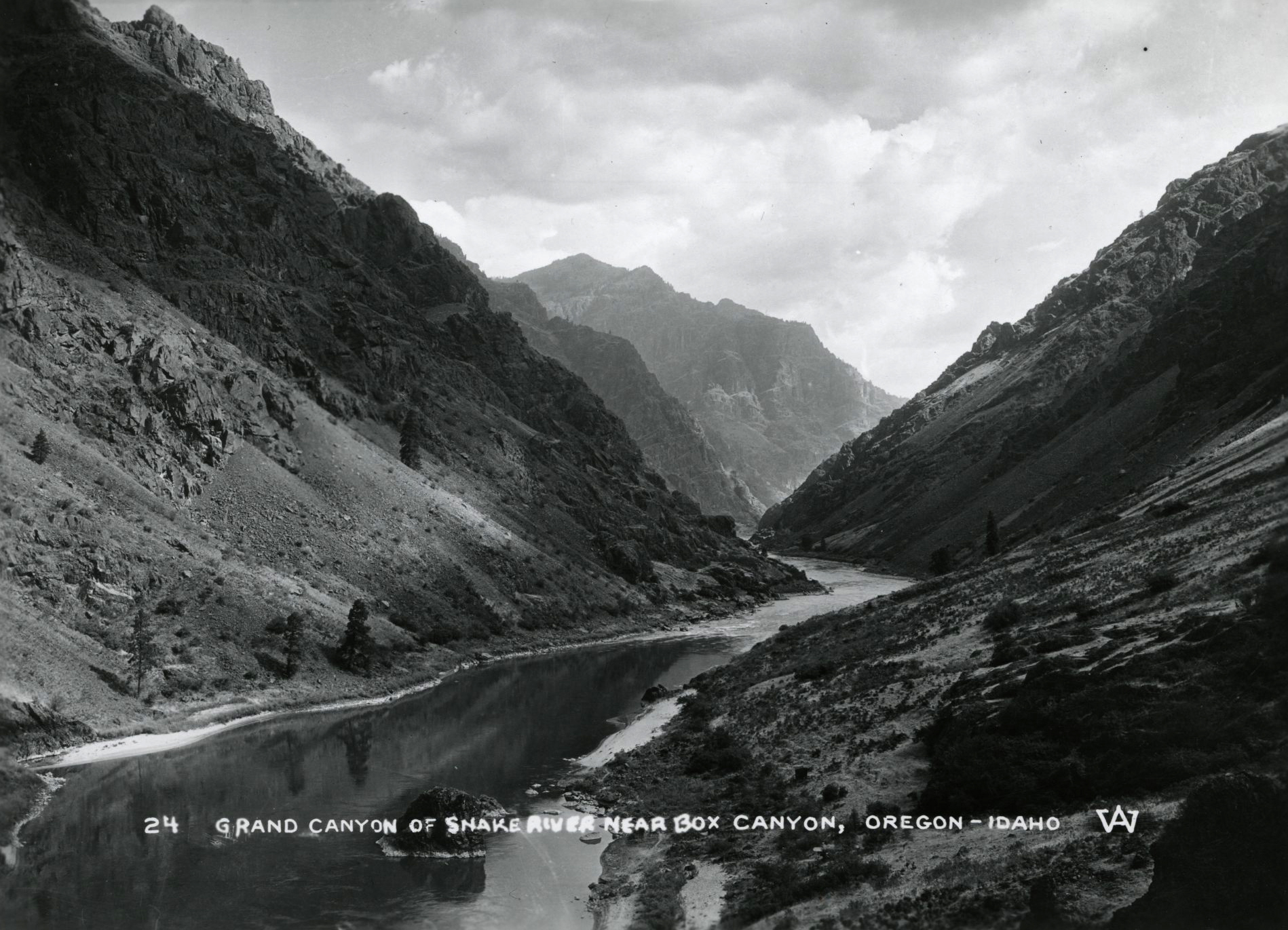

As the country’s deepest canyon, at 7,993 feet, Hells Canyon is a place of superlatives rooted in its remoteness. It is a place where people can hike, raft, and hunt and experience an exceptional landscape with unique geographic features and a sense of isolation. Carved by the Snake River, Hells Canyon follows Oregon’s northeastern border with Idaho for more than one hundred miles, from Oxbow Dam northwest to the mouth of the Grand Ronde River. Relatively few people have called Hells Canyon home, but its history illustrates several key themes in Oregon history, from economic and social exploitation to wilderness preservation.

