On July 17, 1856, Washington Territory volunteer soldiers, under the command of Col. Benjamin F. Shaw, swept through a summer village of Walla Walla, Umatilla, and Cayuse families in the meadows along the Grande Ronde River near present-day Summerville and Elgin. The families, who had only a few armed young men, were unprepared for conflict. While they were in the meadows, digging roots and harvesting plants, they suffered a murderous assault by 175 mounted soldiers, who killed at least sixty men, women, and children, the highest casualties of any military-Native conflict in Oregon during the Indian Wars. Sometimes referred to as the Battle of Grande Ronde, the military destruction of the village was a massacre. “The enemy was run on the gallop for 15 miles,” Shaw wrote in his official report, “and most of those who fell were shot with the revolver. It is impossible to state how many of the enemy were killed.”

The attack on the Grande Ronde encampment was part of the war against Yakama bands who had attacked miners and white emigrants east of the Cascade Mountains, an action that prompted Washington Territorial Governor Isaac I. Stevens to order Shaw and his force to hunt down all hostile Native forces. The powerful Yakama chief Kamiakin was Shaw’s preferred target, but Shaw lost patience in the Walla Walla Valley in early July. On learning about the location of a large Cayuse and Walla Walla camp in the Grande Ronde, he hastened to force the Indians onto the reservations agreed to in the 1855 Treaty at Walla Walla.

According to Capt. Walter DeLacy, an officer and diarist in Shaw’s command, when the military first spotted the Indians, a Nez Perce scout was sent to parley with several mounted warriors. Sensing resistance, however, the scout returned, shouting that he had been threatened. Shaw quickly sent his force in pursuit and attacked both Indians on horseback and villagers digging roots. As DeLacy reported, “such was the impetuosity of the charge that many of their women even were unable to escape and were overtaken in the pursuit.”

The mounted Indians scattered to gain safety and defend the village, while others fled on foot. DeLacy could not determine how many Indians had been killed, but he reported that “27 were counted on the ground, and we know of others to the number of 34 that were killed….In this charge we never drew rein for 12 miles. At least 200 packs were scattered over this distance, containing all their winter provisions, furniture, mats and in fact everything they possessed. In returning from the pursuit, we burnt all of these as far as camp….we came to the Indian village, where 120 lodges were counted. It was burnt.” Shaw captured nearly three hundred horses, selected the best, and slaughtered the remainder.

Shaw and Governor Stevens considered it a significant victory, but the consequences of the events in the Grande Ronde Valley did not end military-Native conflict east of the mountains. Nez Perce took the massacre as a warning that voluntary military forces were a threat even to peaceful groups, and tribal leaders divided over whether to enter the Yakima War, with the majority staying neutral.

In addition, the results of Shaw’s raid prompted Stevens to call a second Walla Walla council to persuade tribal leaders to adhere to the provisions of the 1855 treaty as a means to end the war. The council met in early September 1856, but after two days of discussion Stevens had heard enough complaints about unprovoked attacks on Native groups and rejections of the land cessions in the 1855 treaty that he abandoned the talks. For Shaw, he continued to defend the volunteers’ actions throughout his life, though he rarely mentioned the events of July 17–19, 1856, in the Grande Ronde Valley.

-

![]()

