The name Frank T. Hachiya will forever be linked to Oregon’s Hood River Valley, a setting hostile to returning Japanese American servicemen and families at the end of World War II.

Born in the upper valley town of Odell in 1920, Hachiya was a member of the Military Intelligence Service (MIS), translating enemy documents and interrogating prisoners, when he was killed on Leyte Island in the Philippines in January 1945. Caught up in the war in the Pacific after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, Hachiya’s family was scattered—his mother and brother Homer were in Japan, his father Junkichi in the War Relocation Authority camp in Minidoka, Idaho.

Japanese-born Junkichi Hachiya had worked for orchardist Henry Rodamar near Odell until 1936, when the family returned to Japan to take up property Junkichi had inherited. When Junkichi Hachiya returned to the United States in 1940 to follow the fruit harvests, Frank followed, boarding with the Rodamar family and attending Odell High School. He enrolled in Portland’s Multnomah College for a year and in 1941 entered the University of Oregon, where he signed up for political science classes.

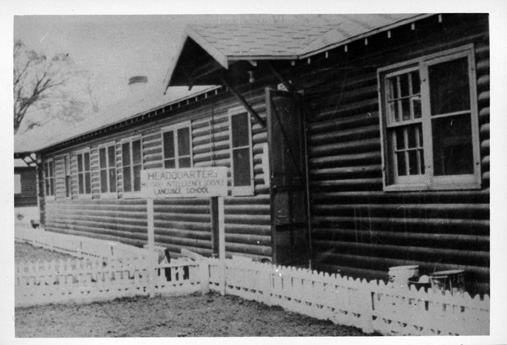

With the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hachiya enlisted in the U.S. Army and enrolled in the Military Intelligence Services Language School at Camp Savage, Minnesota. He served with American forces on Kwajalein and Eniwetok in the Central Pacific. He was a studious person, according to Joseph D. Harrington’s Yankee Samurai, who “took the war seriously” in part because of “what it meant to men like himself, who had twin loyalties”—a reference to his mother and brother who were in Japan.

In his last letter to the Rodamar family, sent from Hawaii where he was taking a brief respite from the battlefront, Hachiya wrote: “Now I have gotten the necessary rest I want to go out again to see the action. The sooner the better.” His decision to cut short his stay in Hawaii took him to Leyte Island to help interrogate Japanese prisoners of war.

When forward units of Hachiya’s troop detained a hostage, the young interpreter volunteered to cross a valley to question him. Moving ahead of his infantry patrol, Hachiya was shot at close range under confusing circumstances, either by a Japanese sniper or by friendly fire. Bleeding profusely, he retraced his steps across the valley to medics, who treated his wounds and sent him to a battlefield hospital.

Hachiya died on January 3, 1945, and was buried in Grave 4479 in the Armed Forces Cemetery on the island. At the end of the war, he was posthumously awarded the Silver Star and the Distinguished Service Cross.

Hachiya’s death coincided with the Hood River American Legion’s removal of the names of sixteen local Japanese American servicemen from the county’s Roll of Honor in early December 1944. The Legion’s action set off a firestorm of criticism in Oregon and across the nation. Although Hachiya’s name was not on the Roll of Honor because he enlisted in the army from an address in Portland, the Oregonian reported his death as “one of the expunged sixteen” and called it an example of Japanese American “gallantry and devotion.” In the wake of nationwide protests, the American Legion’s national commander ordered the Hood River post to restore the names to the county’s Roll of Honor.

Frank Hachiya’s sojourn through Japanese American history did not end on Leyte Island. Monroe Sweetland, an Oregon native and Red Cross supervisor who became friends with Hachiya on Eniwetok, arranged a memorial service in Honolulu in March 1945, with Frank’s MIS colleagues attending. Following the war, Sweetland worked with Ray Yasui of Hood River’s Japanese-American Citizens League and Hachiya’s father, who was living in Illinois, to have Frank’s remains returned to Hood River. In September 1948, Hachiya’s body arrived in Hood River for services at the Asbury Methodist Church. He was reinterred in Idlewilde Cemetery.

Another posthumous honor awaited Hachiya in 1980 when the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California, dedicated a new building in its Asian language complex in his honor. Those attending included Monroe Sweetland, Koe Nishimoto, who grew up in Hood River, and Frank’s brother Homer, who was working at the Yokosuka Naval Base in Japan. Nishimoto, a World War II veteran whose family looked after Hachiya’s headstone in Hood River’s Idlewilde Cemetery, commented after the dedication that the honor brought “a great feeling of pride to all Japanese in this valley.”

-

![Frank Hachiya]()

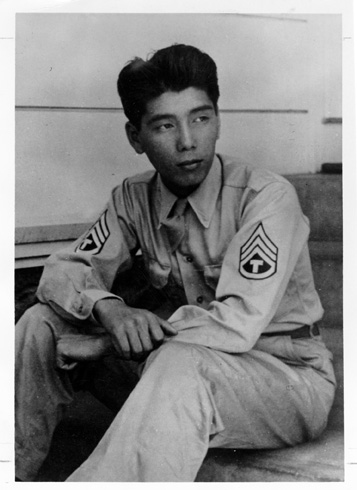

Frank Hachiya.

Frank Hachiya Courtesy Defense Language Institute Foreign Lang. Archives

-

![Camp Savage]()

Camp Savage.

Camp Savage Courtesy Defense Language Institute Foreign Lang. Archives

-

![Memorial Plaque for Hachiya]()

Memorial Plaque for Hachiya.

Memorial Plaque for Hachiya Courtesy Defense Language Institute Foreign Lang. Archives

-

![Building named for Hachiya at Defense Language Institute]()

Building named for Hachiya at Defense Language Institute.

Building named for Hachiya at Defense Language Institute Courtesy Defense Language Institute Foreign Lang. Archives

-

![Monroe Sweetland]()

Monroe Sweetland.

Monroe Sweetland Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

Related Entries

-

![Hood River (city)]()

Hood River (city)

Situated in the Columbia River Gorge about sixty miles east of Portland…

-

![Japanese Americans in Oregon]()

Japanese Americans in Oregon

Immigrants from the West Resting in the shade of the Gresham Pioneer C…

-

![Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon]()

Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon

Masuo Yasui, together with many members of Hood River’s Japanese commun…

-

![Monroe Sweetland (1910-2006)]()

Monroe Sweetland (1910-2006)

Monroe Sweetland's life embraced the cultural revolution of the 1920s, …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Harrington, Joseph D. Yankee Samurai: The Secret Role of Nisei in America's Pacific Victory. Detroit: Pettigrew Enterprises, 1979.

Robbins, William G. "'The kind of person who makes this America strong: Monroe Sweetland and Japanese Americans." Oregon Historical Quarterly 113:2 (Summer 2012): 198-229.

Tamura, Linda. "The Enemy's Our Cousin." Columbia Magazine 20 (Spring 2006).

Tamura, Linda. The Hood River Issei: An Oral History of Japanese Settlers in Oregon's Hood River Valley. Urbana: University of Chicago Press, 1993.