William Trufant Foster was the first president of Reed College, which was founded in Portland in 1908. Under his leadership, Reed instituted policies and practices that became the foundation of the liberal arts college, including an emphasis on academic excellence; not releasing grades to students; a required senior thesis and oral exam; no fraternities, sororities, or intercollegiate athletics; and the honor principle. Foster was also chancellor of Los Angeles public schools and the director of the Pollak Foundation for Economic Research in Newton, Massachusetts.

Foster was born in Boston on January 18, 1879. His father, who had spent time in a Confederate prisoner-of-war camp, died before Foster was two. By the time he graduated from Roxbury High School, he was supporting himself, and he entered Harvard College at age seventeen. Foster studied English and argumentation and was a member of the debating club, graduating in 1901. He then taught at Bates College in Lewiston, Maine, before returning to Harvard, where he earned a master’s degree in English in 1904.

Appointed as an instructor in English and argumentation at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, Foster proved to be an outstanding teacher and administrator. Before long, he was promoted and became the youngest full professor in New England. His work appeared in professional journals and in periodicals such as The Nation, and in 1907 he published a popular textbook, Argumentation and Debating, which provided him some financial security. He married Bessie Lucile Russell, a former Bates student, in December 1905. The couple had four children.

From October 1909 to June 1910, Foster studied at Teachers College, Columbia University, completing the courses required for the PhD. Influenced by John Dewey and Dewey's philosophy—which emphasized experiential education, the development of a student's full capacities, and the importance of education in social reform—Foster’s dissertation, The Administration of the College Curriculum, placed the blame for the small amount of intellectual enthusiasm among students on college administration. He proposed remedial solutions and concluded with a sub-chapter, “The Ideal College,” which became the blueprint for the founding of Reed College. Foster received his PhD in 1911.

