White supremacy dominated opposition to slavery in mid-nineteenth-century Oregon and shaped the conservatism of its Civil War-era Republican Party. But when the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act re-opened controversies over slavery with unprecedented fervor, antislavery radicals took the lead in organizing an insurgent Republican Party. Henry Hicklin was one such radical in the Oregon Territory during the 1850s. Hicklin never acted alone but was part of a small group of religious men who sought the immediate abolition of slavery. To that end, they played an important role in the early formation of Oregon’s Republican Party.

Henry Hamilton Hicklin was born in 1825 near San Jacinto, a small town in Jennings County, Indiana, just north of the Ohio River and the border of the Upper South. He grew up in a community of Christian abolitionists that included three of his uncles—James, Thomas, and Lewis Hicklin—who were leaders of the group. They organized antislavery societies, collaborated with Black abolitionists to assist fugitives from slavery, faced down anti-abolitionist mobs, and led petitions to abolish slavery and attack Indiana’s Black Laws. James Hicklin ran for the state legislature on the 1844 Liberty Party ticket, which championed immediate emancipation and racial egalitarianism. After local Baptist leaders expelled him for “aiding to convey slaves from their Masters,” the Hicklin family joined the Neil’s Creek Baptist Antislavery Church, which later helped found the biracial Eleutherian College in Lancaster, Indiana.

Henry Hicklin traveled overland in 1851 with his immediate family and their relations in the Denny, Stott, and Baxter families. They settled on Tualatin Kalapuya traditional land along the Lower Tualatin River in present-day Washington County, where they joined the families of Augustus Fanno, Wilson Tigard, George Cooke (the brother of physician and suffragist Mary Anna Cooke Thompson), and others who had antislavery backgrounds. Together they would boycott the dominant Democratic and anti-immigrant American parties and oppose calls for a constitutional convention. The 1857 constitutional referendum would reveal their dissenting views most starkly when the male heads of the allied families cast dissenting votes against the constitution, slavery, and the exclusion of "Free negros.”

In 1854, a new party was formed in the upper Midwest—the Republican Party—led by anti-slavery radicals who insisted on uncompromising opposition to the extension of slavery and an end to what they saw as slaveholders’ control of the federal government. The radicals remained fixed on the immorality of human bondage, a strategy of containment, and the eventual destruction of chattel slavery in the United States.

