Forest Park is a unique and impressive recreational and scenic area established in Portland as a city park in 1948. The park covers 5,170 forested acres within the city limits, is roughly one mile wide and eight miles long, and provides a majestic green backdrop for the city’s west side.

Sitting atop the Tualatin Mountain Range, Forest Park is comprised primarily of Douglas-fir, western red cedar, western hemlock, and various deciduous varieties of trees and other native plants. More than 110 bird species and 62 mammal species can be found in the park. Portlanders revere the park for the eighty miles of recreational trails, including the thirty-mile Wildwood Trail, which is designated a National Recreation Trail, as well as the well-trod Upper and Lower Macleay Trails.

The first person to recommend that the forested hills be made into a park was landscape architect John L. Olmsted, who developed a citywide plan for Portland in 1903 in conjunction with the upcoming 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition. Olmsted, stepson of the famed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, strongly recommended that the “romantic wooded hillsides” be preserved as parkland, saying, “It is true that some people look upon such woods merely as a troublesome encumbrance standing in the way of more profitable use, but future generations will not feel so and will bless the men who were wise enough to get such woods preserved.”

In 1912, landscape architect Edward H. Bennett seconded Olmsted’s opinion. Portland’s Civic Improvement League hired Bennett, who had earned professional accolades for collaborating on the Chicago Plan in 1909, to create a plan for Portland’s physical development. Among his recommendations in the Greater Portland Plan, Bennett opined that “woodland areas are the great life-giving elements in the City” and advised that Portland establish a forest reserve, because the forested land would “form delightful incidents of a ride, walk or drive over the hills.”

Portlanders, however, were not yet ready to make the hills into a park. Timbered land in the Tuality Mountains, as the hills were sometimes called, provided construction material for the growing cities of Portland and Linnton. The land also provided an income for some landowners who logged their property extensively. As a result, only sparse tree coverage remained in some areas, and most of today’s Forest Park is made up of second-growth trees.

The Forest Park acreage also was sought after for its views and its potential for housing development, although developers’ attempts to terrace the steep hillsides in the early 1900s left the land unstable for housing. In the 1920s, efforts to establish housing in the higher elevations of Forest Park failed when developers underestimated fees for building Leif Erickson Drive. Known as Hillside Drive until it was renamed in 1933, the road was graded in 1914 and followed the ridgeline from Germantown Road down to Portland on the south side. Hillside Drive was heralded for its potential to open the forested land for development, but high construction and maintenance fees left developers unable to sell the lots when the city increased the tax assessment to fund the roadway. Consequently, hundreds of acres of land along Hillside Drive were turned over to the City of Portland due to unpaid taxes.

More privately owned land was surrendered to the city during the Depression, as some landowners faced foreclosures because they were unable to pay property taxes. By the mid 1930s, up to 2,500 acres of privately held land was returned to city and county ownership through tax foreclosures. Much of the land that would become Forest Park was now publicly owned.

In the 1940s, the recommendations of Robert Moses initiated the first organized effort to convert the land into a park. Moses was a planner who served as New York park commissioner and was a member of the New York City Planning Commission. The Portland Area Postwar Development Committee and shipping magnate Edgar Kaiser hired Moses in 1943 to create a plan to guide the city through the years following World War II.

One of Moses’s recommendations was that the forested land should become a park. Although this was not a new idea, public views on green space and recreation had changed enough by 1944 that the Portland City Club undertook the first formal study of the issue. The land had proven to be too steep for farming, its old growth had already been logged, housing development was not feasible, and attempts to drill for oil had failed. City Club’s conclusion was that the area was unsuitable for anything but parkland, and in 1945 they recommended that the area be set aside as a city park.

To promote the establishment of Forest Park, members from City Club and the Mazamas, along with local politicians, called for the formation of the Forest Park Committee of Fifty. Headed by retired U.S. Forest Service silviculturalist Thornton Munger, the group was comprised of representatives from forty local civic organizations as well as ten “at-large” members, representing organizations that ranged from the Oregon Roadside Council and the Izaak Walton League to the Camp Fire Girls, Woman’s Forum, and Portland Chamber of Commerce.

Through extensive public outreach, the committee lobbied the Portland City Planning Commission to forward the idea of a park to the city council. The city council approved the recommendation in 1947, in large part because there was no significant cost associated with creating the park. Much of the land was publicly owned, and the park was slated to be “unimproved,” meaning it would not include established playgrounds or picnic areas.