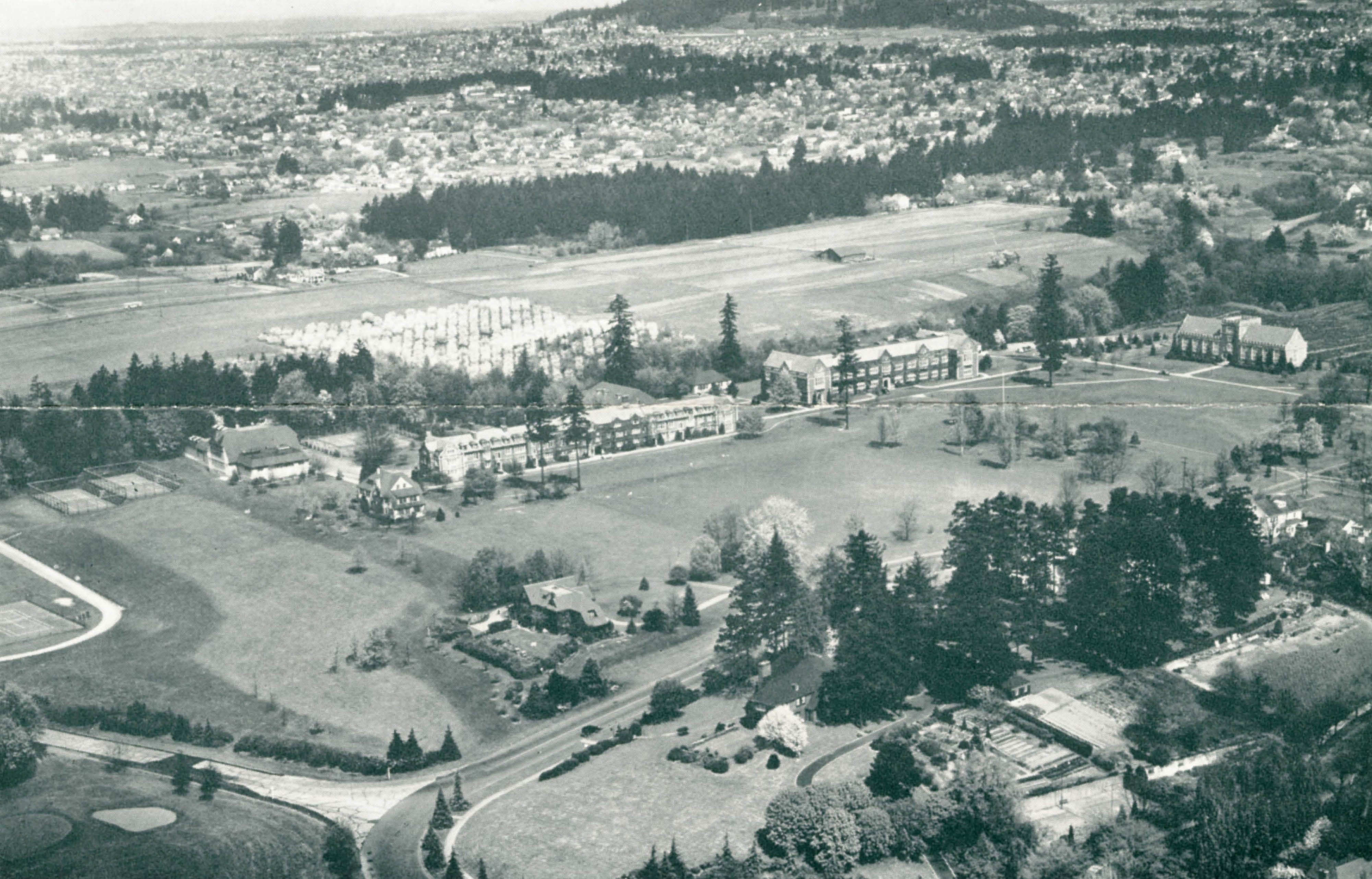

Foster was recommended to the Board of Trustees of the Reed Institute by several nationally recognized leaders in higher education as a strong candidate to be the first president of the liberal arts college they were establishing. Assuming the position on August 1, 1910, at the age of thirty-one, he worked with the trustees and architect Albert E. Doyle to plan the first campus buildings, assembled the first faculty, and admitted the first freshman class. In September 1911, the first classes convened in a building on Southeast Eleventh Avenue and Jefferson Street. A year later, students and faculty moved into the Arts Building (now Eliot Hall) and the dormitory (now the Old Dorm Block) on the Eastmoreland campus.

Foster’s vision of the “ideal college” shaped both the academic atmosphere and the community culture of Reed, but financial difficulties and internal and external controversies led to his resignation in 1919. The college’s initial endowment, which consisted mainly of commercial property, did not generate sufficient funds to support the college. As a result, some faculty left for better-paying jobs, and those who stayed were unhappy with Foster’s leadership. The trustees lost confidence in him. In addition, Foster’s strong personality and his outspoken pacifism had alienated important members of the Portland community. He began to suffer from poor health.

After serving briefly as chancellor of the Los Angeles public schools, Foster returned to the Boston area in 1920, when he was named director of the Pollack Foundation, established by his Harvard classmate, investment banker Waddill Catchings. In a series of books published during the 1920s, Foster and Catchings promulgated their heterodox monetary theories, which are considered to be precursors to Keynesian economics. Foster also served on the Consumers Advisory Board of the National Recovery Administration (1933–1935), on the recommendation of Paul Douglas, who was an economics professor at the University of Chicago and an economic advisor to Franklin Roosevelt. Douglas, who was a U.S. senator from Illinois from 1948 to 1966, had been one of Foster’s students and briefly a member of the Reed faculty during his presidency.

Foster returned to Reed College in 1948 to deliver the commencement address and to receive an honorary degree. He died at his home in Jaffrey, New Hampshire, on October 8, 1950. The following summer, Bessie Foster carried his ashes to Portland, where F. L. Griffin, the first faculty member Foster had recruited, scattered them in Reed Canyon.

-

![]()

William T. Foster, 1917..

Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Harris & Ewing Collection

-

![]()

William T. Foster handing out diplomas to Reed graduates in 1915..

Courtesy Special Collections and Archives, Eric V. Hauser Memorial Library, Reed College

-

![William T. Foster looks over the Reed site, 1910]()

William T. Foster, 1910.

William T. Foster looks over the Reed site, 1910 Courtesy Special Collections, Eric V. Hauser Memorial Library, Reed College

-

![Printed in the Reed Magazine, 1986]()

Photo of Foster with faculty in 1913-1914 and excerpts from his statement on "The Ideal College.".

Printed in the Reed Magazine, 1986 Courtesy Special Collections and Archives, Eric V. Hauser Memorial Library, Reed College

Related Entries

-

![Albert E. Doyle (1877-1928)]()

Albert E. Doyle (1877-1928)

Albert Ernest Doyle was one of Portland’s most successful early twentie…

-

![Arthur F. Scott (1898–1982)]()

Arthur F. Scott (1898–1982)

Arthur Frederick Scott, known as Scotty, was a distinguished member of …

-

![Dorothy Olga Johansen (1904-1999)]()

Dorothy Olga Johansen (1904-1999)

Dorothy Olga Johansen was a prominent Pacific Northwest historian and e…

-

![Ernest Boyd "E. B." MacNaughton (1880–1960)]()

Ernest Boyd "E. B." MacNaughton (1880–1960)

E. B. MacNaughton was one of Portland’s most prominent citizens during …

-

![Lloyd Reynolds (1902–1978)]()

Lloyd Reynolds (1902–1978)

Lloyd Reynolds is an iconic figure in Pacific Northwest calligraphy. He…

-

![Reed College]()

Reed College

Situated on 116 acres in southeast Portland, Reed College enrolls nearl…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Sheehy, J. Comrades of the Quest: An Oral History of Reed College. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2012.

Sheehy, J. “What’s so funny ‘bout communism, atheism, and free love?” Reed (Summer 2007), accessed July 13, 2020.

Foster, W. T. “Pay The Price and Take It: Commencement Address." Reed College Bulletin 27.1 (1948). Accessed July 13, 2020.

Dimand, R.W. "William Trufant Foster.” In New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, Second Edition, 2008.