Dick Fosbury changed the high jump forever when he won a gold medal at the 1968 Olympic Games using a new style of his own invention. Fosbury won and set a new Olympic record of 7 feet, 4¼ inches using a style he had created as a teenager. Although coaches and others initially labeled Fosbury’s unique style as “goofy” and dangerous, the Fosbury Flop became the standard technique of nearly all competitive high jumpers.

Richard Douglas Fosbury was born in Portland on March 6, 1947. After his family moved to Medford in 1954, he became interested in the high jump in grade school. When he started jumping, he learned a style called the scissors, which requires a jumper to kick the lead outer leg above the height of the bar, throw the trailing leg across the bar, and land on his feet. By the time Fosbury was in high school, the scissors was being supplanted by the more popular straddle style, in which the jumper plants his inner foot, drives his outer leg up, and rolls belly down over the bar.

Fosbury was not an outstanding jumper at Medford High School, and his coach, Dean Benson, encouraged him to abandon the scissors in favor of the straddle. But Fosbury was dissatisfied with his progress, and he began to develop his own style during his sophomore year. At a high school meet in Grants Pass that year, he barely cleared the bar at 5 feet, 4 inches, and he knew he needed to try something different to stay in the competition. Frustrated, he decided to modify the scissors jump by taking off on his outside foot and going over the bar backwards, dropping his shoulders over the bar and raising his hips and butt. The technique worked, and Fosbury cleared 5 feet, 10 inches, six inches higher than his personal record.

Fosbury later called his new style the Flop after a Medford Mail photo caption compared him to a “fish flopping in a boat.” As a senior at Medford High, Fosbury broke the school record, placed second at state, and won a regional and a national meet. Although other athletes developed a style similar to Fosbury’s, he had come to the one he used on his own. The Flop is efficient, because the jumper does not raise his center of gravity above the bar. Instead, his head goes over the bar first, followed by his torso. As long as the jumper kicks his feet over at the right time, the center of gravity remains below the bar, requiring less lift to cross it.

When Fosbury attended Oregon State University on a track scholarship, Coach Berny Wagner insisted that he practice the straddle, a conventional style of high jump the young jumper had learned in high school. The coach allowed Fosbury to use the Flop at track meets, however, to score team points, and Fosbury eventually dropped conventional jumping styles and focused on the Flop. As a sophomore, he broke the OSU high jump record, clearing 6 feet, 10 inches, and he won NCAA titles in 1968 and 1969.

The 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City took place during a time of unrest in the United States. The war in Vietnam was becoming increasingly unpopular in America, especially among young people, many of whom worried about the draft. Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy had been assassinated earlier that year, and protesters and police clashed at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. At the Olympics, American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos, both African Americans, placed first and third in their event. Standing on the medal podium, each donned a single black glove and raised a fist to protest racial injustice. The crowd booed, and the U.S. Olympic Committee immediately sent the two athletes back to the United States. When Fosbury stood on the podium to receive his gold medal, he flashed a peace sign and raised his fist in support of Smith and Carlos. He was neither booed nor sent home.

After Fosbury’s success at the Olympic Games, U.S. Olympic track and field coach Payton Jordan cautioned him against the Flop. “Kids have a tendency to emulate champions,” he said, “and I hope that Dick’s wonderful victory doesn’t start a trend. If it does he’s liable to wipe out an entire generation of high jumpers. They’ll all have broken necks.” Some doctors worried about the Flop having the same effect. Nevertheless, athletes continued to use the technique. The legions of paralyzed jumpers never materialized something often attributed to improvements in the landing pit. By 1980, thirteen of sixteen high jumpers in the Olympic finals used the Flop.

Fosbury earned an engineering degree from OSU in 1972 and moved to Blaine County, Idaho, where he started Sawtooth Engineering, later named Galena Engineering. He served as the city engineer for Ketcham and Sun Valley and retired from the firm in 2011. Active in the U.S. Olympians Association and the YMCA, he taught at clinics and track camps. In 2018, he was elected to the Blaine County Commission.

Fosbury was inducted into the OSU Hall of Fame, the Oregon Sports Hall of Fame, and the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame. In 2018, on the fiftieth anniversary of his gold medal, Oregon State University erected a statue of Fosbury at the former site of Bell Field, where he had competed as an OSU student. He passed away in March 2023.

-

![]()

Dick Fosbury, 1968.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

![]()

Dick Fosbury, Bell Field, 1969.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

![]()

Coach Berny Wagner and Dick Fosbury, 1968.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

![]()

Dick Fosbury winning Olympic High Jump, Mexico City, 1968.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

![]()

Dick Fosbury with the Oregon Dairy Princess (unnamed), 1969.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Oregon Journal, photo file 411

Related Entries

-

![Fred Milton (1948-2011)]()

Fred Milton (1948-2011)

During a period of social and racial turmoil in the late 1960s, the Bla…

-

![Joni Huntley (1956–)]()

Joni Huntley (1956–)

