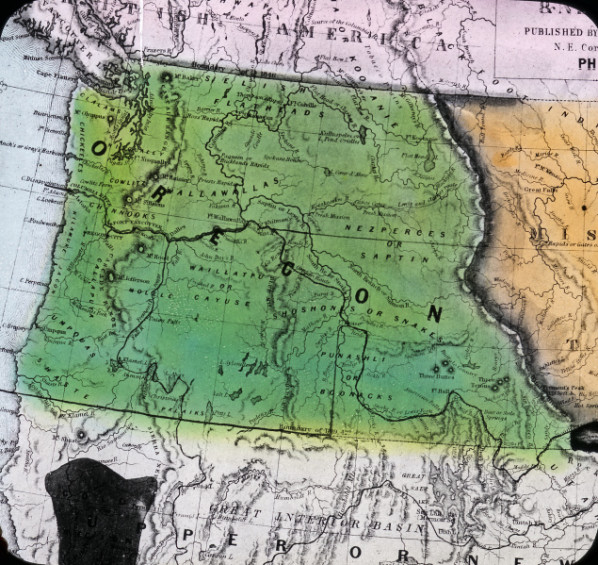

Fort George was the British name for Fort Astoria, the fur post established by the Pacific Fur Company in 1811 on the south bank of the Columbia River, seven miles from the river’s mouth. The fort was a mainstay in British fur trading activity on the lower Columbia River from 1813 to the 1840s, but its history is embedded in the larger competition between Britain and the United States for control of the Columbia River and the Oregon Country.

On November 30, 1813, during the War of 1812, Captain William Black, commanding the HMS Racoon, crossed the Columbia River bar and anchored in Baker Bay on the north side of the river. Within days, Black and an entourage from the Racoon had made their way across the river in the sloop Dolly to Fort Astoria, where the captain intended to capture the American fur post for Great Britain. But Black soon discovered that Fort Astoria could not be a prize of war, because the North West Company, a British firm based in present-day Canada, had purchased the post from the Pacific Fur Company two months earlier.

Nonetheless, Black took possession of the fort on December 12, 1813, renaming it Fort George for his king. He ran up the Union Jack and smashed a bottle of Madeira wine on the flagpole. While the captain’s actions did not alter the ownership of Fort George—it was the property of a private trading company—within a matter of months, the Treaty of Ghent at the end of the War of 1812 further muddied the fort’s legal standing. Article I of the treaty specified that all “territory, places, and possessions whatsoever, taken by either party from the other, during the war…shall be restored without delay.” Was the fort British or American property, and would either nation claim sovereignty over the post?

The United States informed Great Britain that it intended to restore Fort Astoria and sent a warship in late 1817 to the mouth of the Columbia. In July, British officials had warned James Keith, chief factor at Fort George, that Americans planned to restore their control of Astoria. In August 1818, the American ship Ontario, captained by James Biddle, arrived at the mouth of the Columbia and anchored offshore to avoid crossing the dangerous river bar. He piled fifty soldiers into three boats, crossed the bar, and paddled up the Columbia River seven miles to Fort George, which sat on a low bench of land on the river.

Biddle prepared to conduct an official restoration of the fort, but he had no authority. The best he could do was affix a sign to a tree pronouncing that he had taken “possession” of the area “in the name and on the behalf of the United States.” In addition, Americans had nailed another similar sign on the north side of the Columbia. Biddle had impatiently left Valparaiso, Chile, without John B. Prevost, the special agent to Peru and Chile who was tasked with establishing the restoration. Prevost had to hitch a ride to Fort George on a British ship, the Blossom, which arrived at the fort in early October 1818, weeks after Biddle had departed.

Prevost met with Keith and proclaimed the fort restored to American ownership, but he accorded the North West Company time to sort out its affairs. It turned out, however, that the Americans had little interest in occupying the fort and that Britain and the United States had approved the Anglo-American Convention of 1818, which confirmed the North West Company’s ownership of Fort George.

