The term “gyppo logging” refers to timber harvesting conducted by small, mobile, independently owned companies that rely on contracts with larger logging firms, sawmills, or timber owners. The origin of “gyppo” remains unclear, though it emerged in early twentieth-century labor conflicts with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in the Pacific Northwest who used the pejorative moniker to identify and disparage small companies that “gypped” their employees on forthcoming salaries, or itinerant (“gypsy”) outfits and workers who sought employment during IWW strikes. Over the years, independent loggers frequently adopted and used the term with pride, though today many prefer the title “contract logger.”

Small logging operators have been around for a long time, harvesting timber from stump ranches and woodlots. But a combination of technological changes, booms in California construction, and new markets for a wider variety of tree species and forest products—particularly after World War II—facilitated a rapid growth of independent loggers in both the Douglas-fir region and the pine forests of western and eastern Oregon.

By the early 1930s, bulldozers enabled the construction of more dirt and gravel roads for use by increasingly common heavy-duty logging trucks with improved braking systems, engines, and tires. This technology of affordable and mobile gas- and diesel-powered machinery began to replace more capital-intensive railroad logging by larger firms, and thus opened opportunities for timber harvesting on steeper and more remote terrain by marginally capitalized loggers who were willing to assume numerous risks, from machinery breakdowns to market downturns to seasonal shutdowns. The emergence of lightweight and efficient chainsaws in the late 1940s further reduced labor costs. During the Depression and continuing into the 1950s, some gyppo operators even ran small, portable sawmills capable of producing rough lumber or specialty items such as shakes, shingles, railroad ties, or box and barrel materials.

Gyppo loggers were generally characterized by their entrepreneurial ambition. As Margaret Elley Felt—the wife of a contract logger who usually worked alongside her husband—once quipped, the gyppo had a “virus of independence in his veins.” They were widely respected for their skills and creativity in maintaining older machinery sold off by larger companies or adapting surplus World War II military equipment for use in the woods. They were also acknowledged for their innovative thinking on high-lead logging techniques, including their use of new self-propelled steel towers and loaders in the 1950s to lift and move cut timber around steep terrain. These skills and strategies helped gyppo loggers take advantage of specific regional settings and evolving forest conditions, markets, and ownership of timber resources.

Gyppos proliferated in the relatively untouched forests of southwestern Oregon after World War II. In some areas, they purchased land or stumpage outright to log; other times they subcontracted through larger timber companies or local mills that owned the timber. Often they reworked land previously logged, taking wood that was merchantable in the expanding pulp and paper market. Gyppos often salvaged damaged timber from blowdowns and forest fires, such as the Tillamook Burn. They also quickly took advantage of emerging markets for hemlock, alder, and smaller second- and third-growth timber. When timber on state and federal lands became increasingly available after 1945, they competed intensely against one another for small sales.

Contributing to the success of gyppo loggers was the small and adaptable nature of their work crews. Most companies had fewer than a dozen employees, many of whom came from an extended family. Women frequently played crucial—and unpaid—roles in the business, doing the bookkeeping, cooking for small company camps, and learning sufficient occupational skills that enabled them to substitute for sick or injured employees. Gyppos tended to avoid joining unions such as the International Woodworkers of America, which formed in 1937; instead, they were socially and economically unified by family, community, religious, and ethnic ties. This included Native American crews working east and west of the Cascades, often logging reservation allotments. Several generations of Coquelle Thompson’s (Upper Coquille/Siletz) family, for example, were representative of this Native woods-working heritage.

The smaller and more intimate character of gyppo logging provided a strong social foundation for an occupational culture that celebrated the values of working-class masculinity, financial independence, the skills of mastering machinery, and knowledge of the natural world useful for both work and subsistence activities, such as hunting, fishing, and berry gathering. The traditions of gyppo life—like much of Northwest logging culture—include a wealth of jokes and anecdotes, cautionary tales, songs, poetry, material art forms, and hunting lore, much of which was expressed in the pages of publications such as Loggers World, created in 1964 by Finley Hays explicitly for the interests of contract loggers.

Numerous autobiographies and biographical accounts of individual gyppo loggers provide insight to the challenges of a profession fraught with physical and financial risks. Occasionally, the attraction to and difficulties of gyppo logging have been represented in popular culture, such as Ken Kesey’s fictional portrait of the defiant Stamper family of coastal Oregon in Sometimes a Great Notion (1964), made into a film in 1970, and in TV reality shows such as Ax Men.

