Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws that were in place during much of the region's early history. These laws, all later rescinded, largely succeeded in their aim of discouraging free Black people from settling in Oregon early on, ensuring that Oregon would develop as primarily white.

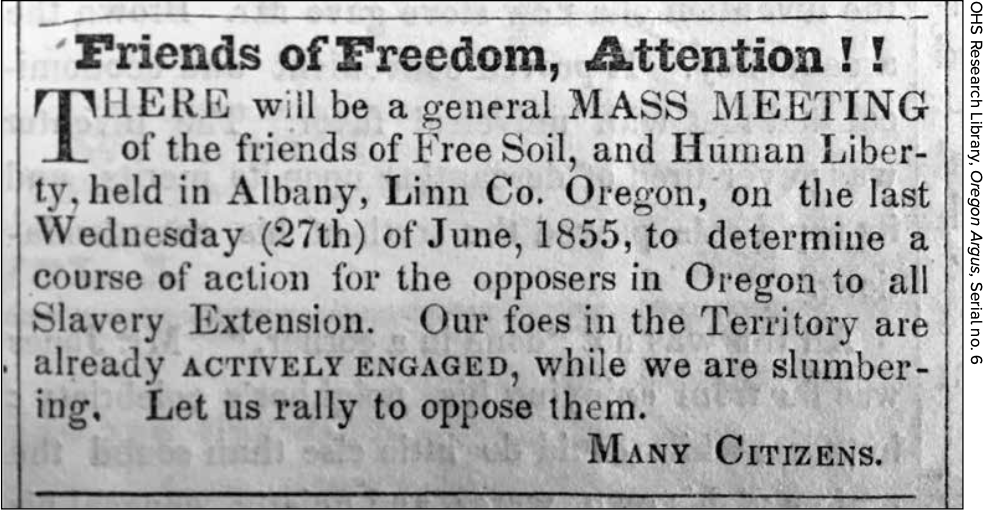

White emigrants who came to present-day Oregon during the 1840s and 1850s generally opposed slavery, but many also opposed living alongside African Americans. Many were nonslaveholding farmers from Missouri and other border states who had struggled to compete against those who owned slaves. To avoid a similar competitive situation in Oregon, they favored excluding Black people entirely, although a small number did settle in region. A few immigrants brought slaves to Oregon during this time, taking advantage of the lack of enforcement of Oregon's anti-slavery laws.

Oregon's small white population had voted on July 5, 1843, to prohibit slavery by incorporating into Oregon's 1843 Organic laws a provision of the 1787 Northwest Ordinance: "There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.'' The law was amended, however, on June 26, 1844, by the provisional government's new legislative council, headed by Missouri immigrant Peter Burnett. As amended, the law prohibited slavery, gave slaveholders a time limit to “remove” their slaves “out of the country,” and freed slaves if their owners refused to remove them.

The effect was to legalize slavery in Oregon for three years. Moreover, once freed, a former slave could not stay in Oregon—a male would have to leave after two years, a female after three. Any free Black person who refused to leave would be subject to lashing, a provision that was known as "Peter Burnett's lash law." Burnett, who later became the first U.S. governor of California, gave this explanation for his support for the law: "The object is to keep clear of that most troublesome class of population [Black people]. We are in a new world, under the most favorable circumstances and we wish to avoid most of those evils that have so much afflicted the United States and other countries.''

Because the lashing penalty was judged to be unduly harsh, the council substituted a lesser penalty later that year, and voters rescinded the law in 1845 before anyone could be punished. The law did discourage at least one Black settler—George Bush, who had been born in Pennsylvania and was a successful farmer in Missouri. After arriving in Oregon with his wife and six sons, he decided to settle north of the Columbia River near Puget Sound, out of the reach of the 1844 Oregon law.

The second exclusion law was enacted by the Territorial Legislature on September 21, 1849. This law specified that “it shall not be lawful for any negro or mulatto to enter into, or reside” in Oregon, with exceptions made for those who were already in the territory. The law targeted African American seamen who might be tempted to jump ship. The preamble to the law addressed a concern that African Americans might “intermix with Indians, instilling into their minds feelings of hostility toward the white race.'' The law was rescinded in 1854.