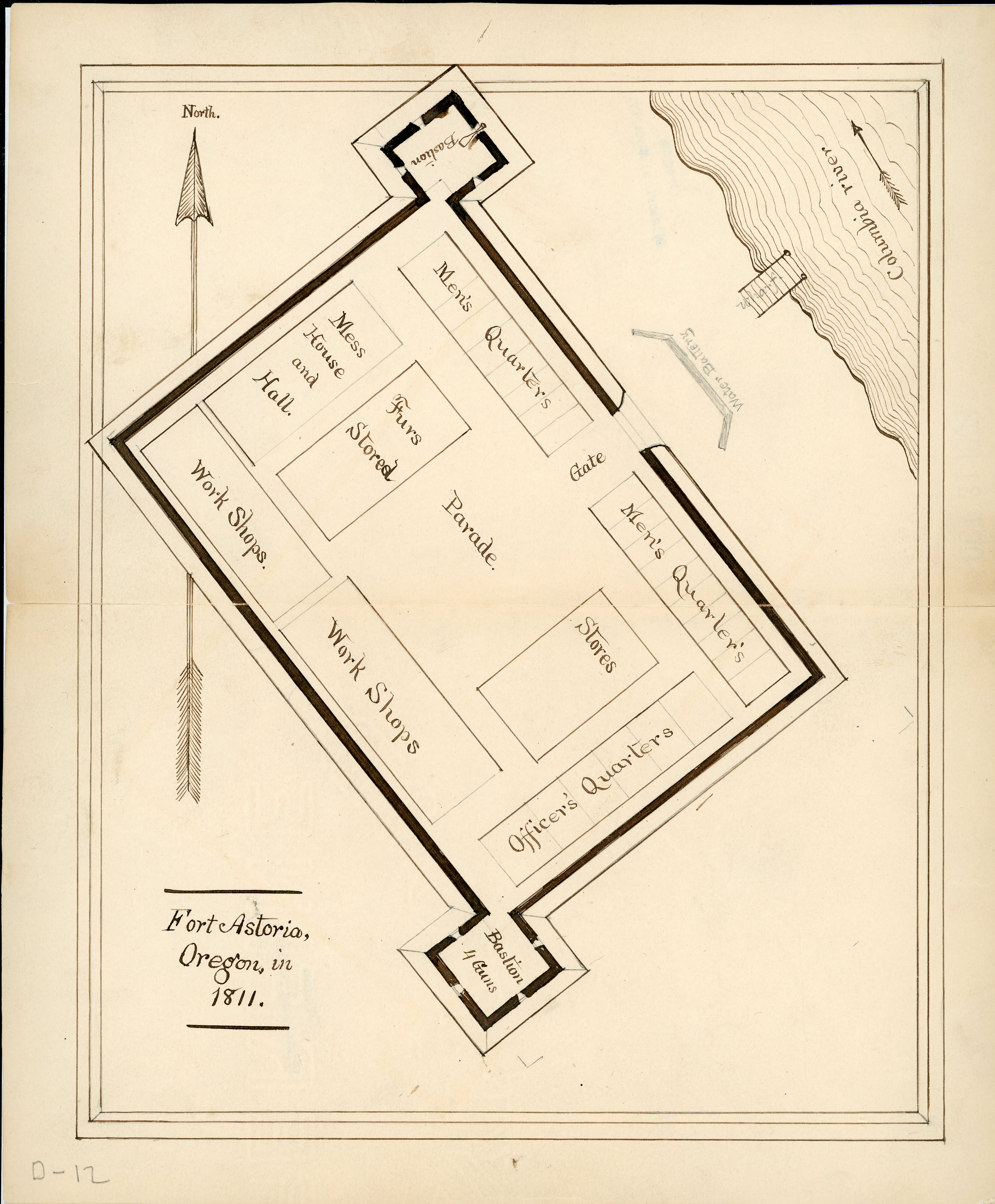

During 1813-1818, the North West Company had expanded the original footprint of Fort Astoria, from 150 by 150 feet to 190 by 210 feet, and had constructed a 170-foot-long warehouse. Fort George was now substantially larger, better armed—six 6-pound cannon, four 4-pound cannon, two 6-pound mortars, and seven swivels—and more solidly built. The fort operated as the collection point for furs harvested in the Columbia Basin interior and as an embarkation point for international shipment. North West Company personnel at Fort Astoria in 1817 stood at 150, nearly all French Canadian, with 30 Hawaiian laborers (Kanakas).