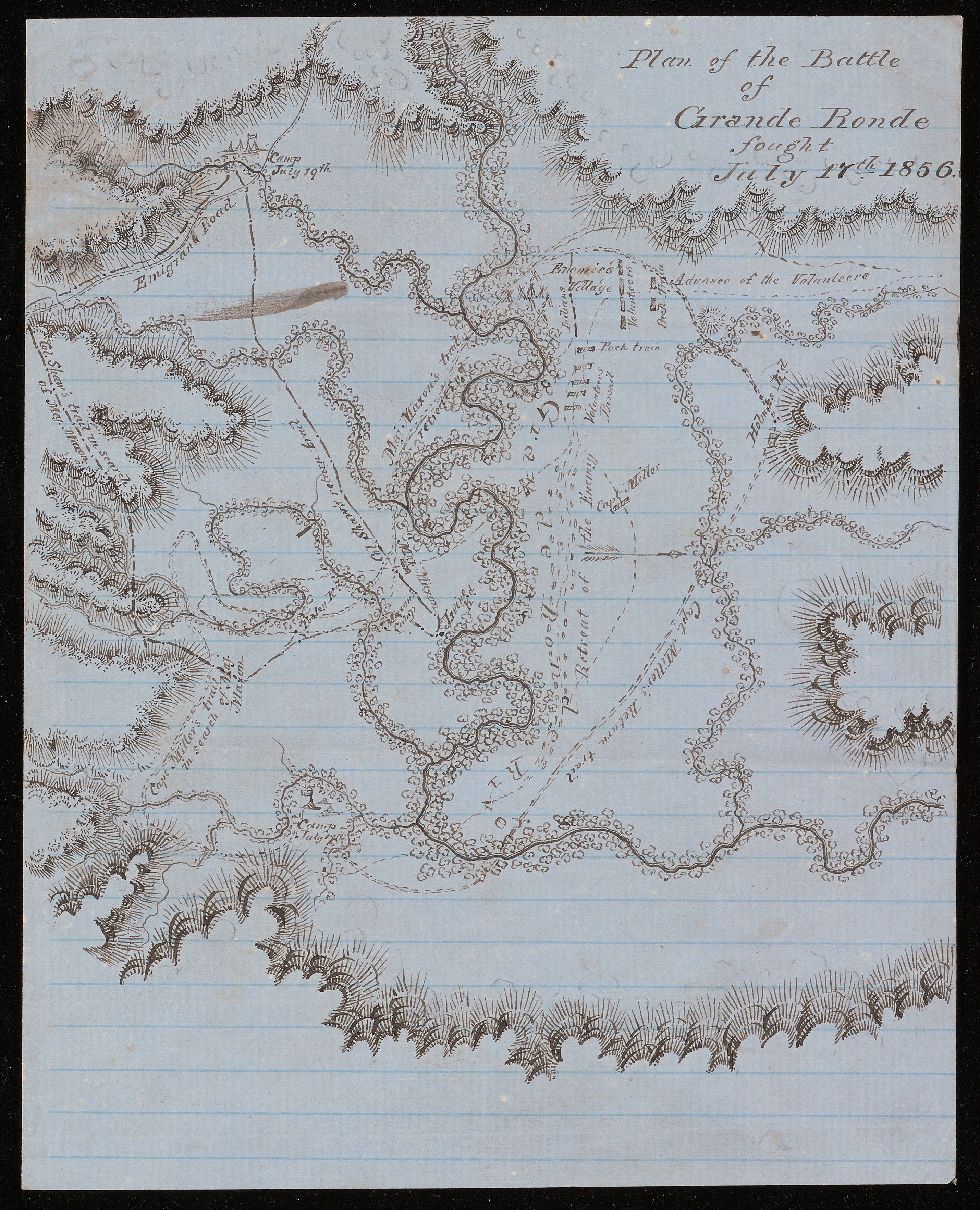

Plan of the battle of Grande Ronde, fought Jul 17, 1856, by W. W. De Lacy.

Courtesy Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library -

![]()

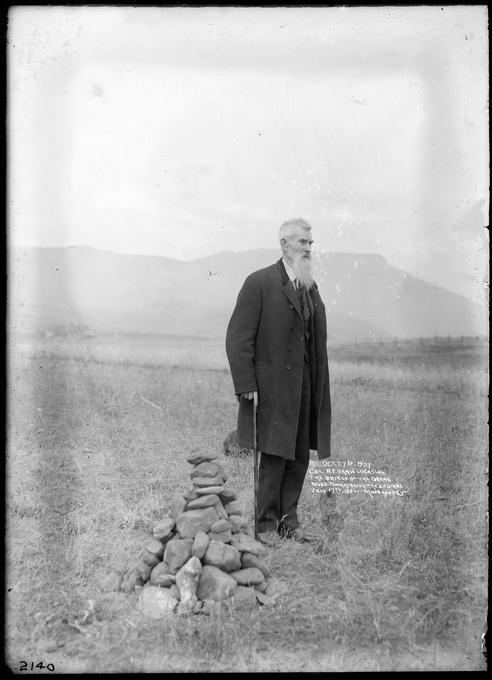

Col. B. F. Shaw locating the site of the massacre at Grande Ronde, 1907.

