During his service in the U.S. House of Representatives, John Floyd of Virginia was the first member of Congress to aggressively champion the occupation and colonization of Oregon. He represented northwestern Virginia in Congress from 1817 to 1829 and was the first to introduce legislation that referred to Oregon as a territory. He was never in Oregon Country.

Floyd’s enthusiasm for western expansion was reportedly influenced by his early upbringing on the Kentucky frontier. He was born in Floyds Station, Virginia (present-day St. Matthews, Kentucky), on April 24, 1783, two weeks after his father, for whom he was named, died in an Indian attack near his frontier home. Educated at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, he also attended the University of Pennsylvania Medical School. He married Letitia Preston, who was part of a wealthy family in Virginia, and practiced medicine in Christiansburg, south of Blacksburg. A surgeon in the War of 1812, he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1814. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, representing northwestern Virginia, in 1817.

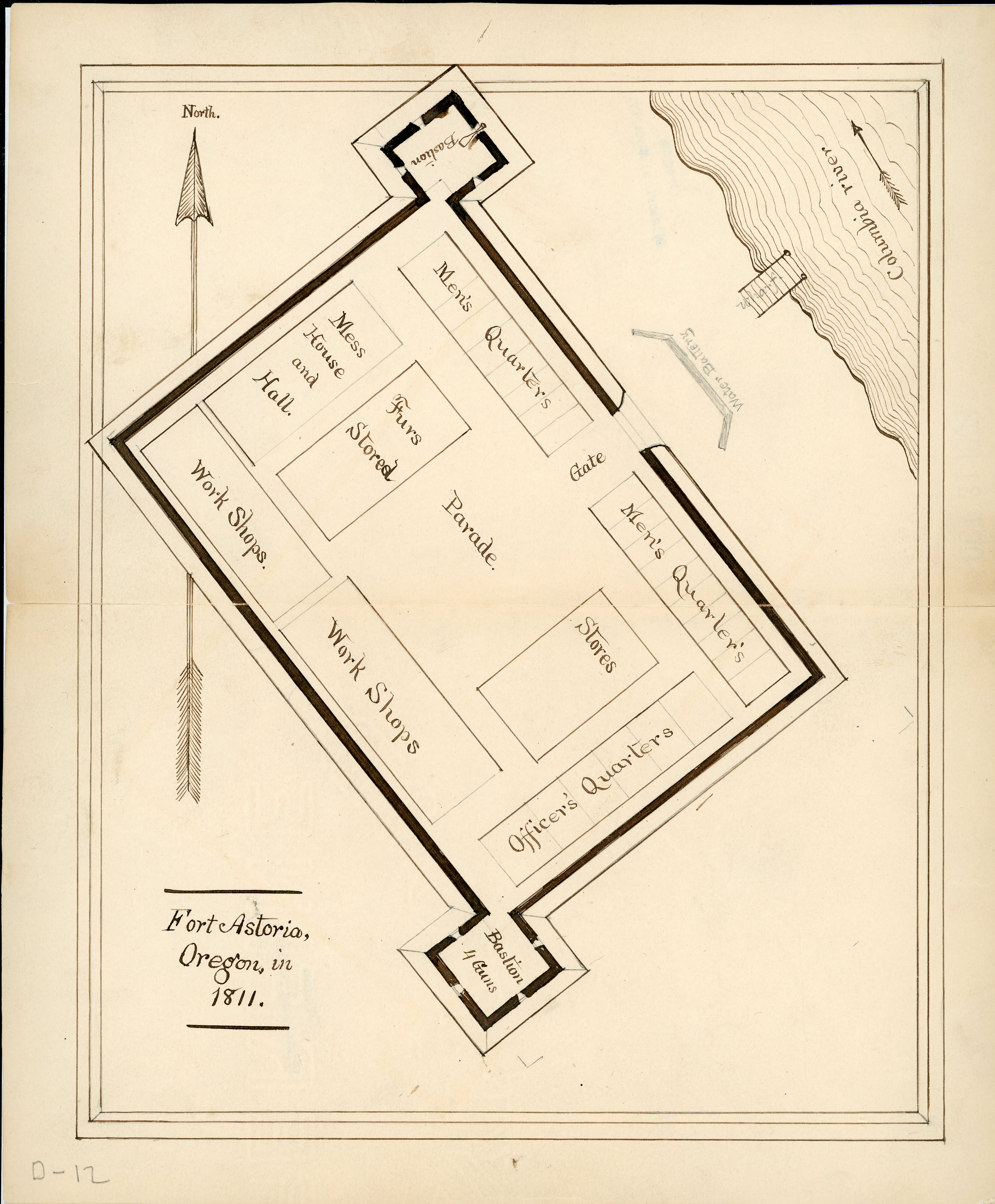

Floyd had an interest in Oregon long before his election to Congress. Charles Floyd, the only fatality suffered by the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery, had been his first cousin, and as a young man John Floyd had become acquainted with explorer William Clark. As a member of Congress, Floyd lodged at Brown’s Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue, a few blocks from the Capital. His interest in Oregon was reinvigorated in 1820 by conversations with fellow lodgers Thomas Hart Benton, the new U.S. senator from Missouri, and Russel Farnham and Ramsay Crooks, who had been part of the Astor Expedition to Oregon (1810–1813). The “conversation, rich in information upon a new and interesting country,” Benton wrote in his memoirs, “was eagerly devoured by the ardent spirit” of John Floyd.

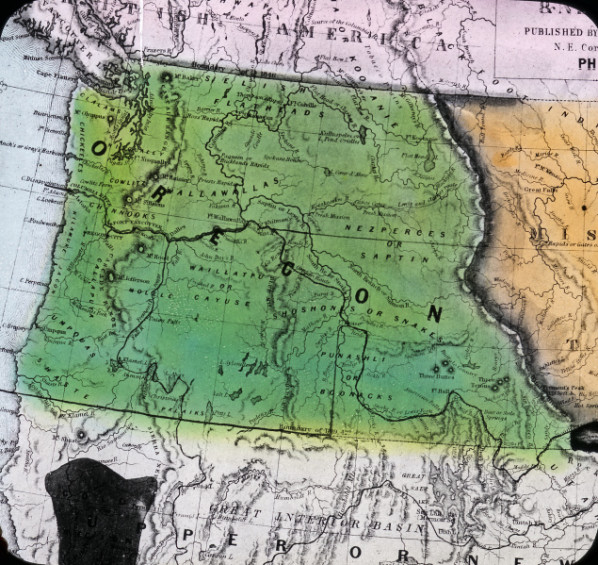