The Hudson’s Bay Company absorbed the North West Company in 1821. Within three years, HBC management had decided to move its Columbia District headquarters upriver to Fort Vancouver, partly because Fort George had only twenty acres available for cultivation and was vulnerable to naval attack. HBC abandoned Fort George for five years, resuscitating it in 1829 as a fishery station and “a small outer depot” that focused on Indian trade on the lower river. Chief factor of the fort, James Birnie, conducted trade with Chinook and Clatsop Indians and made Fort George part of HBC’s dwindling operations on the Columbia into the late 1840s, when the company moved its headquarters to Fort Victoria on Vancouver Island.

In a little over three decades, Fort George had risen and receded as a key outpost of Britain’s fur industry in Oregon, only to languish in the Hudson’s Bay Company's declining fur trade on the Columbia. In 1838, Captain Edward Belcher of the visiting HMS Sulphur provided a description of the post that serves as an epitaph of sorts: “A small house for Mr. Birnie, two or three sheds for the Canadians, about six or eight in number, and a pine stick with a red ensign, now represented Fort George. Not a gun or warlike appearance of any kind remains. One would rather take it for the commencement of a village than any noted fort.”

-

![]()

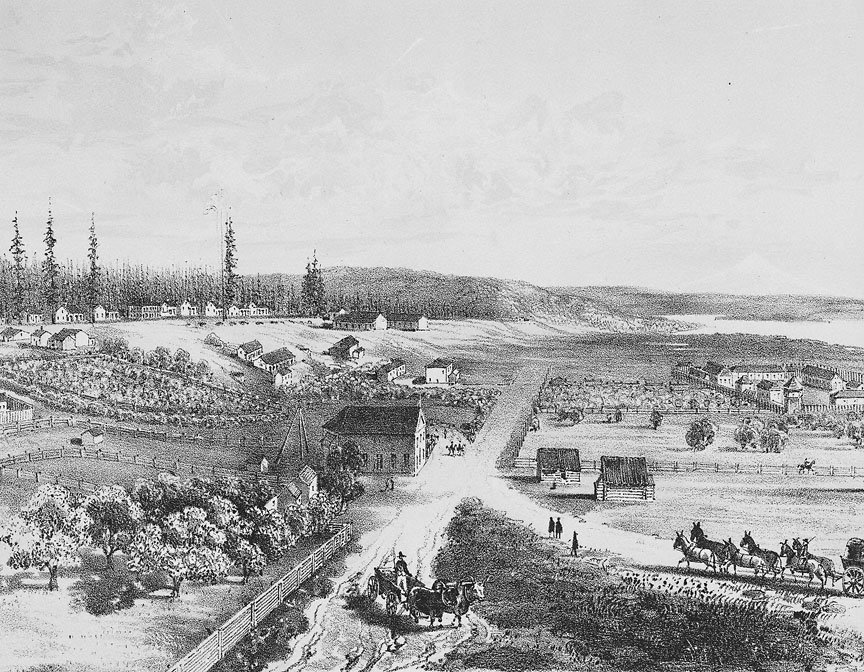

Fort George, drawing by Charles Wilkes, 1841.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 00535

-

![Sketch by H. Warre]()

Fort George, 1845.

