As an Oregon legislator, secretary of state, governor, and United States senator, Mark O. Hatfield played a major role in Oregon and national politics and government during the second half of the twentieth century. He was widely recognized for his principled and often controversial stands on many issues, as well as for his ability to work with his colleagues of both parties.

Born in Dallas, Oregon, in 1922, Hatfield graduated from Willamette University in 1943. After serving in the U.S. Navy during World War II, he completed a master's degree in political science at Stanford University and returned to Willamette as an assistant professor and then dean of students. While still teaching at Willamette, he was elected to the Oregon House of Representatives in 1950 and then to the Oregon Senate in 1954.

With his introduction of a successful measure outlawing racial discrimination in public accommodations in Oregon and his criticism of the anti-communist crusade of Joseph McCarthy, Hatfield established his reputation as a moderate and a maverick Republican. He attracted national attention in 1951 as an early and vocal supporter of the nomination of Dwight Eisenhower for president. He then headed Eisenhower's Oregon campaign organization and was chosen as a delegate to the 1952 Republican National Convention, where he was Oregon's representative on the platform committee. His surprise selection for that post, over the likely candidate, then-Republican Senator Wayne Morse, was an indication of the standing he had achieved very early in his political career.

In 1956, Hatfield was elected secretary of state. Two years later, he ran for governor, with a strong grassroots organization. In the course of the campaign, he distanced himself from Republican Party positions on such issues as capital punishment and labor unions, and the national party refused to support him in the primary election. Nevertheless, his strategy turned out to be a significant factor in his victory over incumbent Democratic Governor Robert Holmes. It was a notable success in an election year that was a disaster for the Republican Party across the country.

Throughout his career, Hatfield pursued a balance between liberal and conservative political philosophies, while maintaining his evangelical religious beliefs. As governor, he supported aspects of the environmental movement while remaining attentive to the needs of agriculture and the timber industry. Both fit into his concept of protecting and developing Oregon's "livability." He opposed cuts in services to the poor and the elderly but spoke out for individual responsibility and against undue interference by the national government in state and local matters.

In 1962, Hatfield won a second term as governor, again running a decidedly independent campaign. He avoided appearances with other Republican candidates and kept the Republican label off his campaign signs. Rumors began to circulate that he would be the party's candidate for the vice presidency in 1964. Despite the party's ongoing uneasiness about his political stands, Hatfield's appeal was such that he was invited to deliver the keynote speech at the 1964 national convention. The convention gave the presidential nomination to the conservative Barry Goldwater, so it is not surprising that Hatfield's moderate speech occasioned bitter criticism from officeholders and rank-and-file Republicans, although others expressed strong support for his stands.

During the annual conference of governors in 1965, Hatfield, along with George Romney of Michigan, voted against a motion in support of the war in Vietnam. Romney later changed his mind, but Hatfield's opposition to the war became the centerpiece of his public life. When another motion of support was presented at the 1966 governors' conference, Hatfield cast the lone negative vote. He was convinced that North Vietnam's motive was Vietnamese nationalism rather than communism and believed that nationalism was a force that could not be denied.

In 1966, to the surprise of very few observers, Hatfield announced his candidacy for a seat in the U.S. Senate. Although his opposition to the war became an issue in the campaign, he won a close race against his pro-war Democratic rival, Congressman Robert Duncan. Oregonians chose Tom McCall to be Hatfield's successor in the governor's office. Despite their agreement on many issues, the two were never close, and McCall made many insiders aware of his intention to challenge Hatfield in the 1972 senatorial race.

Senator Hatfield quickly made his mark in his new arena, while avoiding easy classification as a liberal or a conservative. He was often at odds with the White House, whether the president was a Democrat or a Republican. Although he consistently emphasized his support for the troops, his opposition to the Vietnam war did not endear him to President Lyndon Johnson. He openly criticized President Richard Nixon's "Southern strategy," which was intended to strengthen the Republican Party by recruiting conservative Southern Democrats. Hatfield objected to the plan as essentially racist and earned himself a place on Nixon's "enemies list."

Hatfield's Senate agenda reflected his strong convictions and the diverse interests of his constituency. Generally in favor of environmental protection, he nevertheless supported logging on public lands. When oil supplies were interrupted by the Arab-Israeli war in 1973, Hatfield developed a plan to deal with the energy crisis and its long-term implications. While the entire plan did not become law, its proposals foreshadowed later measures. He promoted civil rights and a nuclear freeze and opposed abortion and the death penalty. In 1991, his was one of only two Republican senate votes against President George H.W. Bush's resolution for the Gulf War; he and Senator Charles E. Grassley (R-Iowa) joined 45 Democrats in unsuccessful opposition.

Even though he represented a state with a relatively small population, Hatfield rose to a position of prominence in the Senate. His standing and effectiveness brought many benefits to his home state. With Republican control of the Senate, Hatfield's seniority made him chair of the powerful Appropriations Committee from 1981 until 1987 and again from 1995 until 1997. He retired from the Senate in 1997.

Back in Oregon, Hatfield taught at George Fox University and at the Hatfield School of Government at Portland State University. He died on August 7, 2011, at age 89. His service to the state and the nation has been recognized by placing his name on the Oregon State University Hatfield Marine Science Center and the Hatfield Research Centers at the National Institutes of Health and at Oregon Health and Sciences University, among many other honors.

-

![Governor Mark Hatfield , Georgia Pacific mill, Toledo, Oct. 1958.]()

Hatfield, Mark, at GP Toledo, Oct 1958.

