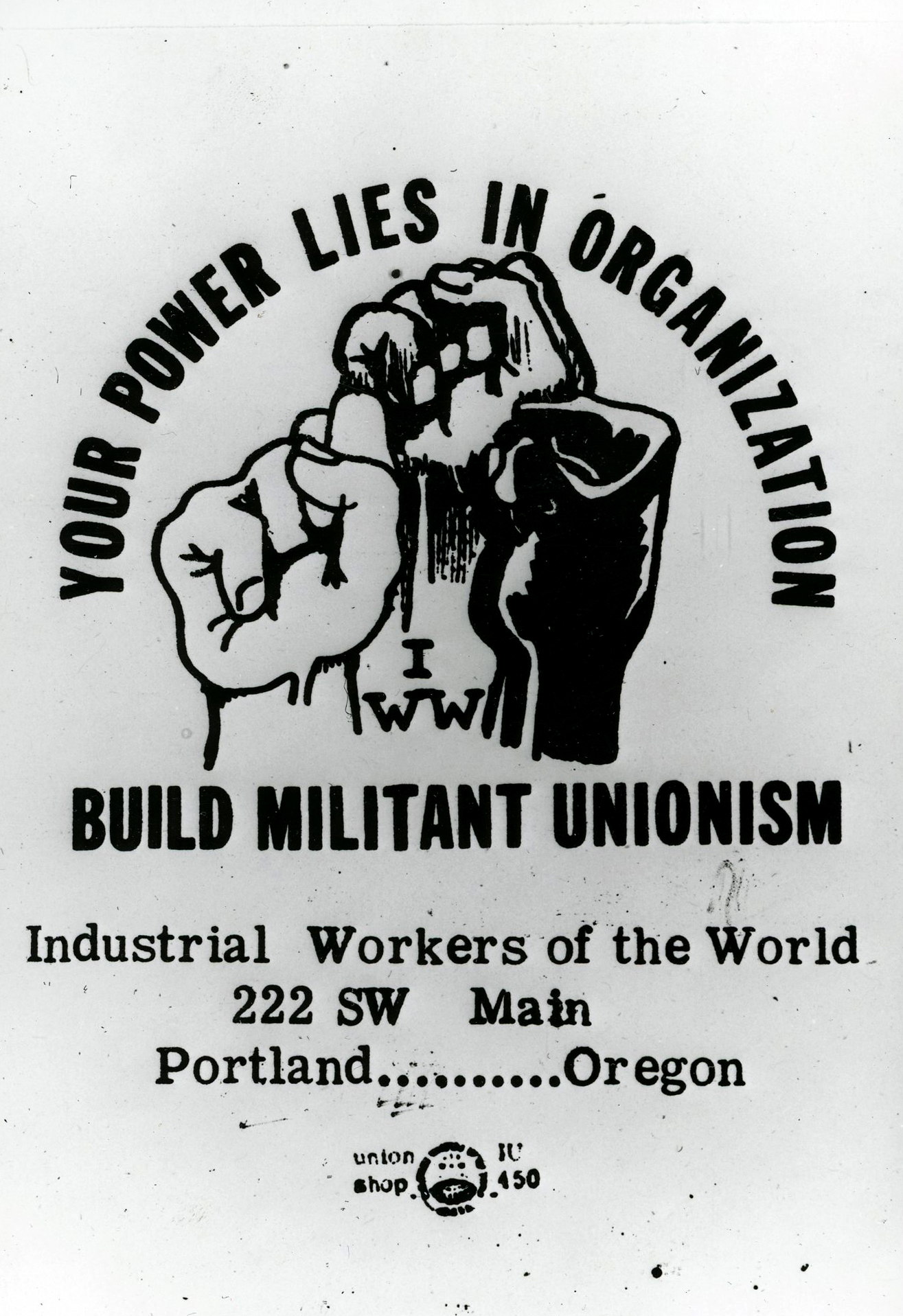

In Oregon, as well as in other western states, the primary target of the surveillance, enforcement, and punishment under the new law was the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a radical union that became the embodiment of leftist radicalism in the United States. Established in 1905 in Chicago, the IWW believed in “One Big Union” that all workers helped manage, operate, and own together for the common good. The IWW ideology espoused better working and living conditions in the lumber mills of western Oregon and the agricultural fields of eastern Oregon. That agenda was difficult to resist for laborers enduring wretched, unhealthy job environments. The inevitable clash of interests led to labor unrest, strikes, sabotage, violence, and sometimes death during the early 1900s.