Sketch by H. Warre Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 35111

-

![Earliest known illustration of Fort Astoria, by Gabriel Franchere, employed by Astor,]()

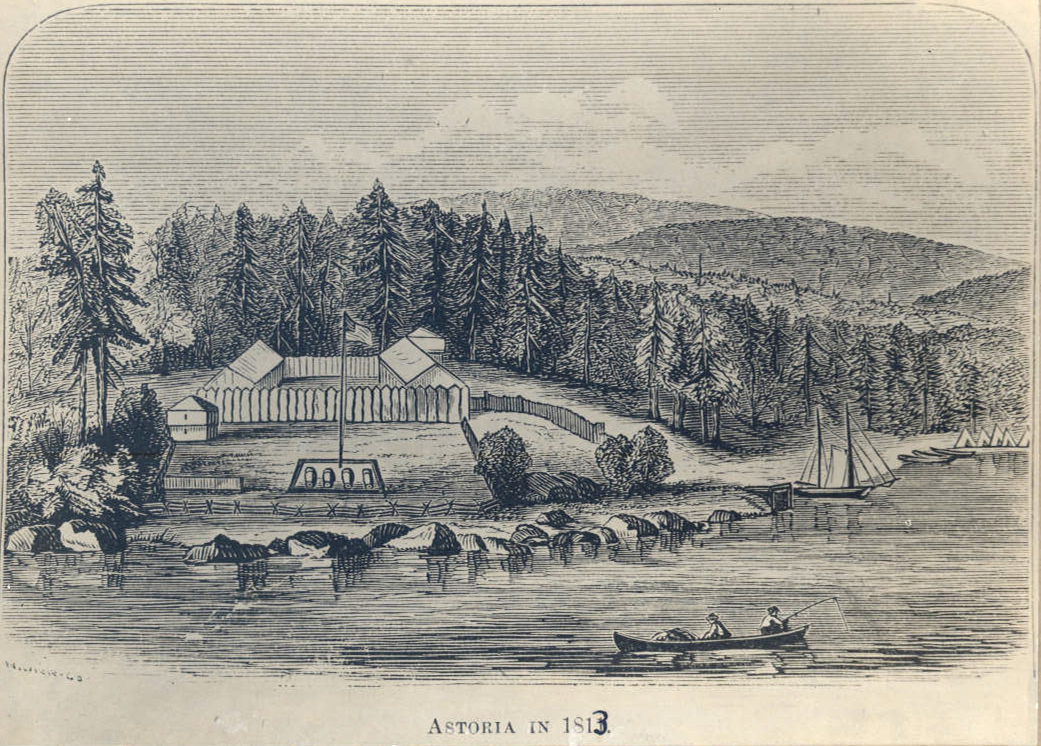

Fort Astoria, 1813.

Earliest known illustration of Fort Astoria, by Gabriel Franchere, employed by Astor, Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi51

Related Entries

-

![Astor Expedition (1810-1813)]()

Astor Expedition (1810-1813)

The Astor Expedition was a grand, two-pronged mission, involving scores…

-

![Columbia River]()

Columbia River

The River For more than ten millennia, the Columbia River has been the…

-

![Fur Trade in Oregon Country]()

Fur Trade in Oregon Country

The fur trade was the earliest and longest-enduring economic enterprise…

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

-

![Oregon Question]()

Oregon Question

“The Oregon boundary question,” historian Frederick Merk concluded, “wa…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Keith, Lloyd, and John C. Jackson. The Fur Trade Gamble. Pullman: Washinton State Univ. Press, 2016.

Franchere, Gabriel. A Voyage to the Northwest Coast of America. New York: Citadel Press, 1968.

Mackie, Richard. Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British fur Trade on the Pacific 1793-1843, Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997.

Koppel, Tom. Kanaka: The Untold Story of Hawaiian Pioneers in British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest. Vancouver, B.C.: Whitecap Books, 1995.

Belcher, Captain Sir Edward. Narrative of a Voyage Round the World, performed in Her Majesty’s Ship Sulphur, during the years 1836-1842. London: Henry Colburn Pub., 1843.