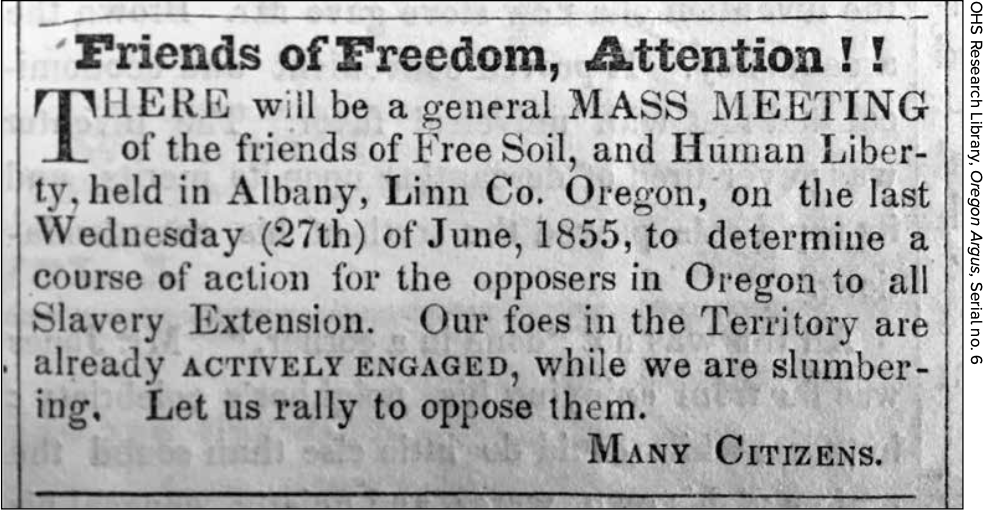

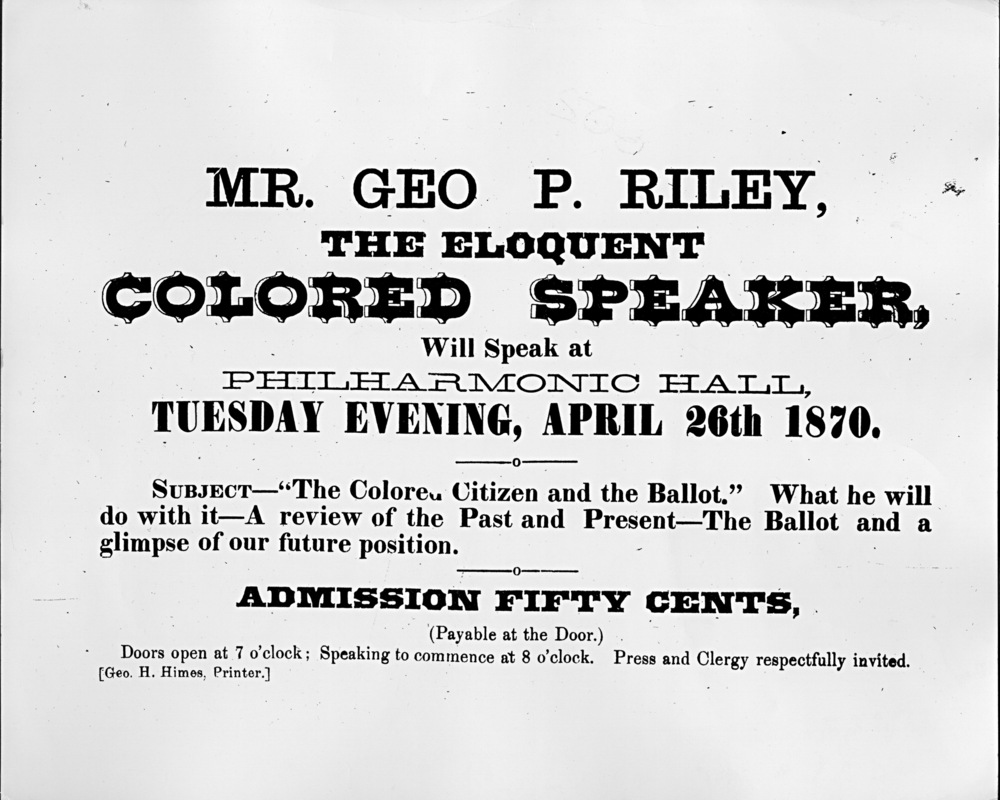

Those goals surely inspired Hicklin and his two younger brothers to join the Oregon Free Soil Convention that convened in Albany in June 1855. Recognized as the first antislavery political gathering in Oregon Territory, the convention passed resolutions condemning all federal legislation on slavery since 1850, including the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, as "unjust and anti-republican, oppressive and cruel.” Attendees insisted on “the overthrow of an institution so utterly opposed in every principle of political, as well as of moral and religious right.” In a final resolve, they celebrated the women present for their shared commitment to “human liberty." A few weeks later, Black abolitionist Abner H. Francis, who lived in Portland, wrote his friend Frederick Douglass that while “it will be a hard contest” the “friends of freedom” were mobilizing in Oregon.

In 1855–1856, Hicklin helped organize the “strongly antislavery” Sylvania Baptist Church in Washington County, where he eventually preached. In October 1856, he served as secretary at the founding of the Washington County Republican Party and as liaison to the Clackamas County party. Like his abolitionist uncles in Indiana, he made the unusual decision to remain unmarried and to devote himself to antislavery politics and religion while in Oregon.

