Neil Edward Goldschmidt, the thirty-third governor of Oregon (1986-1991), U.S. secretary of transportation under President Jimmy Carter (1979-1981), and the forty-first mayor of Portland (1973-1979), was one of the most influential, yet controversial figures in Oregon's political history. As the youngest mayor of a major American city in 1973, Goldschmidt was a rising national political star. It is likely that he would be regarded as one of the most charismatic and successful political figures of Oregon's twentieth century if it had not been revealed that he had sexually abused a minor during his first term as mayor, and then covered it up.

Born in Eugene on June 16, 1940, Goldschmidt attended the University of Oregon, where he served as student body president before graduating in 1963 with a bachelor's degree in political science. He earned a law degree from the University of California at Berkeley in 1967.

Goldschmidt was best defined, colleagues say, for his ability to build consensus among rivals in support of his public policies. As a Portland City Council member (1970-1972) and later as mayor, he was the driving force behind the revitalization of the city's downtown—an undertaking that made Portland a model for cities across the nation, many of which were losing their downtown identities to crime, infrastructure decay, and the flight of middle-income families to the suburbs.

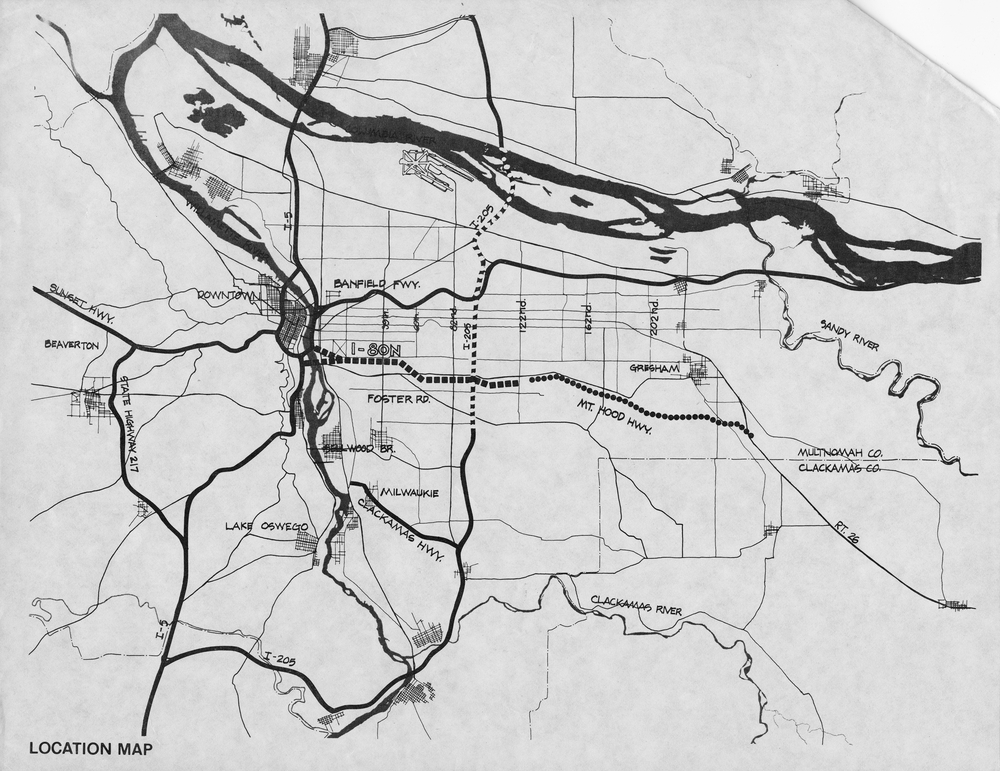

In opposing construction of the Mount Hood Freeway, which would have given people new reasons to bypass downtown connections, Goldschmidt built consensus among labor unions, business interests, and neighborhood groups to divert federal funds for the freeway to finance a modern mass transit system (the MAX Light Rail line and the Portland Transit Mall). He also opened up city government, which had been ruled by an "old-boy" network, to neighborhood activists and minorities.

In 1979, President Jimmy Carter appointed him as the nation's sixth secretary of transportation. Though his tenure was brief, he was the best among Carter's cabinet members in selling the president's agenda during the 1980 presidential campaign against Ronald Reagan. In addition, unlike his predecessor Brock Adams, Goldschmidt's relationships with General Motors, Chrysler, Ford, and American Motors were instructive, not adversarial. Chrysler President and CEO Lee Iacocca, for example, told the Oregonian editorial board that Goldschmidt personally had saved car executives "miles of red tape and wasted time and costs" by organizing one-stop, group meetings with federal officials and agency heads with whom they had business.