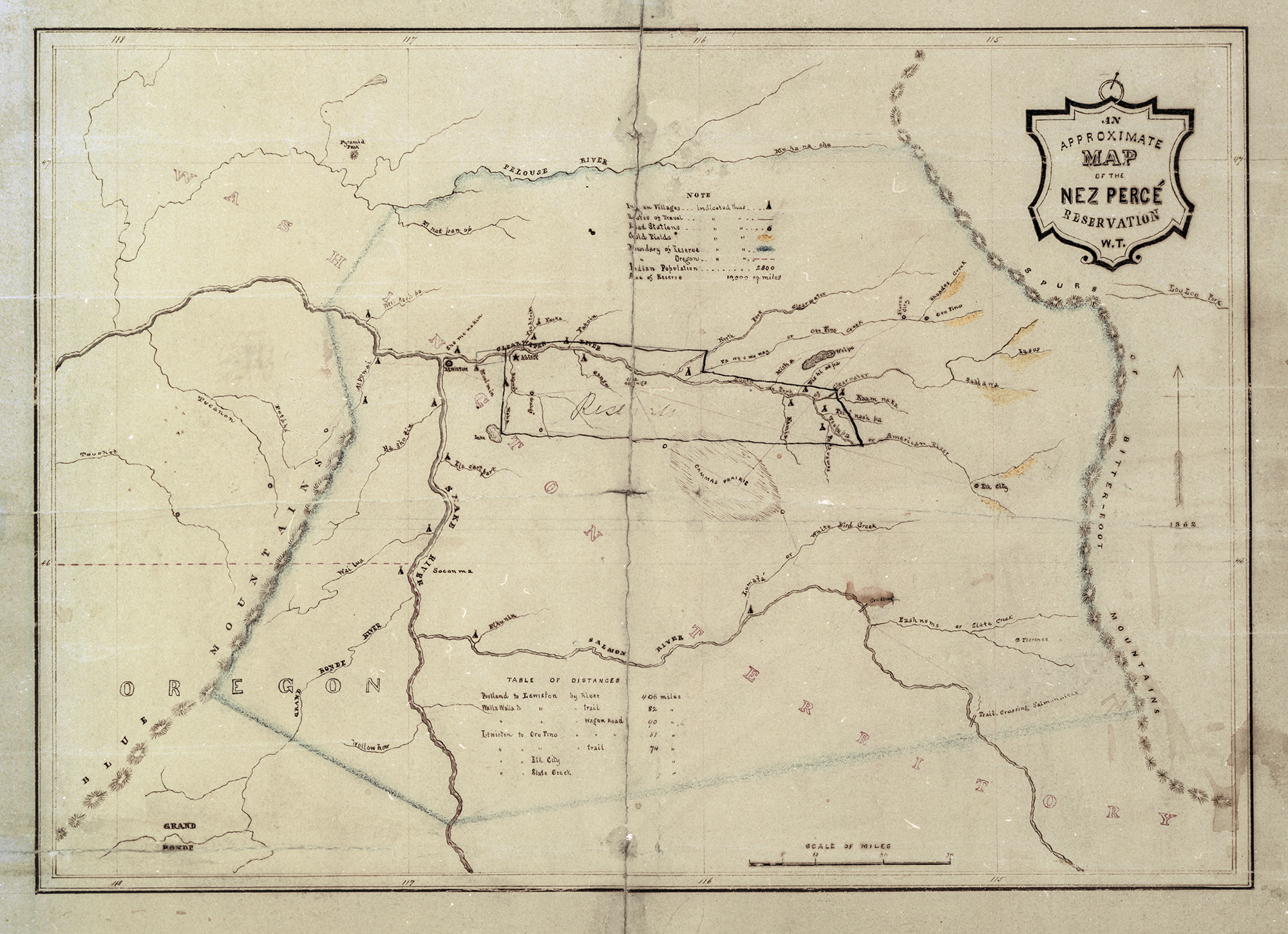

Hells Canyon is on traditional Nez Perce (Nimiipuu) territory. For thousands of years, the abundant salmon runs, warmer winter climates, and bighorn sheep and other wildlife have made it attractive to the area’s Indigenous people. When agents of empire first moved into the Oregon Country, Hells Canyon received scant attention given that its deep chasm significantly slowed travel. When Sgt. John Ordway of the Lewis and Clark Expedition visited the canyon in June 1806, he reported great rapids and a riverbank that was “in most places solid and perpendicular rocks, which rise to a great hight [sic].”

The Pacific Fur Company sent men through the region in 1811, with Wilson Price Hunt leading them into the canyon before having to turn back. Capt. Benjamin Bonneville, a U.S. Army officer on leave, attempted to navigate Hells Canyon in 1834 and memorably captured the challenge of the place. “The grandeur and originality of the views presented on every side beggar both the pencil and the pen,” he wrote. “Nothing we had ever gazed upon in any region could for a moment compare in wild majesty and impressive sternness, with a series of scenes which here at every turn astonished our sense and filled us with awe.” That sense of impenetrability and indescribable power continues to be ascribed to Hells Canyon.

Following the failures of non-Indigenous travelers to locate a manageable route through Hells Canyon, fur traders managed to navigate the canyon to extract marketable pelts. Overland migrants on the Oregon Trail largely avoided the canyon, and miners ended up being the vanguard to penetrate the area. A trespasser found gold on Nez Perce land in 1860 and initiated a flood of additional trespassing miners, which in 1863 led to a treaty between the United States and Nez Perce that vastly shrunk their traditional territory. To help supply the growing white population, miners near Hells Canyon encouraged promoters to use steamboats to navigate the chasm; but the boats crashed on the rocks, keeping Hells Canyon from becoming an easy stop in what became a growing regional transportation network.