The “Bolsheviks” of the Communist Party USA, the Socialist Party, and unaffiliated leftists were also subjected to the strictures of the new statute. State Senator Walter A. Dimick, a sponsor of the legislation, made its intent clear: “There shall be no IWW ism, no Bolshevism and no other 'ism' which advocates violence or crime…to preserve our true Americanism.”

On February 9, 1919, just six days after the anti-sedition statute took effect, Portland police arrested five men who had distributed radical brochures. That same day the police arrested a man for carrying a banner for the meeting of a radical union. Following the arrest, authorities raided the offices of the small organization and confiscated alleged seditious materials. On February 10, a judge of the municipal court released, for lack of evidence, eight men arrested under the suspicion of criminal syndicalism and violent intent or activity. Even with these and several other arrests, U.S. Military Intelligence reported several days later that “IWW Portland very quiet since passage of syndicalist law… headquarters at 2nd and Couch to close at request of the building owner, A.L. Parkhurst, due to syndicalist law that makes owners of buildings liable for acts committed within it in violation of the syndicalist law.

Arrests continued in Portland. On February 25, 1919, federal agents along with county and city police raided the IWW hall at 109 Second Avenue, arrested twenty-two men, and trashed the offices. Citizens were charged with vagrancy, and non-citizens were held for deportation. The vagrancy charges were part of a scheme on the part of Portland authorities to sweep a large number of suspects from the streets, charge them with vagrancy, and hold and indict them or keep them until the IWW bailed them out. The authorities expected suspects would be kept from organizing on the streets, and that IWW funds would be increasingly depleted after many bail payments.

During the next few years, approximately 200 men and a few women in the Pacific Northwest were charged with violations of the Criminal Syndicalism laws, specifically for the distribution of IWW literature or for carrying membership cards for the IWW, the Communist Party USA, or the Socialist Party. The IWW published on July 10, 1920, an account that revealed a number of convictions in Oregon, with 31 members facing indictments.

One well-known Portlander arrested under the new law was Dr. Marie Equi, not an IWW member but a sympathizer. Equi was arrested on the night of March 13, 1919, and charged with asking three adults and one girl to help distribute IWW literature on downtown streets. She was held overnight in jail, and her bail was set at $2,500, an exorbitant amount at the time. The next day she was released for lack of evidence. At the time, Equi was awaiting sentencing after being convicted of sedition under the federal Sedition Act.

While most of the arrests in Oregon under the Criminal Syndicalism Law occurred in Portland, arrests and prosecutions also took place in Tillamook, Condon, and Klamath Falls. In February 1923, North Bend officials arrested two IWW members for distributing literature announcing an upcoming IWW meeting.

Oregon’s statute was revised slightly in 1921 to broaden its reach beyond those joining radical organizations to include existing members, and then revised more extensively in 1930 (and amended in 1933) to more specifically find individuals guilty of a felony for becoming a member of any group that taught or advocated criminal syndicalism. Oregon’s criminal syndicalism law was a major determinant for the significant decline in influence of the IWW in the state, but as times changed and public attitudes shifted, the statute itself became untenable.