At least one person was expelled under the law. Jacob Vanderpool, reportedly a sailor from the West Indies, arrived in Oregon in 1850 and was arrested and expelled from the territory. Exclusion orders were issued against at least three other Black people during this period, but they received enough support from whites that they were allowed to stay.

Delegates to Oregon's constitutional convention submitted an exclusion clause to voters on November 7, 1857, along with a proposal to legalize slavery. Voters disapproved of slavery by a wide margin, ensuring that Oregon would be a free state, and approved the exclusion clause by a wide margin. Incorporated into the Bill of Rights, the clause prohibited Black people from being in the state, owning property, and making contracts. Oregon thus became the only free state admitted to the Union with an exclusion clause in its constitution.

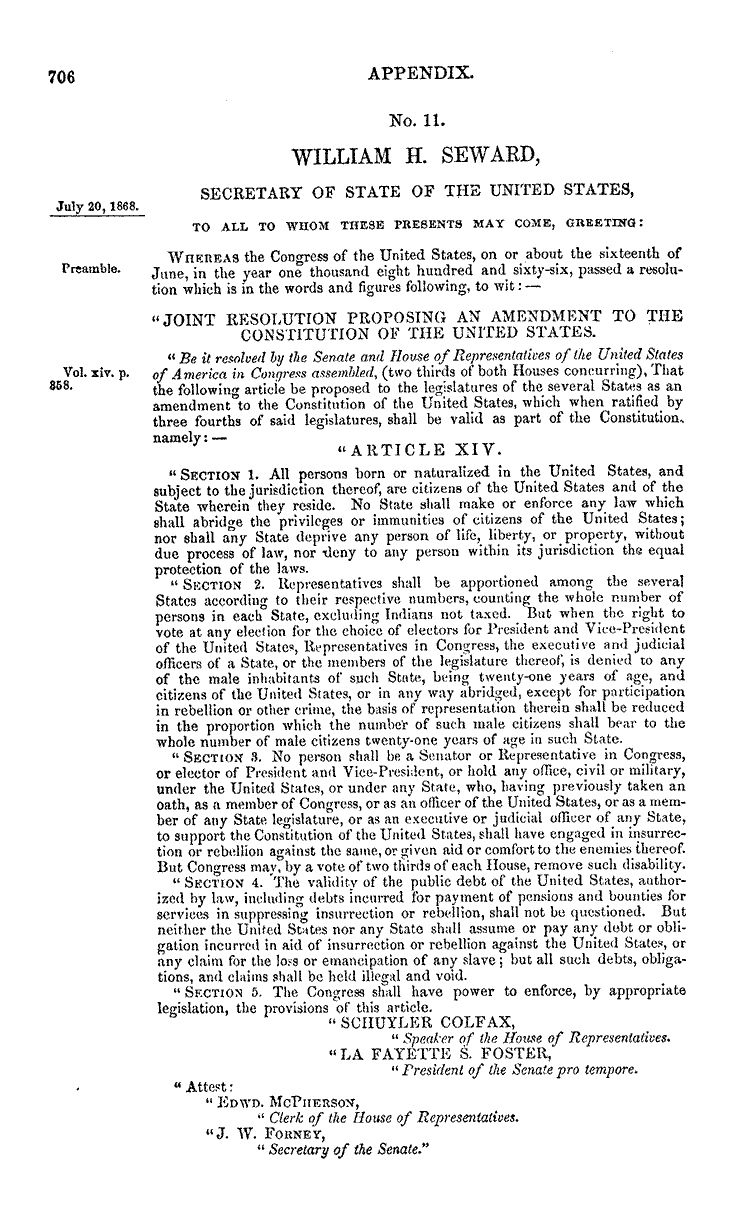

The clause was never enforced, although several attempts were made in the legislature to pass an enforcement law. The 1865 legislature rejected a proposal for a county-by-county census of Black people that would have authorized the county sheriffs to deport them. A Senate committee killed the last attempt at legislative enforcement in 1866. The clause was rendered moot by the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, although it was not repealed by voters until 1926. Other racist language in the state constitution was removed in 2002.