As Oregon governor, Goldschmidt was best known for the "Oregon Comeback,” a major multi-agency strategy aimed at bringing the state out of eight years of recession. He instituted regulatory reform and an economic development plan that included repairing the state's infrastructure, including bridges, roads, parks, and prisons. He fulfilled a personal goal by helping create the Oregon Children's Foundation and the Start Making A Reader Today (SMART) literacy program, which put 10,000 volunteers into Oregon schools to read to children.

In 1990, Goldschmidt brokered agreements among business, labor, and insurance interests to change Oregon's workers' compensation regulations. That became a contentious issue in Oregon for years, resulting in lawsuits and efforts by future legislatures to modify the workers' compensation law. His skill in bringing together Democratic liberals and Republican business leaders to support his economic development plan began to wear thin as hard-line liberals accused him of selling out too often to big business. Goldschmidt's cordial relationship with the automobile industry under Carter and a stint as a Nike executive (1980-1985), many liberals argued, changed him.

After leaving elected office, Goldschmidt founded a consulting firm with powerful clients such as Schnitzer Investment, Nike, PacifiCorp, Trail Blazers' owner and Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, and Bechtel Enterprises. His skill as a coalition builder and lobbyist re-established his reputation as the most powerful political figure in Oregon.

It all came tumbling down in May 2004 when reporter Nigel Jaquiss of Willamette Week, a weekly newspaper, published a Pulitzer Prize-winning story about Goldschmidt's sexual abuse of a fourteen-year-old girl who had been the family baby-sitter. The abuse had begun in 1976 and had lasted for several months, according to Goldschmidt in his public confession, and for several years according to the victim. In a public statement he wrote for the Oregonian on February 1, 2011, Goldschmidt said: "In the 35 years since I failed this young woman, her family, and my family, the pain has never eased. There are days when I believe it would be better if I were lifted from this earth and removed as a cause of pain for others and to find quiet for myself."

In 2012, Goldschmidt was living in Portland and France in isolation and disgrace. His portrait was removed from the state capitol. He died from heart failure on June 12, 2024.

-

![Item Number ONLC 00977; Governor Neil Goldschmidt visiting Richmond School and principal Renee Ito-Staub. The governor was instrumental in the implementation of the Japanese Magnet Program in the school.]()

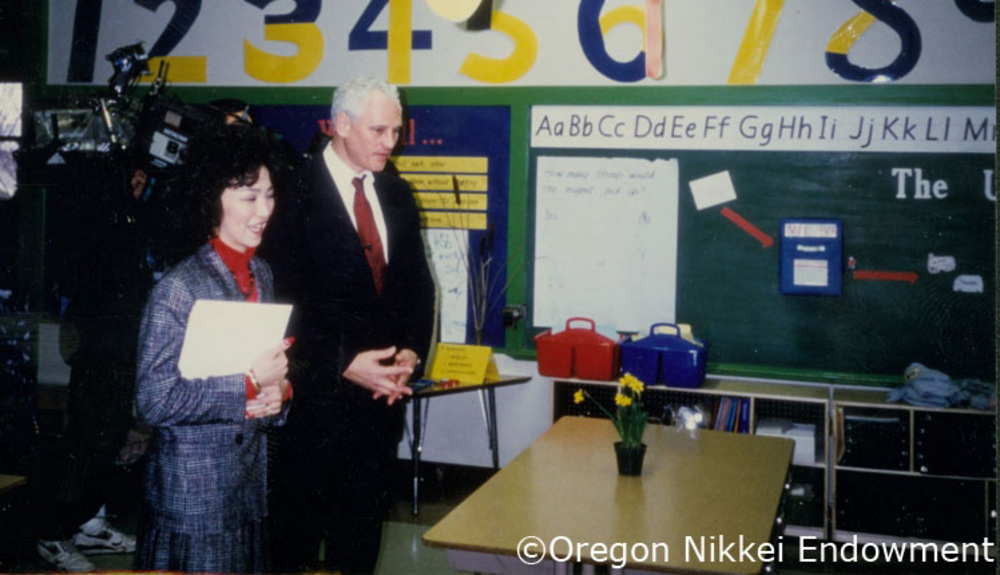

Governor Neil Goldschmidt and principal Renee Ito-Staub at Richmond School in Portland..

