Benjamin Arthur Gifford was one of Oregon’s most prolific commercial landscape photographers during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. From 1888 until his retirement in 1920, he was nationally known for his large-format, often hand-colored photographs of the Columbia River and its towns and people. Gifford, curator and photographer Terry Toedtemeier wrote, "produced the most comprehensive visual record of the Columbia Gorge—and indeed of the entire state of Oregon—that exists from the early twentieth century.”

Born in DuPage County, Illinois, on November 11, 1859, Gifford left home in 1880 and briefly attended the Kansas Normal School in Emporia. He worked for two years as a photographer’s apprentice in Fort Scott before finishing his apprenticeship work in Sedalia, Missouri, with photographer William Latour. In about 1880, he opened Tresslar & Gifford photography studio in Fort Scott with photographer and partner Elkanah P. Tresslar (1847–1916). Two years later, he sold his share of the business and relocated to Chetopa, Kansas, where he ran his own studio for several years.

Gifford married Myrtle Louise Peck (1861–1919) in 1884 in Bourbon County, Kansas. In the summer of 1888, the couple moved to Portland, and by 1891 Gifford was operating a successful photography studio at Sixth Avenue and Morrison Street, across from the Portland Hotel. The Panic of 1893 forced Gifford to move his business to his home on Corbett Street, where he improved on his techniques. By his own account, he was the first photographer in the city to make enlargements using an electric bulb rather than natural light sources, allowing him to make large-format prints indoors at any time of day and regardless of weather conditions.

In 1894, Gifford partnered with Herbert Hale, a local photographer with a strong background in landscape photography. With Gifford's enlargement set-up and printing mastery, the Gifford & Hale studio, for a brief period, had a near monopoly on locally produced large-format prints and murals. The same year, the Giffords’ only child was born, Ralph I. Gifford (1894–1947), who would become a photographer and filmmaker.

In 1896, journalist William Gladstone Steel invited Gifford to join and photograph an expedition to Crater Lake as part of his campaign to promote the lake and its surroundings as a national park. Gifford's photographs from the expedition were published in several newspapers and magazines. That work may have inspired the next phase of his career in which he focused on the commercial possibilities of his photographs for advertising and marketing.

When Gifford’s partnership with Hale dissolved in 1897 or 1898, he moved his family to The Dalles so he could more closely photograph the Columbia River, especially nearby Native communities. He began making photogravure reproductions of his images, sold both as sets of loose prints and in books, and produced hand-colored photo murals for train stations and schools. That work, with its bold colors and romantic aesthetic, was aimed at marketing a picturesque vision of the Columbia River Gorge. Railroads such as the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company bought his landscape images to advertise the region's potential for settlement and tourism, and tourists bought his lithographed and photo postcards as souvenirs of their travels.

While maintaining his home and studio in The Dalles, Gifford opened a studio in Portland in 1901 with his colorist and business manager Violet Kent. He eventually sold that studio to local photographer Charles Y. Lamb and moved his family to Portland in 1910 so he could be closer to his primary clients: railroads. He partnered with Arthur M. Prentiss in 1917 to form Gifford & Prentiss Studio. Gifford’s most notable work during this time was a series of photographs of the construction of the Columbia River Highway, which were exhibited at the 1915 Panama Pacific Exposition in San Francisco.

Myrtle Peck Gifford died in 1919 after a long illness. In October of that year, Benjamin Gifford married Rachel Morgan (1877–1973), a former schoolteacher from The Dalles who had worked for him as a colorist in 1912 and was secretary of Gifford & Prentiss. He retired in 1920, and the couple moved to a rustic log cabin in Salmon Creek, Washington, which they named Wa-ne-ka after one of Gifford’s most famous photographs of the sun setting over the Columbia. Ralph Gifford took over his father’s business in Portland.

Benjamin Gifford died on March 5, 1936. He was buried in Lincoln Memorial Park (now Mount Scott Park Cemetery) in Portland, and his gravestone bears the signature that appears on all of his published photographs. Major collections of Gifford’s photographs are held by the Oregon Historical Society and Oregon State University. His work, reproduced as high-quality photogravures, appear in his books: Snap Shots on the Columbia (1902), Art Work of the State of Oregon (1909), and Art Work of Portland, Mt. Hood and the Columbia River (1912).