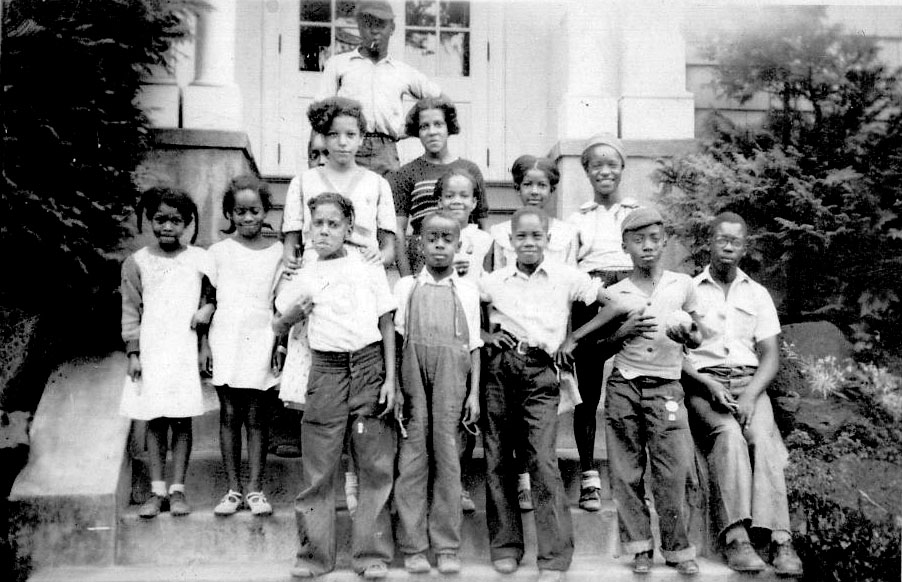

Although the exclusion laws were not generally enforced, they had their intended effect of discouraging Black people from settling in Oregon. The 1860 census for Oregon, for example, reported 128 African Americans in a total population of 52,465. In 2013, only 2 percent of the Oregon population were Black people.

-

![Middle columns tabulate votes for and against slavery and Black exclusion.]()

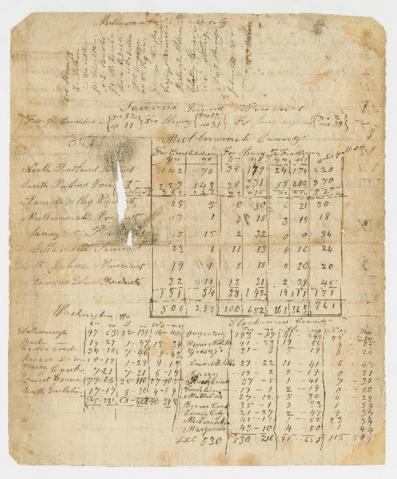

Preliminary abstract of votes, November 1857.

Middle columns tabulate votes for and against slavery and Black exclusion. Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Mss1231_Box01Folder01_001 -

![Section of Oregon State Constitution outlining slavery and exclusion laws, from the 1857 document distributed to Oregonians.]()