In February 1857, along with many men from the Free Soil Convention, Hicklin joined the Territorial Free State Republican Convention in Albany. He and abolitionist minister Thomas S. Kendall were on the platform committee with moderates and conservatives who typified those who would come to dominate the party. The convention refused race-based appeals, championed "the principles of the Declaration of Independence," and condemned slavery as "evil in its effects and consequences.” Hicklin served as a precinct clerk for the first constitutional referendum on November 9, 1857.

Even before Congress admitted Oregon as a “free” state in 1859, a conservative leadership began displacing radicals in Oregon’s Republican Party, vocally rejecting abolitionism, and appealing to “free white men.” Hicklin did not attend the 1858 territorial or Washington County Republican conventions, the latter of which disclaimed “all association or sympathy with the abolition party of the Garrison School.”

In early 1860, Hicklin returned to Indiana, where he lived in the household of Eleutherian College founder Reverend Thomas Craven. In September 1861, he was an early volunteer for the 36th Regiment of the Indiana Infantry and went on to fight in some of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War, including the Battle of Chickamauga where he was briefly captured. He returned to Indiana in 1864 and four years later moved to Greenwood County, Kansas, where he established a farm, married, and had two sons. He remained active in Republican politics until his death in 1873.

The hostility to abolitionists that characterized Oregon’s antebellum political environment obscures the contributions Hicklin and his fellow radicals made in the formation of Oregon’s Republican Party. More than most Oregonians, he and others contributed to an interracial movement for emancipation, mass antislavery politics, and a war of abolition that radically reshaped the nation.

-

![]()

Oregon Argus, June 1855. Friends of Freedom announcement.

Courtesy Oregon Historical Quarterly

-

![]()

"Free Soil Convention," Oregon Argus, July 7, 1855.

Oregon Argus

-

![]()

"Free Soil Convention," Oregon Argus, July 7, 1855.

Oregon Argus

-

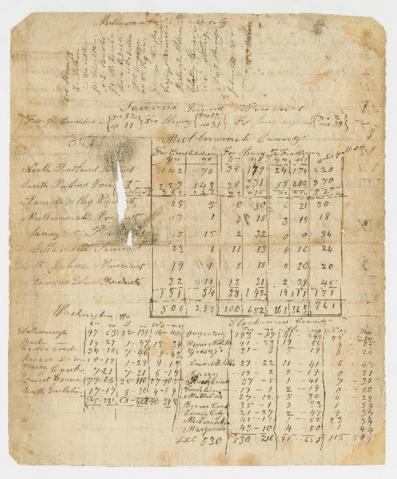

![Hicklin's name is mid-page.]()

Civil War Draft Records, Indiana, 1863.

Hicklin's name is mid-page. U.S. National Archives

-

![]()

Battle of Chickamauga, Sept. 19 & 20, 1863. Lithograph created c.1890.

Courtesy Kurz & Allison, Library of Congress

-

![Hicklin's signature on a petition for a prohibitory liquor law.]()

H.H. Hicklin signature, c.1850.

Hicklin's signature on a petition for a prohibitory liquor law. Courtesy Oregon State Archives. Papers of the Provisional & Territorial Governments, 9099.