-

![Loggers in Clatsop County]()

Loggers in Clatsop County.

Loggers in Clatsop County Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi93132

-

![]()

Early twentieth-century loggers in Oregon.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Gi8687

-

![]()

Early twentieth-century loggers in Oregon.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., acc28857

-

![]()

Mid-twentieth-century Oregon logger.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., photo file 684-C

-

![]()

Reedport loggers using ferry to get around landslide blocking the highway to the cut site, 1956.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., photo file 684-C

Related Entries

-

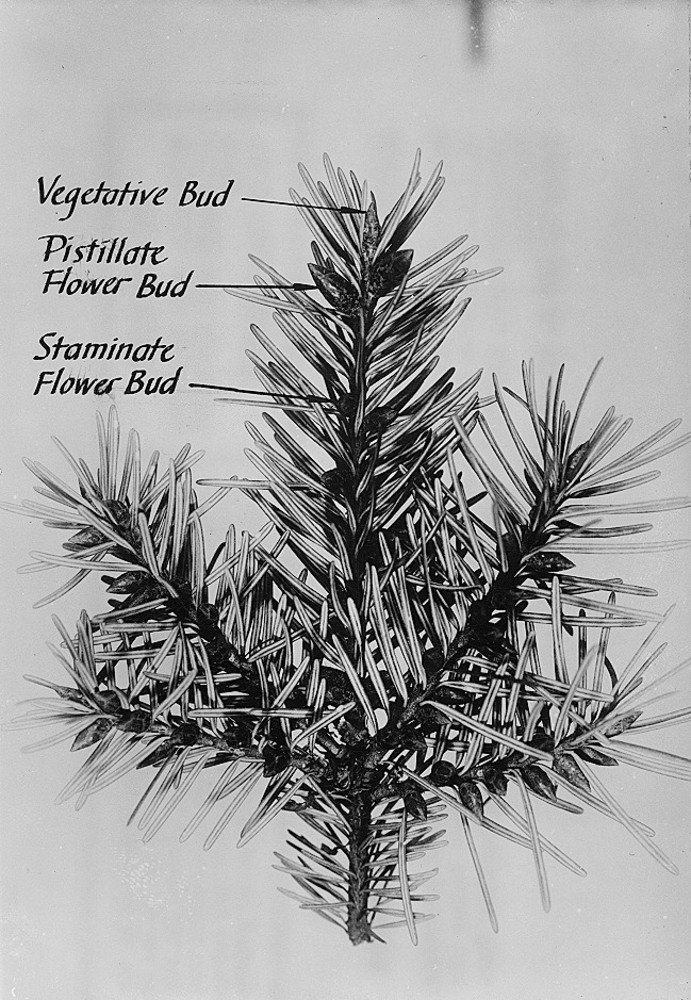

![Douglas-fir]()

Douglas-fir

Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), perhaps the most common tree in Or…

-

![Native American Loggers in Oregon]()

Native American Loggers in Oregon

In pre-settlement times, native peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast …

-

![Timber Industry]()

Timber Industry

Since the 1880s, long before the mythical Paul Bunyan roamed the Northw…

Related Historical Records

Further Reading

Drushka, Ken. Working in the Woods: A History of Logging on the West Coast. Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing, 1992.

Felt, Margaret Elley. Gyppo Logger. (Originally 1963) Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002.

Hall, Joyce M. and Lee Wood. An Oregon Logger Pioneer: George Shroyer’s Life, Work, and Humor. Medford, OR: Reflected Images Publishers, 1998.

Kesey, Ken. Sometimes a Great Notion. New York: Viking Press, 1964.

Robbins, William G. Hard Times in Paradise: Coos Bay, Oregon. (Revised Edition) Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006.

Samuel, A. C. Oregon Logger: Life and Times of A. C. Samuel. Bend, Ore.: Maverick Publications, 1991.

Walls, Robert E. “Lady Loggers and Gyppo Wives: Women and Northwest Logging.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 103.3 (Fall 2002): 362-82.

Youst, Lionel and William R. Seaburg. Coquelle Thompson, Athabascan Witness: A Cultural Biography. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002.