Beginning in the mid-1860s, Chinese miners worked the rocky shorelines and deep side canyons in Hells Canyon to find gold and other valuable minerals. In 1887, two Chinese crews were working claims near Deep Creek when they were murdered by white men from Wallowa County. The details of the massacre remain somewhat uncertain, but as many as thirty-four men were killed and mutilated, presumably to obtain their gold. Racism and greed explain both the crime and the anemic investigation that followed but offered no closure or justice.

Hells Canyon largely thwarted the efforts of developers to take advantage of technological innovations. The canyon was too deep, the rock walls too steep, and the gap between opposing rims was too narrow for railroads to traverse the canyon. There were few roads, no bridges, and only a handful of people. But Hells Canyon was an attractive, even an ideal, location for hydroelectric dams.

The federal government proposed the Hells Canyon High Dam in the 1940s as a way to extend the New Deal-sponsored hydroelectric development of the Columbia River Basin, which includes the Snake River as a tributary. The high dam would have ended all salmon runs upstream, but more than concern over fish shaped the opposition. The Idaho Power Company argued for private rather than public power. The private side won the debate, and Idaho Power built three low dams: Brownlee (1958), Oxbow (1961), and Hells Canyon (1967). The shift to private power was part of a backlash against the federal government’s authority over hydropower resources in the Pacific Northwest, which had grown considerably since the 1930s.