Related Entries

-

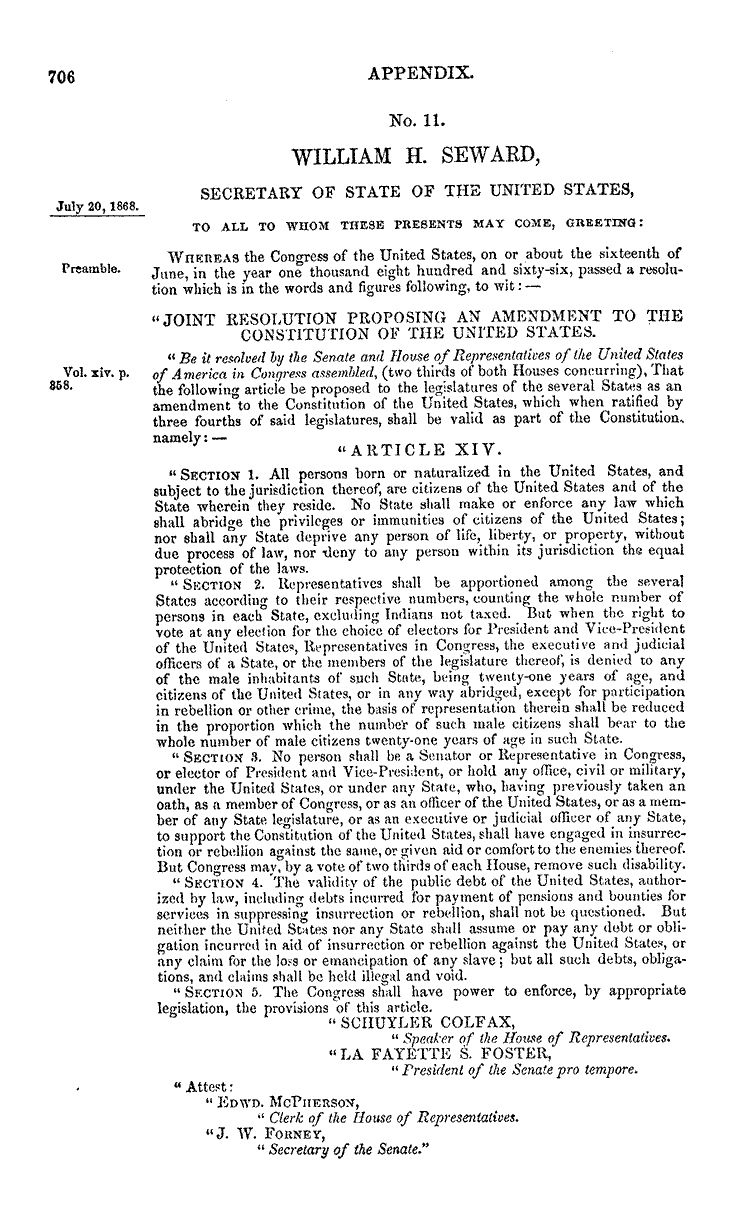

![14th Amendment]()

14th Amendment

The Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution declared that the fed…

-

![15th Amendment]()

15th Amendment

Civil War Reconstruction arguably culminated with the Fifteenth Amendme…

-

![Abner Hunt "A. H." Francis (c. 1812–1872) and Isaac "I. B." Francis (1798-1856)]()

Abner Hunt "A. H." Francis (c. 1812–1872) and Isaac "I. B." Francis (1798-1856)

A. H. Francis, a free Black, was a merchant and activist who in 1851 op…

-

![Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon]()

Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon

Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws th…

-

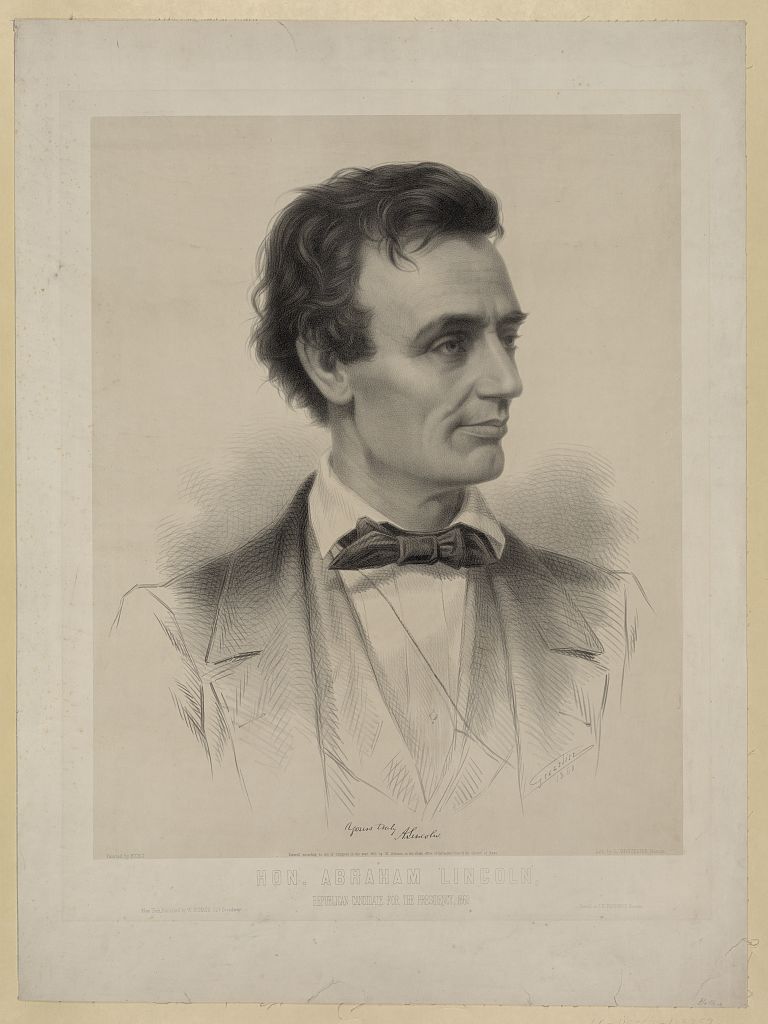

![Election of 1860]()

Election of 1860

The presidential election of 1860 was a turning point in Oregon politic…

-

![Holmes v. Ford]()