-

![]()

Benjamin Gifford, c.1920.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

![]()

Benjamin Gifford, 1910.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

![]()

Benjamin Gifford, 1900.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

![]()

Benjamin Gifford; the boy is likely his son Ralph, 1910.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

![]()

Benjamin Gifford, with camera.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

![]()

Working in the Farm Fields, by Benjamin Gifford, c.1910.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Org. Lot 78, B5 f7 -

![]()

Celilo Falls, by Benjamin Giffford, c.1902.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Org. Lot 78 B2 f6

Related Entries

-

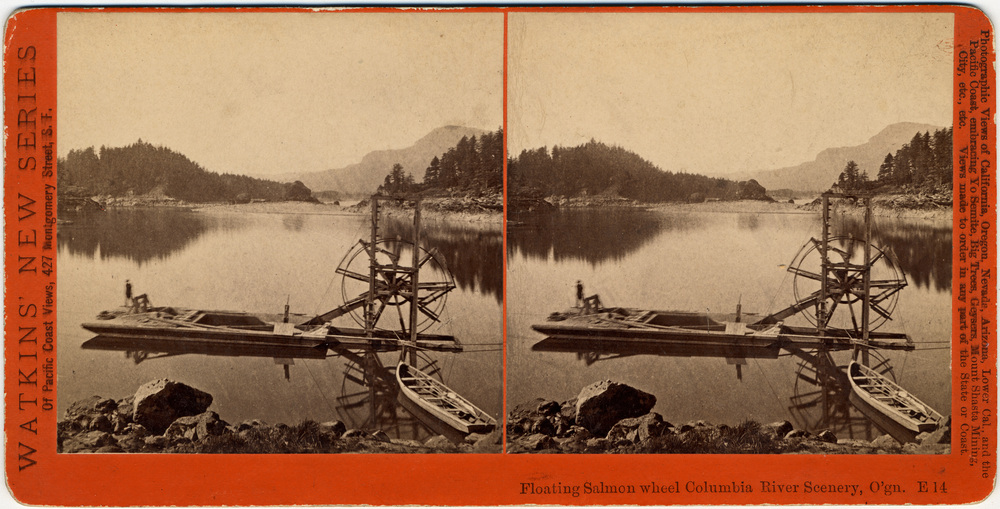

![Carleton Emmons Watkins (1829-1916)]()

Carleton Emmons Watkins (1829-1916)

Carleton Emmons Watkins was a prominent San Francisco-based photographe…

-

![Columbia River]()