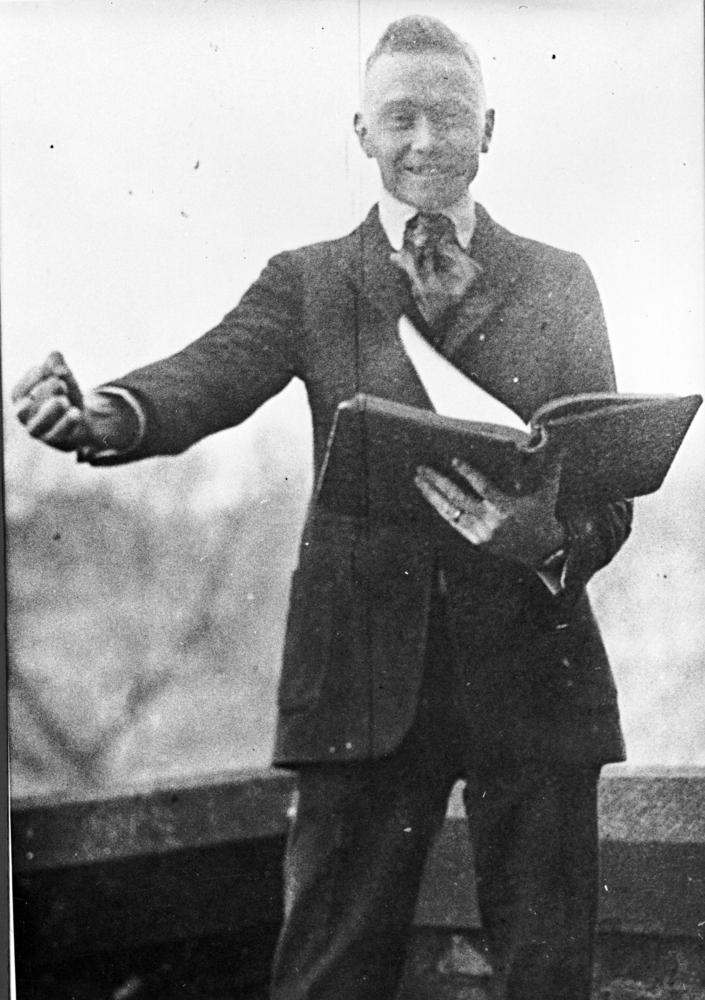

During the 1960s, a new debate emerged over a potential fourth dam in Hells Canyon, High Mountain Sheep Dam. Again, federal officials debated with private power officials over whose dam to build, but this time the question landed before the U.S. Supreme Court. Justice William O. Douglas wrote the majority opinion in Udall v. Federal Power Commission (1967). Douglas had owned a cabin near Lostine, a small town near Enterprise in the nearby Wallowa Mountains, and he knew the Hells Canyon country well. He wondered whether any dam should be constructed, citing concerns about fish, suggesting the possibility of alternative energy sources, and questioning whether there was a “need to destroy the river.” The public interest, he concluded, was more important than any kilowatts that might be extracted from the Snake’s flowing water.

The Supreme Court decision marked a change in the perception of Hells Canyon, as its preservation became more important than its development. In 1967, the Hells Canyon Preservation Council was created to lobby for the protection of the deepest gorge in North America. Robert Packwood, who was elected to the U.S. Senate from Oregon in 1968, became an enthusiastic sponsor of legislation to make Hells Canyon a national recreation area. The legislation took time and required negotiation, but in 1975 Congress passed and President Gerald Ford signed the law, setting aside some 662,000 acres of Hells Canyon as a national recreation area. The legislation also protected the 192,000-acre Hells Canyon Wilderness and included 62 miles of the Snake River in the Wild and Scenic River system.

-

![]()

Snake River canyon in northeastern Oregon.

OSU Special Collections & Archives Research Center, Oregon State University. "Snake River canyon in northeastern Oregon" Oregon Digital. -

![]()