Courtesy University of Oregon Libraries -

![]()

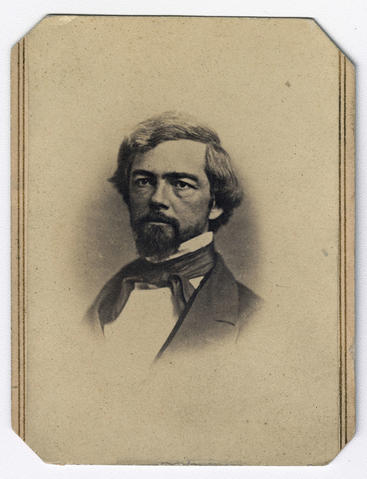

Chief Kamiakin, sketch by Gustavus Sohon, 1855.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi4349

-

![Col. Shaw stands second from the left; George Himes, of the Oregon Historical Society, is third from the right. They were joined by various newspaper editors in 1907 to locate the site of the battle/massacre.]()

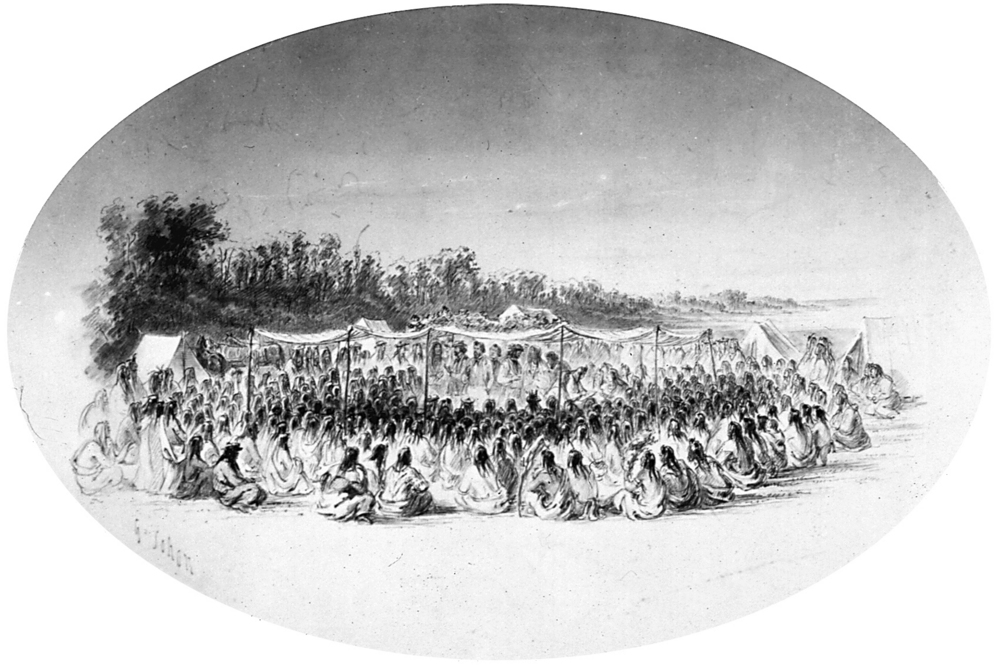

Site of the Indian camp, in the Grande Ronde Valley, attacked by Shaw's forces in 1856.

Col. Shaw stands second from the left; George Himes, of the Oregon Historical Society, is third from the right. They were joined by various newspaper editors in 1907 to locate the site of the battle/massacre. Oregon Historical Society Research Library, photo file 960

-

![]()

-

![Isaac Ingall Stevens.]()

Stevens, Isaac, OrHi 701.

Isaac Ingall Stevens. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., OrHi 701

Related Entries

-

![Benjamin F. Shaw (1829-1908)]()

Benjamin F. Shaw (1829-1908)

During the 1850s, Benjamin Franklin Shaw served as an interpreter for W…

-

![Isaac Ingalls Stevens (1818-1862)]()

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (1818-1862)

Isaac Stevens strode through the Northwest's formative years (1853-1861…

-

![Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855]()

Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855

The treaty council held at Waiilatpu (Place of the Rye Grass) in the Wa…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Richards, Kent D. Isaac I. Stevens: Young Man in a Hurry. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1979.

Josephy, Alvin M., Jr. The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965.

Brown, W. C. The Indian Side of the Story. Spokane, Wash.: C. W. Hill Printing, 1961.