Item Number ONLC 00977; Governor Neil Goldschmidt visiting Richmond School and principal Renee Ito-Staub. The governor was instrumental in the implementation of the Japanese Magnet Program in the school. Courtesy of Oregon Nikkei Endowment, gift of Renee Ito-Staub, ONLC 00977

-

![Portrait of Mayor Neil Goldschmidt]()

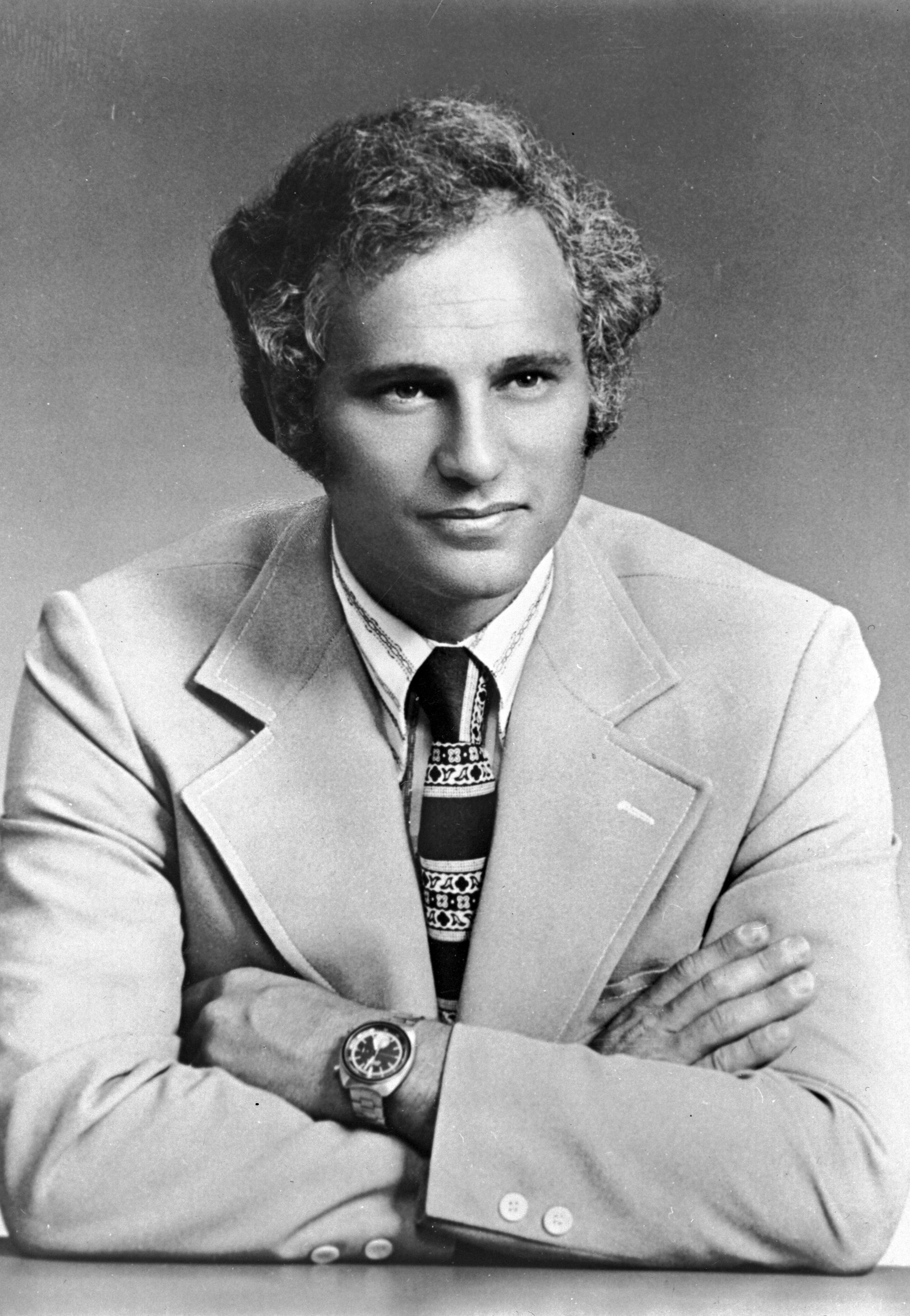

Portrait of Mayor Neil Goldschmidt .

Portrait of Mayor Neil Goldschmidt OrHi 102947 Courtesy Oregon Historical Society

Related Entries

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Buel, Ron. "The Goldschmidt Era." Willamette Week 25th anniversry edition, 1976.

Jaquiss, Nigel. "The 30-year secret." Willamette Week, May 12, 2004.

Lansing, Jewel. Portland: People, Politics, and Power, 1851-2001. Corvallis, Ore.: Oregon State U. Press, 2005.

Wicker, Tom. "Mr. Mayor at 31." New York Times, May 25, 1972.