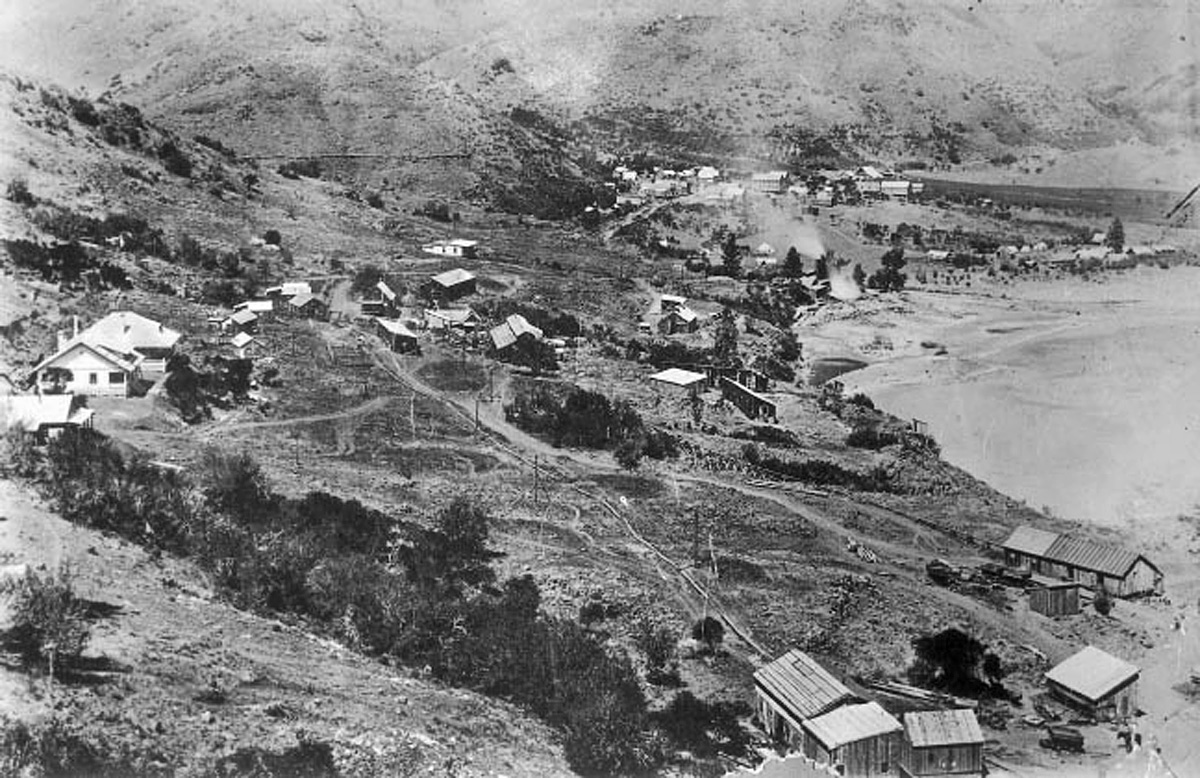

Eureka Bar near mouth of Imnaha River, Hells Canyon.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 004079

-

![]()