On December 20, 1820, Floyd introduced a resolution in the House calling for a committee to “inquire into the situation of the settlements upon the Pacific Ocean and the expediency of occupying the Columbia River.” The resolution passed, and Floyd chaired the committee that produced a lengthy report the following January, Occupation of the Columbia River, along with a bill to authorize the U.S. military occupation of the mouth of the Columbia. But Floyd’s efforts were in conflict with the nation’s 1818 treaty with Great Britain, which had established a ten-year joint occupation of the Oregon Country and included a provision that prohibited military installations by either nation. The House failed to act on the bill, and the report was not viewed favorably. It was “a tissue of errors in facts and abortive reasoning,” Secretary of State John Quincy Adams advised President James Monroe; “there was nothing that could purify it but the fire.”

Floyd was not deterred. In early 1822, he introduced the first bill that referred to Oregon as a “territory of the United States” and provided for land grants to settlers. Again, the bill languished. In December, President Monroe suggested a reconsideration of U.S. rights to the Pacific Coast in his message to Congress, and Floyd reintroduced his bill in January. This time the bill was put to a vote, which failed 61 to 100.

Floyd’s only success as a champion for Oregon came in 1825. After President Monroe again spoke favorably to Congress about a military presence on the Columbia, Floyd’s bill passed the House, 115 to 57. Despite Senator Benton’s advocacy, the bill was never voted on in the Senate. Floyd continued to introduce bills calling for the occupation and colonization of Oregon until he gave up his seat in the U.S. House in 1829. In 1830, he was elected as the twenty-fifth governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia. He served until 1834 and died in 1837.

John Floyd is little remembered in Oregon today, though he does appear among the 158 names that were chosen to appear around the top of the walls in the House and Senate Chambers of the State Capitol. Historian John Schroeder summed up Floyd’s contribution this way: “During the 1820s very few Americans were interested in the remote area known as Oregon.…two decades before this interest arose, John Floyd stood almost alone at the head of a tiny group of Americans who prophesied the future value of the Oregon region to the United States.”

-

![The painting, created posthumously, is part of the Commonwealth of Virginia's art collection.]()

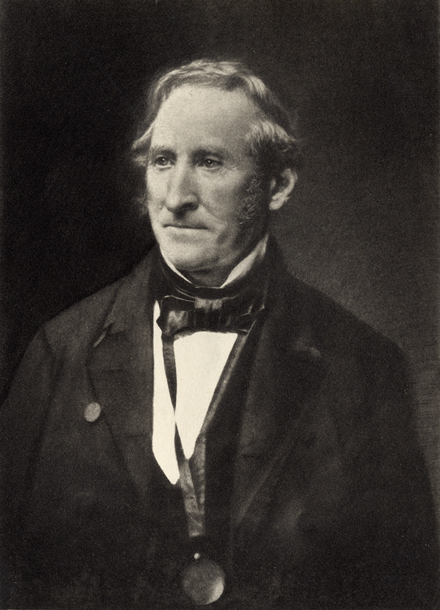

John Floyd, governor of Virginia from 1830 to 1834. Oil portrait by William G. Brown..