Columbia River

The River For more than ten millennia, the Columbia River has been the…

-

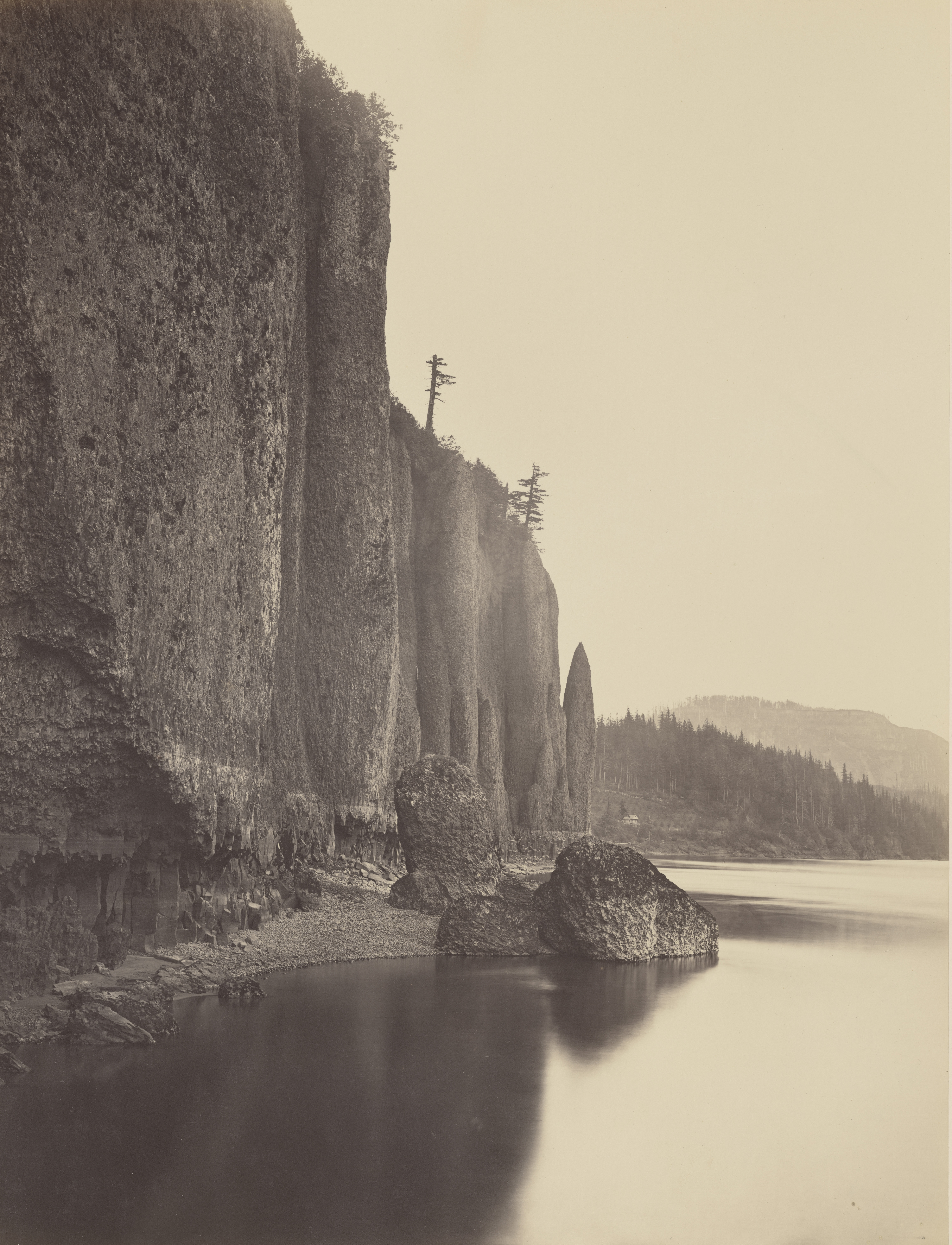

![Columbia River Gorge]()

Columbia River Gorge

The Columbia River Gorge is a striking natural landscape of mountains, …

-

![Lily Edith White (1866-1944)]()

Lily Edith White (1866-1944)

Photographer Lily White once professed: "Alone—controlling the power, d…

-

![Ralph Gifford (1894–1947)]()

Ralph Gifford (1894–1947)

As the Oregon State Highway Department’s first staff photographer, Ralp…

-

![Terry Toedtemeier (1947–2008)]()

Terry Toedtemeier (1947–2008)

Terry Norman Toedtemeier was an Oregon photographer known for his image…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

"B.A. Gifford, Photographic Pioneer, Dies." Oregon Daily Journal, March 6, 1936, 8.

"Artist Gifford Taken by Death." Oregonian, March 6, 1936, 7.

Brown, Robert O. Nineteenth Century Portland, Oregon Photographers: A Collector's Handbook. Portland, Ore.: R. O. Brown, 1991.

Howe, Sharon M. "Photography and the Making of Crater Lake National Park." Oregon Historical Quarterly 103.1 (Spring 2002): 76-97.

Lockley, Fred. “Impressions and Observations of the Journal Man.” Oregon Journal, August 28, 1929.

Toedtemeier, Terry, and John Laursen, Wild Beauty: Photographs of the Columbia River Gorge, 1867–1957. Portland: The Northwest Photography Archive and Oregon State University Press, 2008.