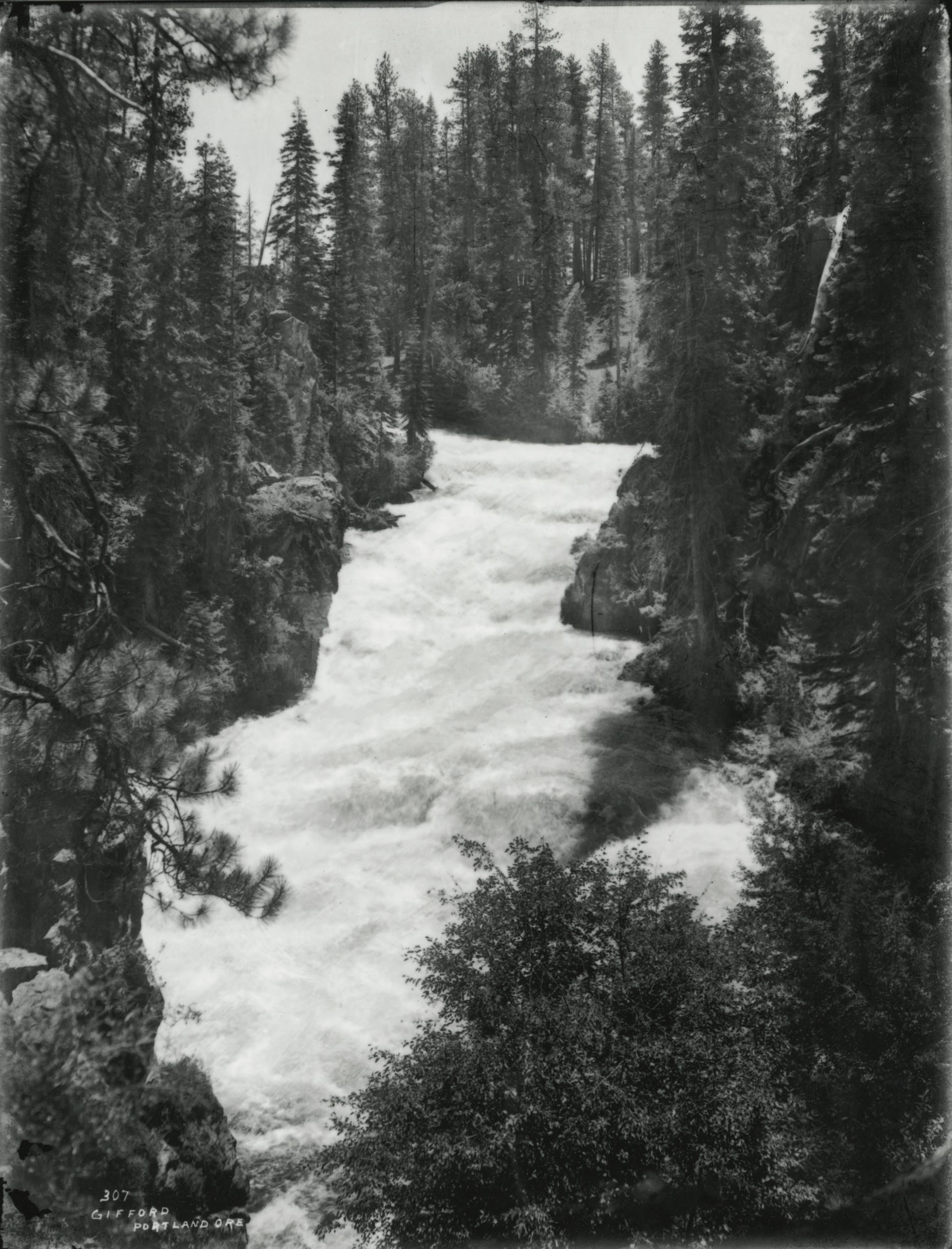

Hells Canyon.

Courtesy U.S. Forest Service -

![]()