The external boundaries of the park were set, encompassing private and county land, in addition to city land. The Multnomah County Commission transferred the county’s acreage to the City of Portland without cost. On September 25, 1948, at a ceremony held at an abandoned oil well, the city formally dedicated Forest Park.

The Committee of Fifty continued to protect and promote the land after the park’s establishment and is now the Forest Park Conservancy. Privately owned land still remains within the park boundaries, though the Portland metropolitan area’s tri-county governing agency, Metro, contributed to land acquisition in and around the park through its Natural Areas Program, ensuring the maintenance of forest coverage and protection of the wildlife corridor.

-

![Before Forest Park was established, it was privately owned (and homesteaded) and logged.]()

Forest Park.

Before Forest Park was established, it was privately owned (and homesteaded) and logged. bb002225 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![Before Forest Park was established, it was privately owned (and homesteaded) and logged.]()

Forest Park.

Before Forest Park was established, it was privately owned (and homesteaded) and logged. bb002225 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

Related Entries

-

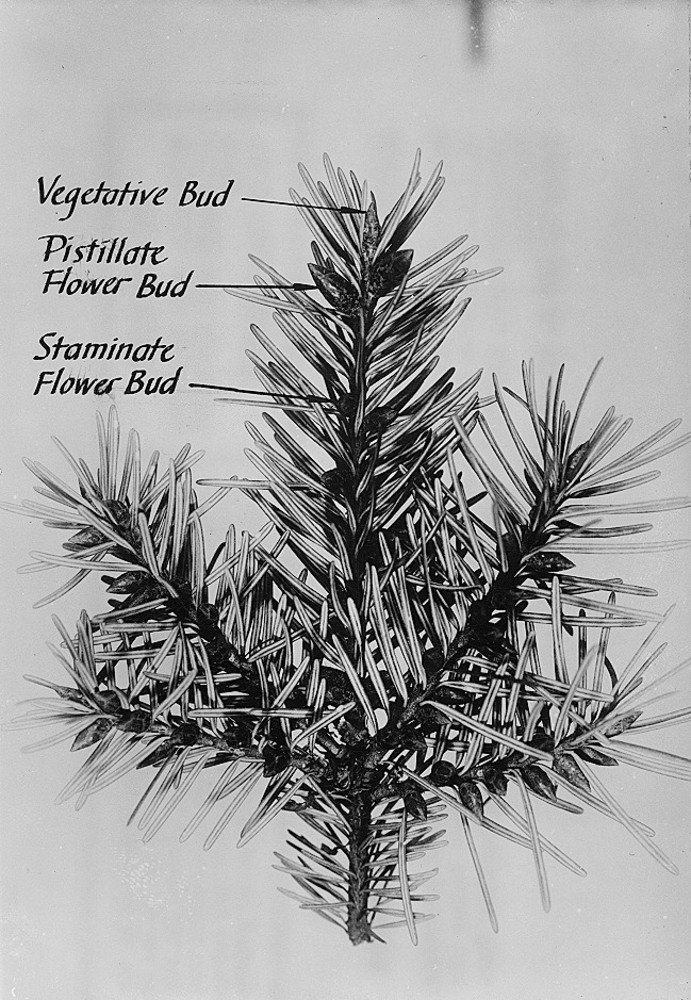

![Douglas-fir]()

Douglas-fir

Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), perhaps the most common tree in Or…

-

![Izaak Walton League in Oregon]()

Izaak Walton League in Oregon

The Izaak Walton League of America (IWLA), nicknamed the "Waltonians," …

-

![Mazamas]()

Mazamas

The history of the Mazamas began in early 1894 when William Gladstone S…

-

![Olmsted Portland Park Plan]()

Olmsted Portland Park Plan

In the late nineteenth century, Portland's City Park (soon to be named …

-

![Western hemlock]()

Western hemlock

Western hemlock, or Alaska-spruce (Tsuga heterophylla), is a common con…

-

![Western red cedar]()

Western red cedar

Western red cedar (Thuja plicata) is one of the grand trees that grows …

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Houle, Marcy Cottrell. One City’s Wilderness. Portland, Ore.: M. C. Houle, 1982.

Munger, Thornton T. History of Portland’s Forest-Park. Portland, Ore.: Committee of Fifty, 1960.

Provost, Elizabeth. "The Genesis of Portland's Forest Park: Evolution of an Urban Wilderness." Master's thesis, Portland State University, 2009.