Holmes v. Ford

On April 16, 1852, a former slave named Robin Holmes filed suit against…

-

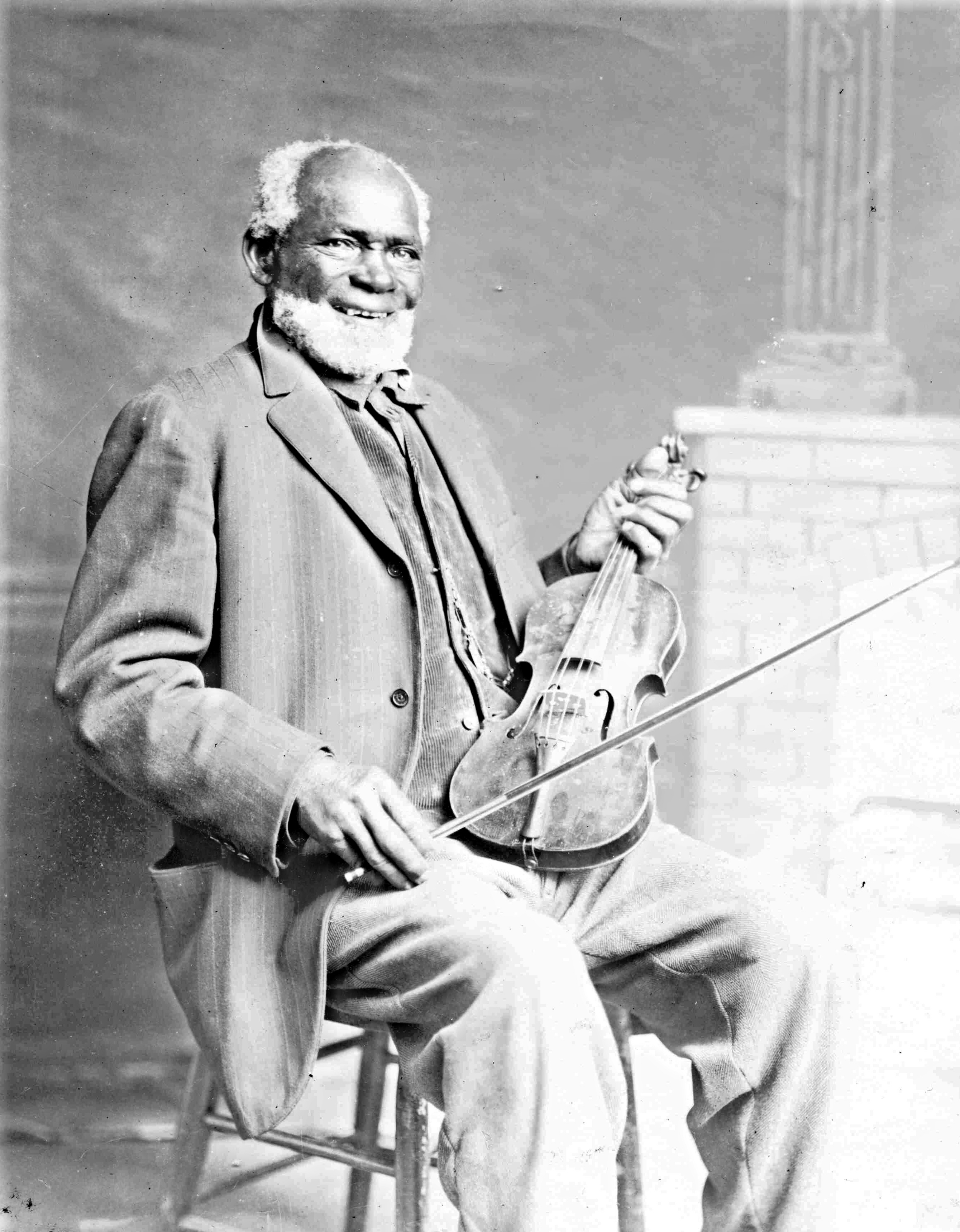

![Louis Southworth (1829–1917)]()

Louis Southworth (1829–1917)