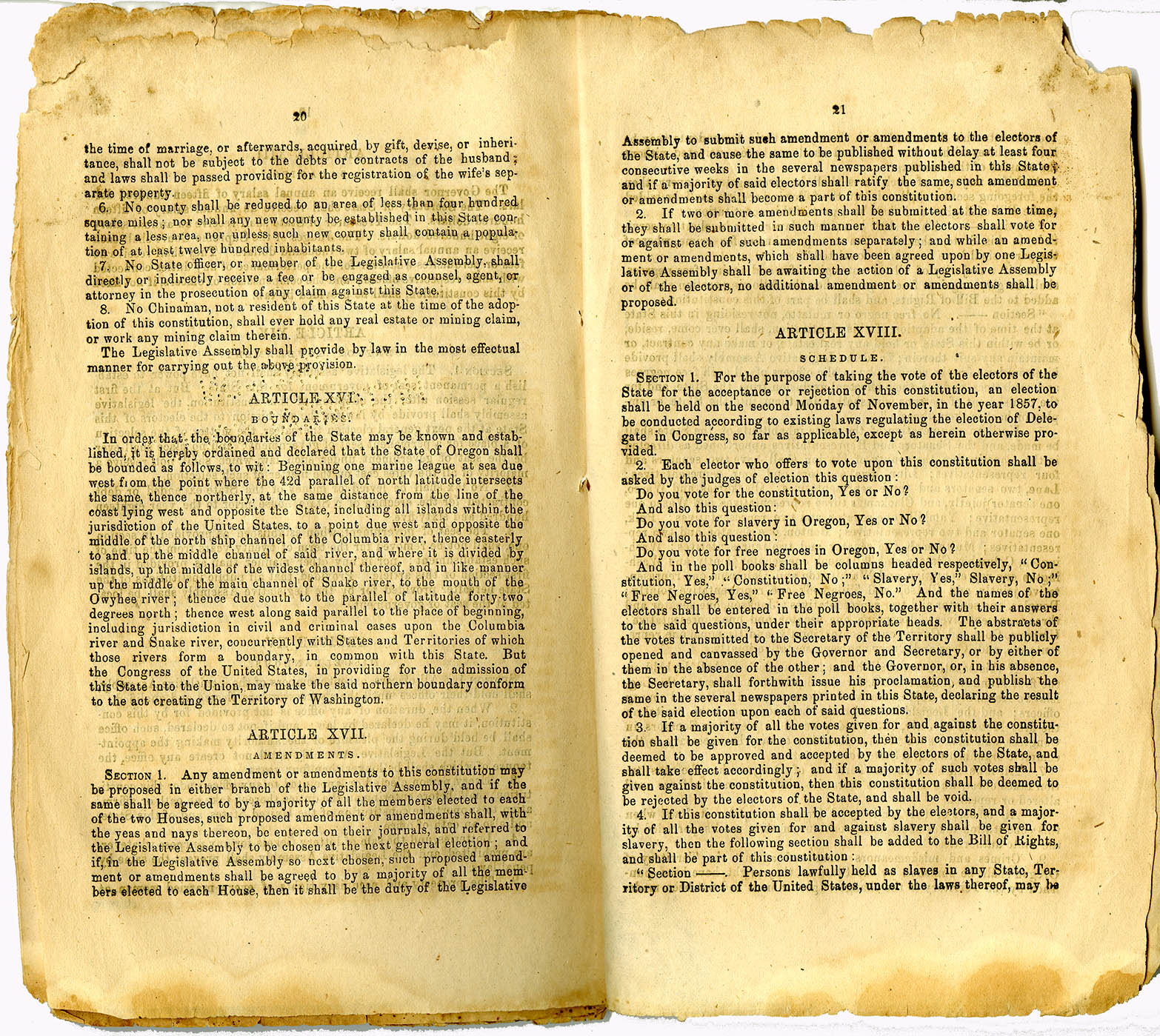

Article XVIII, from the State Constitution.

Section of Oregon State Constitution outlining slavery and exclusion laws, from the 1857 document distributed to Oregonians. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Belknap 295

-

![Section of Oregon State Constitution outlining slavery and exclusion laws, from the 1857 document distributed to Oregonians.]()