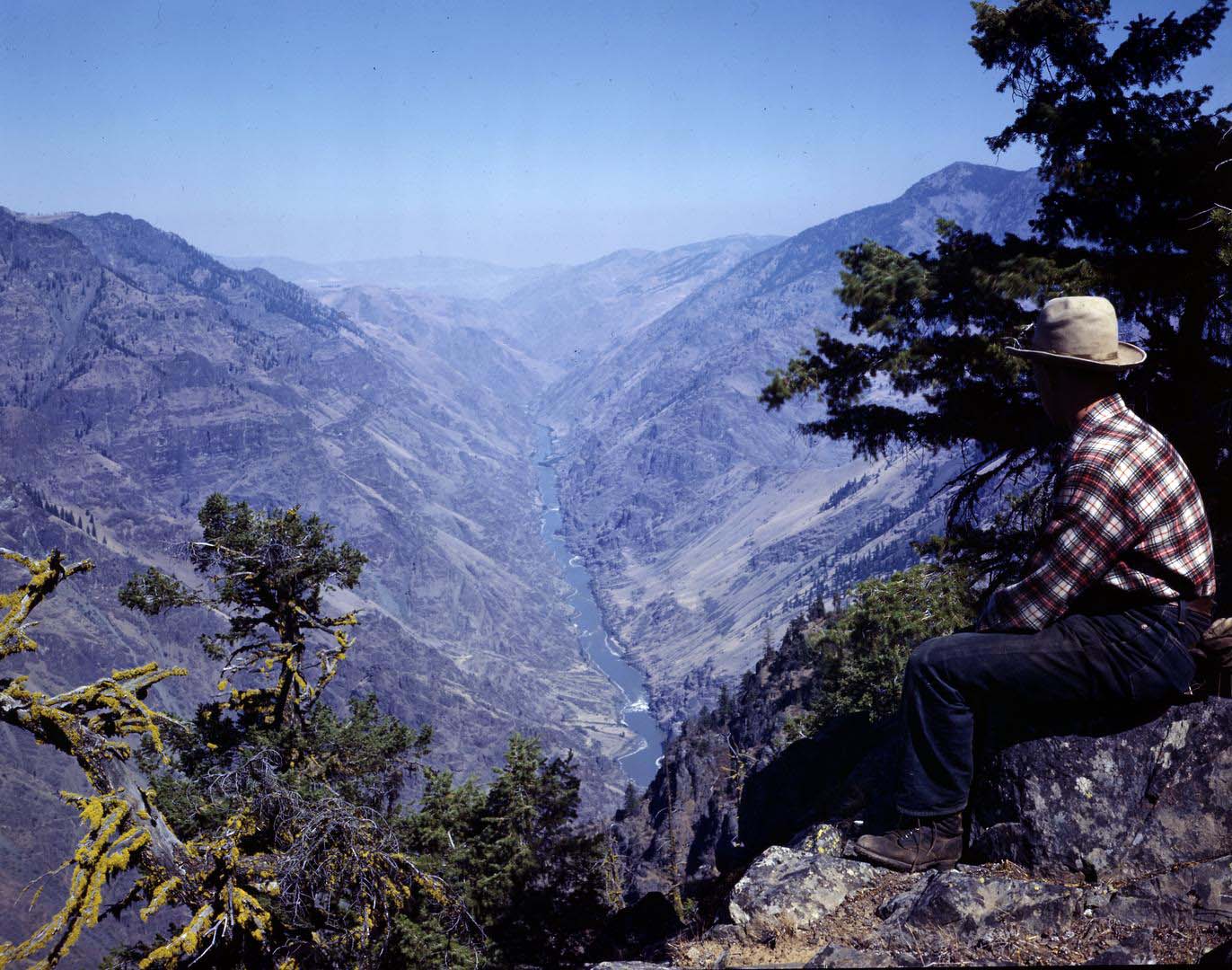

Hells Canyon near Baker, Oregon, 1950.

Gerald W. Williams Collection, Oregon State University. "Hells Canyon near Baker, Oregon" Oregon Digital -

![]()

Hells Canyon, Buckhorn Overlook, 2019.

Courtesy Gary Halvorson, Oregon State Archives -

![]()

View of Hells Canyon, 2015.

Courtesy A.E. Platt

-

![]()

Hells Canyon Dam on the Snake River, 1967.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi93275

-

![]()

Hells Canyon Dam Hearing, Portland State, 1955.