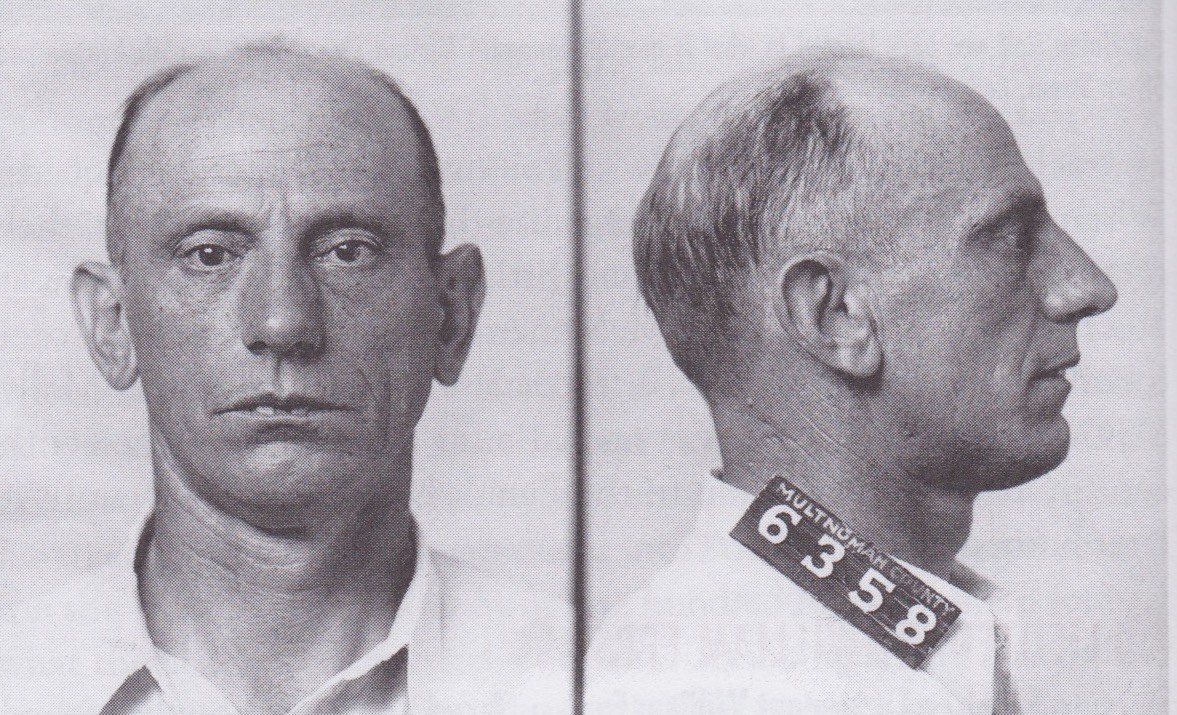

The most significant prosecution in Oregon involved Dirk De Jonge, a WWI veteran, longshoreman, and communist who lived in Portland. He addressed an audience and helped conduct a meeting convened by the Communist Party. He was arrested, charged with violation of the criminal syndicalism law, convicted, and sentenced to a stiff prison term. On appeal, the Oregon State Supreme Court upheld his conviction on November 26, 1934. De Jonge appealed to the nation’s highest court. A young Portland attorney named Gus Solomon filed the brief. On January 4, 1937, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the De Jonge conviction and declared unconstitutional much of the criminal syndicalism law. In a unanimous decision the court ruled the criminal syndicalism law violated the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The court also affirmed the right of peaceable assembly. Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes wrote, “We hold that the Oregon statute….is repugnant to the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.” The decision proved to be a death knell for Oregon’s anti-syndicalism law. De Jonge v. Oregon strengthened Americans' fundamental rights, including the right to meet and peaceably dissent in meetings, rallies, and demonstrations, no matter the content.

The criminal syndicalism law served its purpose in effectively ending the influence of the IWW in Oregon, but changing times, the evolving legal interpretation of fundamental rights, and the public’s refusal to support ongoing trampling of citizen rights brought the Oregon Criminal Syndicalism Statute to its end. Oregon legislators finally repealed the law on February 20, 1937.

-

![]()

Mugshot of Dirk De Jong, Oregon communist who helped repeal the Criminal Syndicalism law.

Courtesy U.S. District Court Historical Society

-

![(full article under document tab)]()

"Syndicalism is a Trap," Oregonian, November 15, 1919.

(full article under document tab) Courtesy Portland Oregonian, November 15, 1919

-

![]()

"Syndicalism Bill Opposed by Labor," Oregonian, January 23, 1919.

Courtesy Portland Morning Oregonian, January 23, 1919

-

![]()

"Dr. Equi is Rearrested," Oregonian, March 14, 1919.

Courtesy Portland Oregonian, March 14, 1919

Related Entries

-

![Gus J. Solomon (1906–1987)]()

Gus J. Solomon (1906–1987)

Gus J. Solomon, the second-longest-serving federal judge in Oregon hist…

-

![Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)]()

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or "Wobblies"), founded in 190…

-

Marie Equi (1872-1952)

Dr. Marie Equi was a fiercely independent Oregon physician who was enga…

-

![Socialist Party of Oregon]()

Socialist Party of Oregon

The Socialist Party of Oregon was founded in 1901, at the same time as …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

“Dissent and World War I in the United States and Oregon."

Mayer, Heather. Beyond the Rebel Girl: Women and the Industrial Workers of the World in the Pacific Northwest, 1905-1924. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2018.

Helquist, Michael. Marie Equi: Radical Politics and Outlaw Passions. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2015.

Stone, Geoffrey R. Perilous Times, Free Speech in Wartime.” New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2004.

White, Ahmed A. ‘The Crime of Economic Radicalism: Criminal Syndicalism Laws and the Industrial Workers of the World, 1917-1927.” Oregon Law Review 85.649: 649-770.