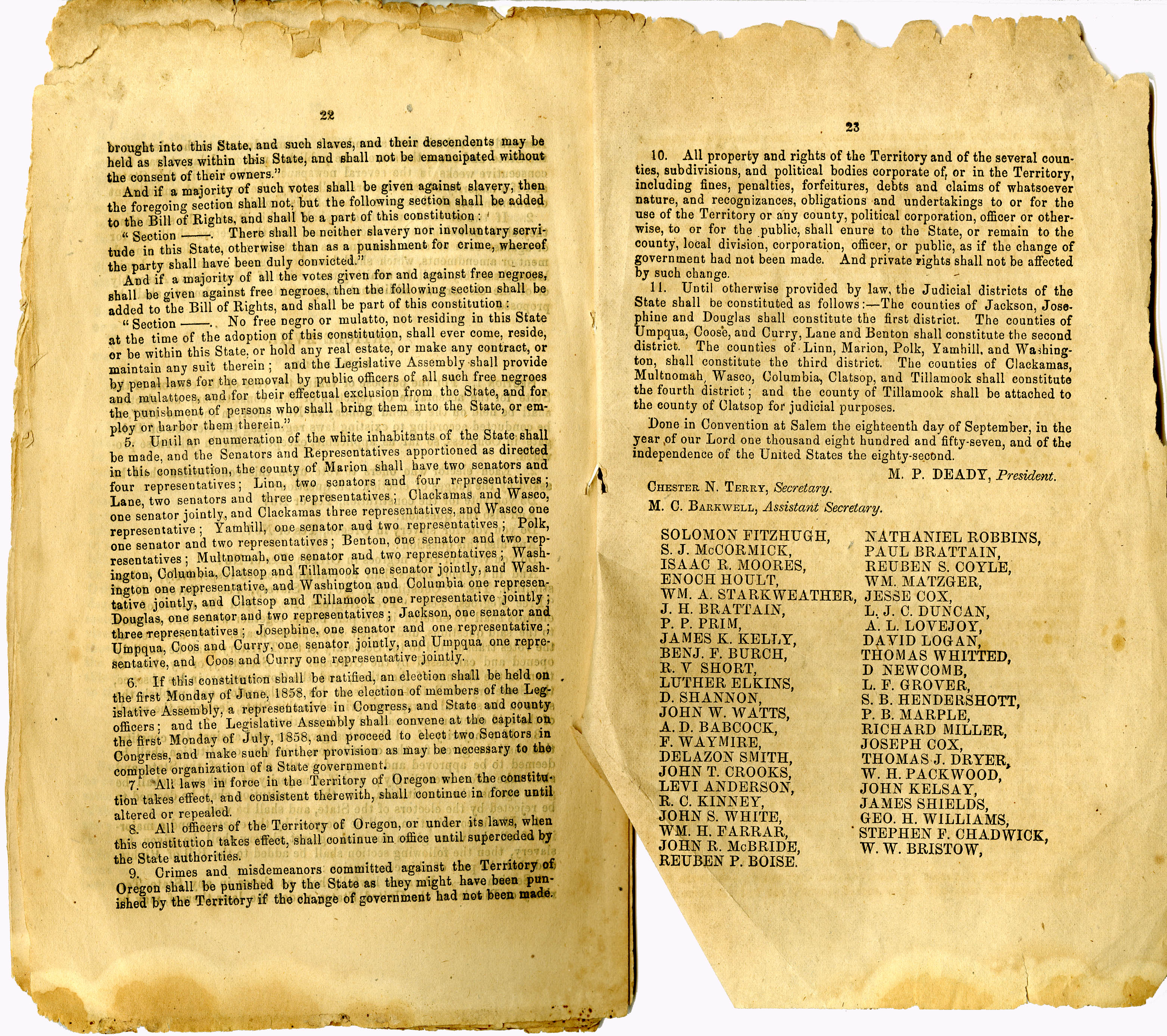

Article XVIII, from the State Constitution (second part).

Section of Oregon State Constitution outlining slavery and exclusion laws, from the 1857 document distributed to Oregonians. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, Belknap 295

-

![]()