The painting, created posthumously, is part of the Commonwealth of Virginia's art collection. Courtesy Library of Virginia

Related Entries

-

![Astor Expedition (1810-1813)]()

Astor Expedition (1810-1813)

The Astor Expedition was a grand, two-pronged mission, involving scores…

-

![Hall Jackson Kelley (1790–1874)]()

Hall Jackson Kelley (1790–1874)

Hall Jackson Kelley of Massachusetts was a tireless promoter of the Ame…

-

![Lewis and Clark Expedition]()

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Expedition No exploration of the Oregon Country has greater histor…

-

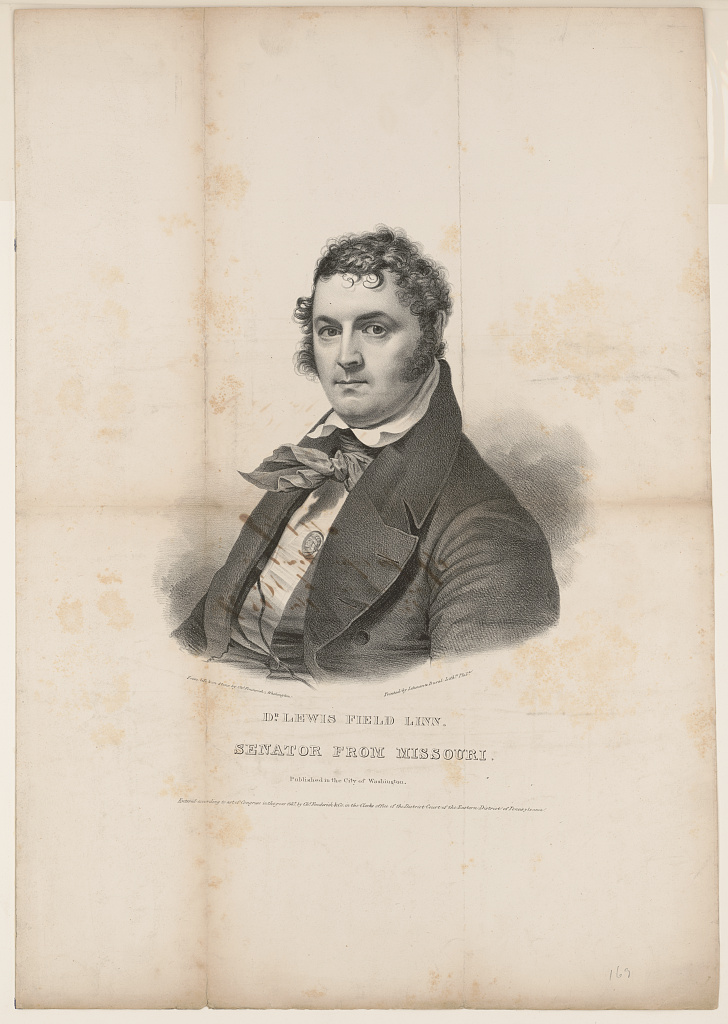

![Lewis F. Linn and Oregon]()

Lewis F. Linn and Oregon

Senator Lewis F. Linn of Missouri was a tireless advocate for the Unite…

-

![Oregon Question]()

Oregon Question

“The Oregon boundary question,” historian Frederick Merk concluded, “wa…

-

![Petitions to Congress, 1838-1845]()

Petitions to Congress, 1838-1845

Even before the first large wagon trains traveled the Oregon Trail to t…

-

![Thomas Hart Benton and Oregon]()

Thomas Hart Benton and Oregon

As a newspaper editor and then as a United States senator for Missouri …

Related Historical Records

Further Reading

Ambler, Charles H. The Life and Diary of John Floyd, Governor of Virginia, an Apostle of Secession and the Father of the Oregon Country. Richmont, Virg.: Richmond Press, 1918.

Floyd, John. “Occupation of the Columbia River — Floyd’s Report of January 25, 1821.” The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 8.1 (March 1907): 51–75.

Cogswell, Philip. Capitol Names: Individuals Woven Into Oregon's History. Portland: Oregon Historical Society, 1977.

Schroeder, John H. “Rep. John Floyd, 1817-1829: Harbinger of Oregon Territory.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 70.4 (December 1969): 340.