Fernando is a trickster, the character in traditional Basque folk tales who disobeys normal behavioral rules, outsmarts a figure of authority (such as the priest), and overcomes oppression or discrimination. Fernando is lazy, greedy, and always hungry; he depends on wit and double entendre to obtain his ends. Basque immigrants in Oregon and Idaho may have had an appreciation for tales of Fernando cleverly outsmarting a priest.

It is possible that Fernando is based on a historical person. The tales may have originated with Fernando Bengoetchea—elsewhere known as Fernando Bengoetxea Altuna and Pernando Amezketarra—who was born in the village of Amezquete in southern Guipuzcoa, Spain, in 1764. Fernando was a shepherd and a bertzolari, a person who improvises his own verses as he sings them, often on political themes.

Tales about Fernando were collected in eastern Oregon and western Idaho in 1970, and they resemble stories collected earlier in the same area. One begins with the priest inviting Fernando to dinner but neglecting to invite his son. The priest asks Fernando to give the blessing, and Fernando responds: "In the name of the Father and the Holy Ghost." The priest asks: "Fernando, what happened to the Son?" Fernando quickly responds: "Oh, he's waiting outside. I'll ask him in." Then he goes to the door to let his son join the dinner.

In another tale, the priest is just sitting down to dinner when Fernando comes. The priest cannot turn him away, so they sit down to eat. The priest has two pieces of meat on the platter, one large and one small. He puts the large one close to himself, because he does not think Fernando would be so crude as to reach across the table for the larger piece. They begin talking about a neighbor, and the priest asks: "What would you do with someone like that?" Fernando answers: "Well, I'd twist his neck just like this." And he turns the platter so the larger piece of meat is on his side.

In another of the many tales, Fernando has a sister, but she dies. To get her to go to heaven, he has Masses said every two or three weeks. The priest charges him two or three dollars for each one. Pretty soon, Fernando runs out of funds, so Fernando goes to see the priest. The priest says: "Well, you better have another Mass. I think she's right on the brink." Fernando is her only living relative, since she was not married. Fernando says: "Well, you know she was an old maid." The priest responds: "No, she wasn't. She was married to God." Fernando counters: "Yes, well, you better have $100 worth of Masses." The priest then asks: "Who's going to pay for it?" Fernando replies: "Just charge it to my brother-in-law."

In eastern Oregon, Fernando tales were associated with life in Spain. They might have been told by immigrants while reminiscing about the past or talking about their memories of Spain.

-

![]()

Basque residents of Jordan Valley, c. 1914.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 21730

-

![]()

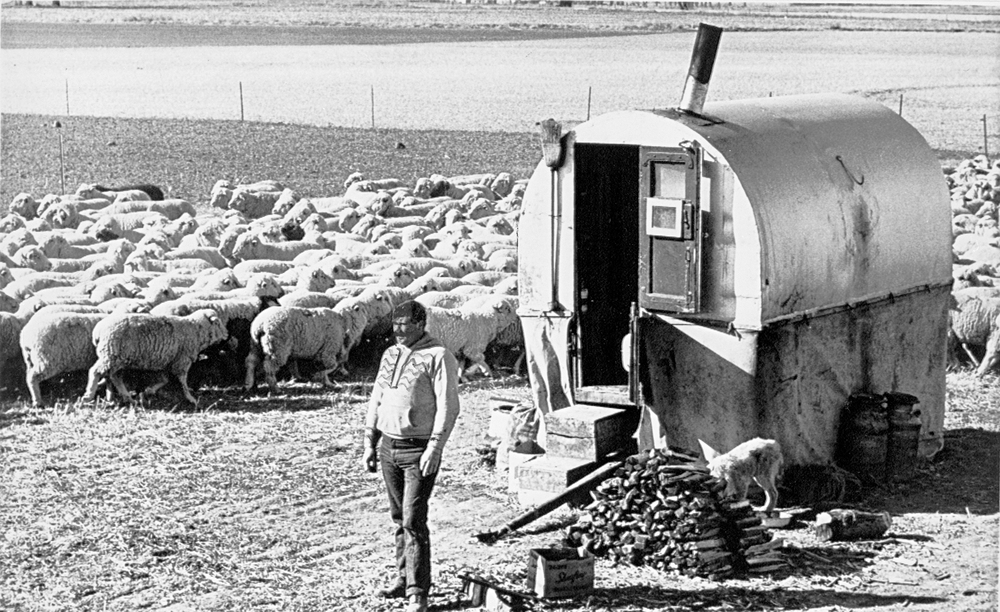

A Basque Sheepherder in the Jordan Valley.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, bb003838

Related Entries

-

![Basque boardinghouses in Oregon]()

Basque boardinghouses in Oregon

Oregon’s earliest Basque settlers arrived in the late 1880s from northe…

-

![Basques]()

Basques

The first Basques to Oregon arrived in the late 1880s. These Euskalduna…

-

![Pelota Fronton]()

Pelota Fronton

The pelota fronton in Jordan Valley is a handball court built by Basque…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Baker, Sarah Catherine. Basque Folklore of Eastern Oregon, MA Thesis in Folklore Program, Unviersity of California, Berkeley, 1972.

Gallop, Rodney. A Book of the Basques. Reprinted from original 1930 edition, Macmillan, London. Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1970.

Jones, Suzi, and Jarold Ramsey, eds. The Stories We Tell: An Anthology of Oregon Folk Literature. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1994.

Munro, Sarah Baker. "Basque Folklore in Southeastern Oregon." In Basques of the Pacific Northwest, ed. by Richard W. Etulain. Pocatello: Idaho State University Press, 1991.