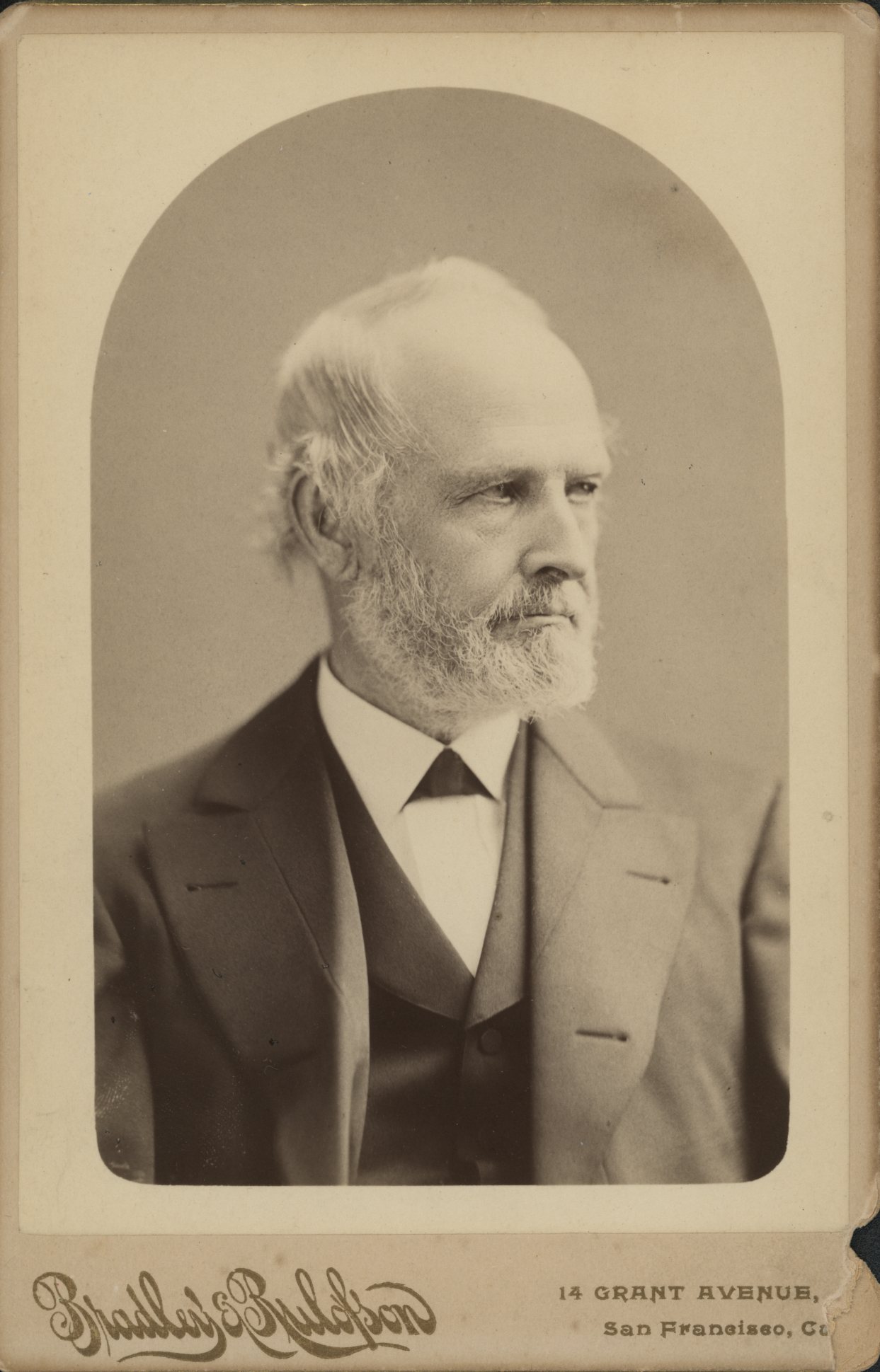

Peter Burnett.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi46162

Related Entries

-

![14th Amendment]()

14th Amendment

The Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution declared that the fed…

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![George Bush (c. 1790-1863)]()

George Bush (c. 1790-1863)

George Bush, sometimes named as George Washington Bush in the historica…

-

![Henry Hamilton Hicklin (1825–1873)]()

Henry Hamilton Hicklin (1825–1873)

White supremacy dominated opposition to slavery in mid-nineteenth-centu…

-

![Holmes v. Ford]()

Holmes v. Ford

On April 16, 1852, a former slave named Robin Holmes filed suit against…

-

![Peter Burnett (1807-1895)]()

Peter Burnett (1807-1895)

Peter Hardeman Burnett was a leader on the Oregon Trail, a town-builder…

-

![Provisional Government]()

Provisional Government

The Provisional Government, created in May-July 1843, was the first gov…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Nokes, R Gregory. Breaking Chains: Slavery on Trial in the Oregon Territory. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2013.

Carey, Charles H. General History of Oregon: Through Early Statehood. Portland, Ore.: Binfords & Mort, 1971.

Carey, Charles H. The Oregon Constitution and Proceedings and Debates of the Constitutional Convention of 1857. Salem, Ore.: State Printing Department, 1926.

Burnett, Peter H. Recollections and Opinions of an Old Pioneer. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1880.