Governor Mark Hatfield , Georgia Pacific mill, Toledo, Oct. 1958. Oreg. State Univ. Archives, A 98.33.511c N 2678

-

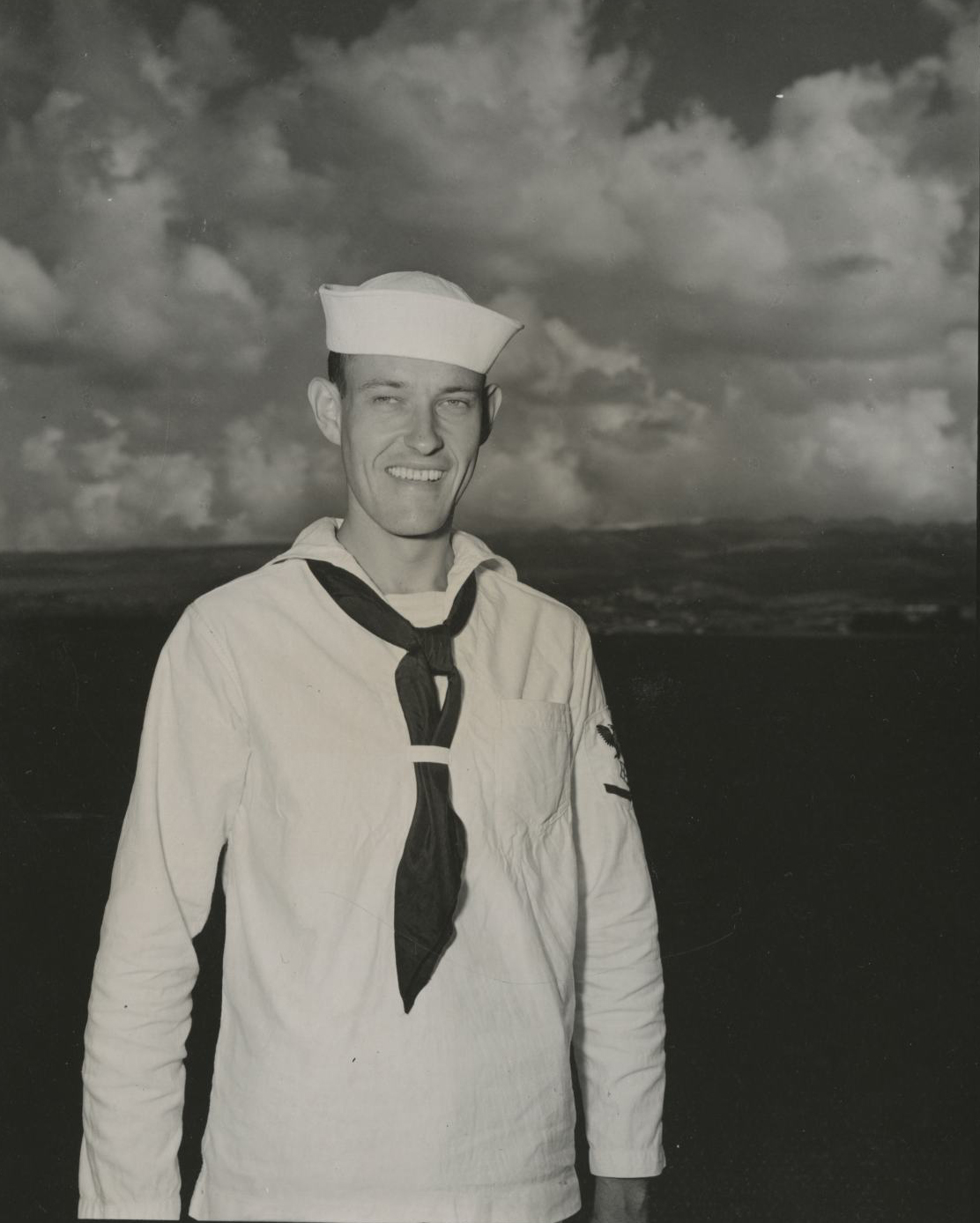

![Mark Hatfield.]()

Hatfield, Mark.

Mark Hatfield.

-

![Govenor Mark O. Hatfield signs legislation changing the name of Oregon State College to Oregon State University, March 1961.]()

Hatfield, Mark, OSU name change, 1961.

Govenor Mark O. Hatfield signs legislation changing the name of Oregon State College to Oregon State University, March 1961. Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Harriet's Coll., HC2227

-

![Mark Hatfield (l), Robert W. MacVicar, and John Byrne at Hatfield Marine Science Center dedication, Newport, 1983.]()

Hatfield, Mark, at MSC dedication, 1983.

Mark Hatfield (l), Robert W. MacVicar, and John Byrne at Hatfield Marine Science Center dedication, Newport, 1983. Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Harriet's Coll., P185:2

Related Entries

-

![Antoinette Marie Kuzmanich Hatfield (1929–)]()

Antoinette Marie Kuzmanich Hatfield (1929–)

Antoinette Hatfield’s talents and sense of style and her support of the…

-

![Hatfield Marine Science Center and Visitor Center]()

Hatfield Marine Science Center and Visitor Center

The Hatfield Marine Science Center (HMSC) on Yaquina Bay in Newport was…

-

![Thomas William Lawson McCall (1913-1983)]()

Thomas William Lawson McCall (1913-1983)

Tom McCall, more than any leader of his era, shaped the identity of mod…

-

![Willamette University]()

Willamette University

Willamette University, the oldest university in the West, was founded i…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Cross, Travis. "The 1958 Hatfield Campaign in Oregon." Western Political Quarterly (June 1959).

Eells, Robert, and Bartell Nyberg. Lonely Walk: The Life of Senator Mark Hatfield. Portland: Multnomah Press, 1979.

Hatfield, Mark O. Against the Grain: Reflections of a Rebel Republican. Ashland, Ore.: White Cloud Press, 2001.