Oregon Historical Soc. Research Library, OrgLot1284_2445_7

Related Entries

-

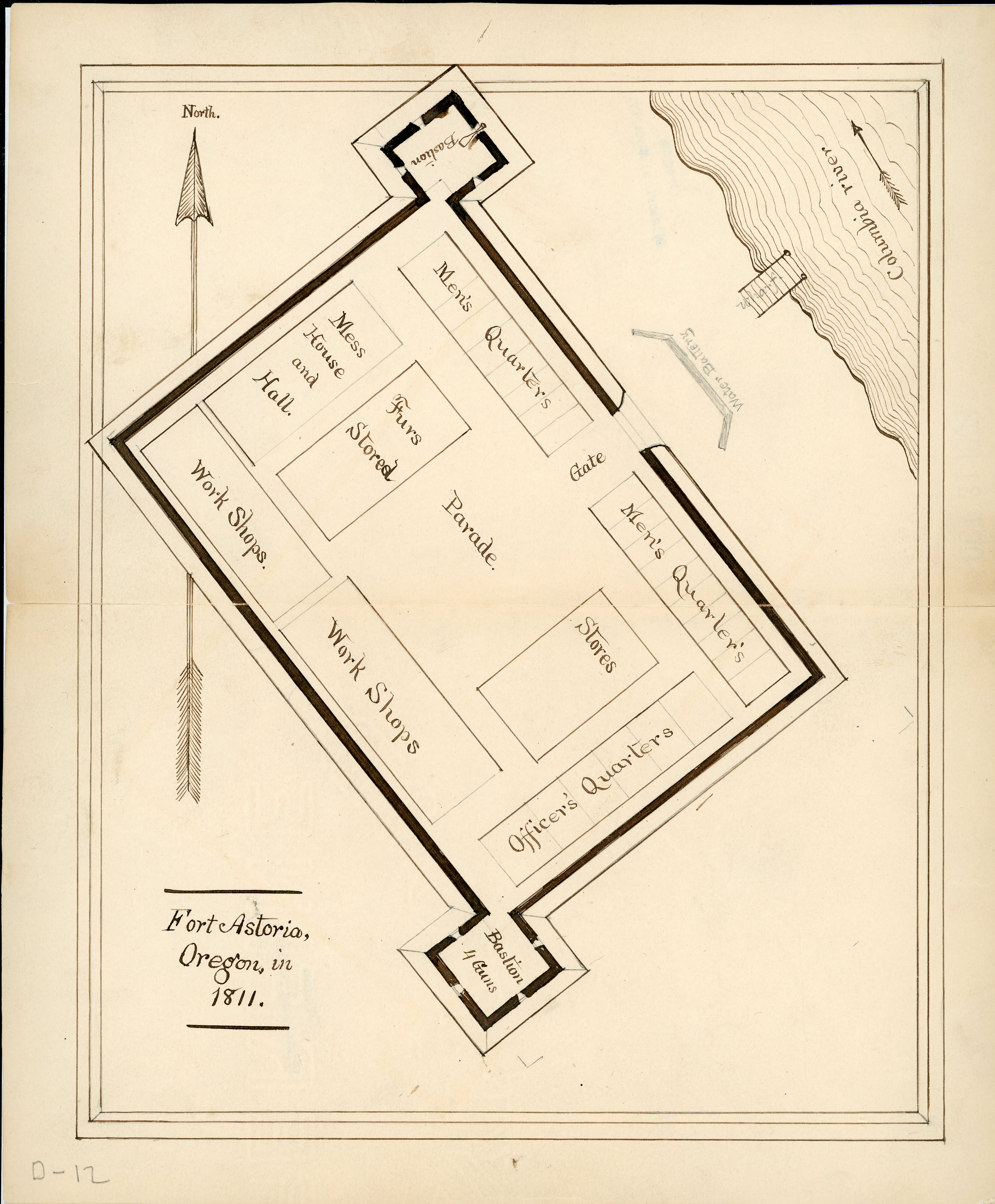

![Astor Expedition (1810-1813)]()

Astor Expedition (1810-1813)

The Astor Expedition was a grand, two-pronged mission, involving scores…

-

![Chinese Massacre at Deep Creek]()

Chinese Massacre at Deep Creek

Of the many crimes and injustices committed against early Chinese immig…

-

![Chinese mining in Oregon]()

Chinese mining in Oregon

The city of Guangzhou (formerly known to Westerners as Canton) is the c…

-

![Copperfield]()

Copperfield

The unincorporated community of Copperfield, also known as Oxbow, is lo…

-

![National Wild and Scenic Rivers in Oregon]()

National Wild and Scenic Rivers in Oregon

The world's first and most extensive system of protected rivers began w…

-

![Native American Treaties, Northeastern Oregon]()

Native American Treaties, Northeastern Oregon

After American immigrants arrived in the Oregon Territory in the 1840s,…

-

![Oregon Trail]()

Oregon Trail

Introduction In popular culture, the Oregon Trail is perhaps the most …

-

![Snake River]()

Snake River

The Snake River has its headwaters at an elevation of 8,200 feet on the…

-

![William O. Douglas (1898-1980)]()

William O. Douglas (1898-1980)

Although he hailed from the State of Washington, William O. Douglas rep…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Ashworth, William. Hells Canyon: The Deepest Gorge on Earth. New York: Hawthorn Books, 1977.

Brooks, Karl Boyd. Public Power, Private Dams: The Hells Canyon High Dam Controversy. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006.

Dant Ewert, Sara E. “Evolution of an Environmentalist: Senator Frank Church and the Hells Canyon Controversy.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 51.1 (Spring 2001): 36-51.

Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. University of Nebraska Press.

Neuberger, Richard L. “Hells Canyon, The Biggest of All.” In They Never Go Back to Pocatello: The Selected Essays of Richard Neuberger, edited by Steve Neal, 14-29. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1988.

Nokes, R. Gregory. Massacred for Gold: The Chinese in Hells Canyon. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2009.

Sowards, Adam M. The Environmental Justice: William O. Douglas and American Conservation. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2009.