As a seventeen-year-old senior at Sheridan High School, Joni Huntley be…

-

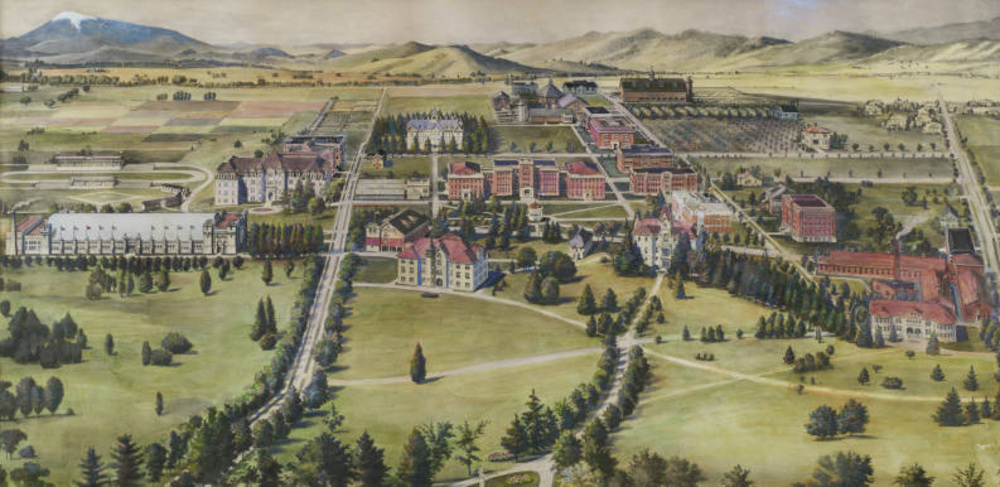

![Oregon State University]()

Oregon State University

Oregon State University (OSU) traces its roots to 1856, when Corvallis …

-

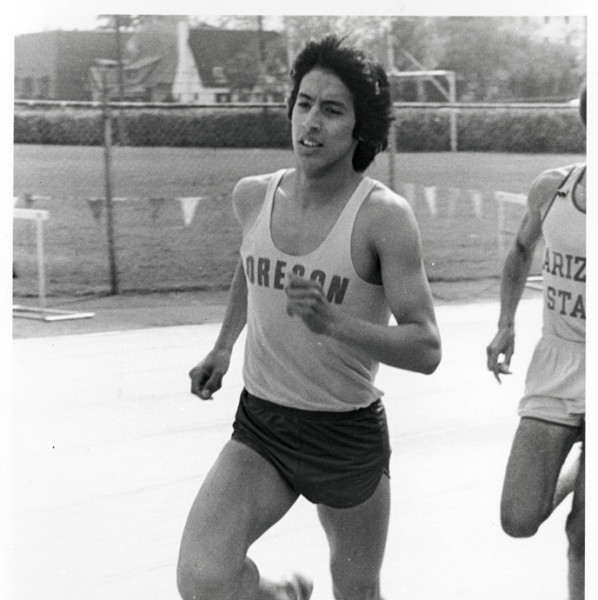

![Rudy Chapa (1957-)]()

Rudy Chapa (1957-)

“Rudy, Rudy,” chanted the fans attending the June 1978 NCAA Track and F…

-

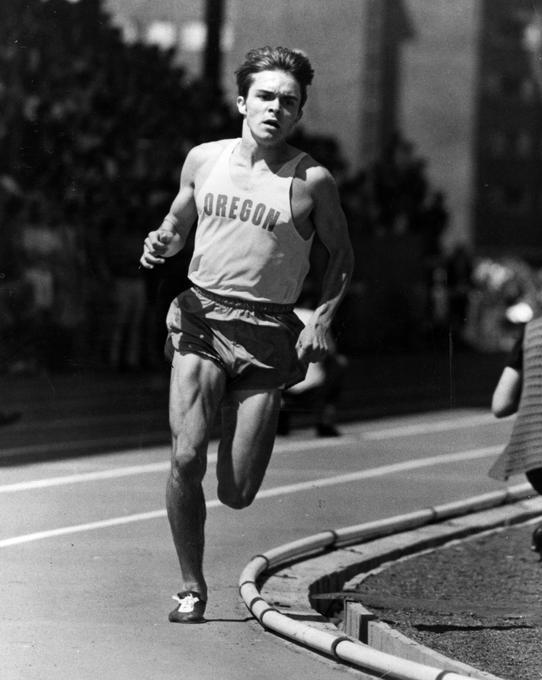

![Steve Prefontaine (1951-1975)]()

Steve Prefontaine (1951-1975)

For Steve Prefontaine, running was a way to find confidence, a way to s…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Dick Fosbury, 1968 Olympics. International Olympic Committee. Videos.

Eggers, Kerry. “From Flop to Smashing High Jump Success.” Portland Tribune Sports, July 22, 2008.

Welch, Bob, with Dick Fosbury. The Wizard of FOZ: Dick Fosbury’s one-Man High-Jump Revolution. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc, 2018.

Miller, Kevin.“Time to Honor OSU’s Golden Rebel.” The Oregon Stater (Fall 2018).

Almond, Elliott. “The Fosbury Flop: Scorned Method is Taking Sport to New Heights.” Los Angeles Times, August 4, 1989.

Raglin, Jeremy. “Dick Fosbury – Acclaimed Olympic Track and Field Athlete.” PDX People.

Faqua, Brad. “Fosbury takes track and field to new heights.” Corvallis Gazette-Times, March 29, 2014. Updated December 22, 2019.

"Floppin Heck." Spikes, November 28, 2014.

Grimsley, Will, "AP was there: Smith and Carlos protest during 1968 Olympics." Washington Times, October 15, 2018.