Louis Southworth came to Oregon in 1853, a time that was less than hosp…

-

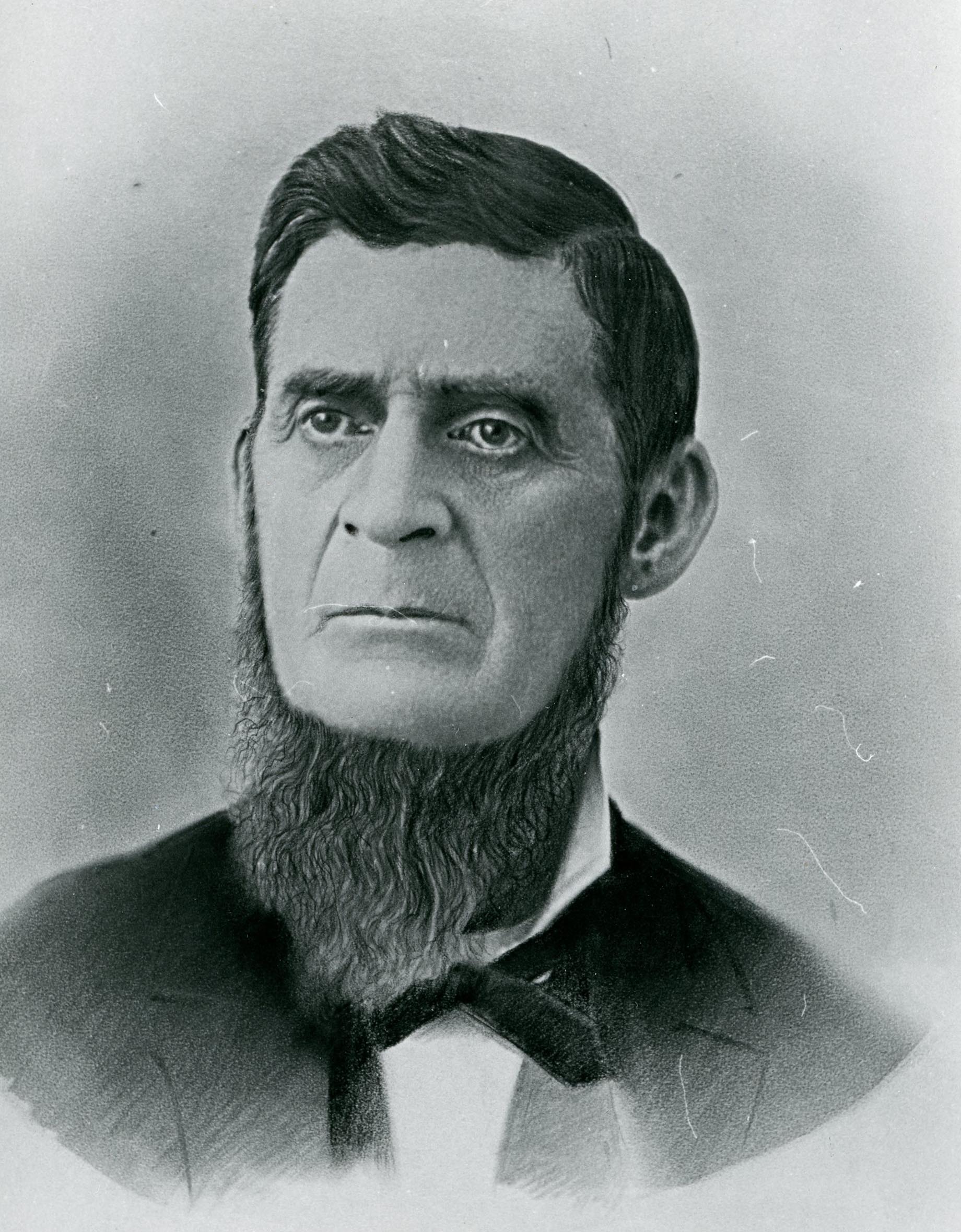

![Obed Dickinson (1818–1892)]()

Obed Dickinson (1818–1892)

When Obed Dickinson arrived in Salem in 1853 to become pastor of the Co…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Bourke, Paul, and Donald DeBats. County: Politics and Community in Antebellum America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995.

Davenport, T. W. "Slavery Question in Oregon.” Part I. Oregon Historical Quarterly 9:3 (September 1908): 236-37; Part II, 9:4 (December 1908): 309-73.

Eureka Herald and Greenwood County Republican (Kansas), January 26, 1871; April 13, 1871.

Evansville Daily Journal (Indiana), June 3, 1865.

Foner, Eric Foner. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War. Rev. ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Furnish, Mark Allan. A Rosetta Stone on Slavery's Doorstep: Eleutherian College and the Lost Antislavery History of Jefferson County, Indiana. PhD diss., Purdue University, May 2017.

Johannsen, Robert W. Frontier Politics and the Sectional Conflict: The Pacific Northwest on the Eve of the Civil War. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1955.

_____. “Specters of Disunion: The Pacific Northwest and the Civil War.” Pacific Northwest Quarterly (July 1953), 106-114.

Karp, Matthew. “The Mass Politics of Antislavery.” Catalyst 3:2 (Summer 2019), 131-78.

Labbe, Jim M. “The Colored Brother’s Few Defenders: Oregon Abolitionists and their Followers.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 120:4 (Winter 2019): 440-65.

“Letter from the Oregon Territory.” Frederick Douglass' Paper, August 24, 1855.

Matton, C.H. Baptist Annuls of Oregon. Vol. 1. McMinnville, OR: Telephone Register Publishing, 1905.

Sinha, Manisha. The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition. New Haven, CN: Yale University Press, 2016.

Weekly Oregonian, July 7, 1855; November 29, 1856; February 21, 1857.

Woodward, Walter Carlton. “The Rise and Early History of Political Parties in Oregon.” Part IV. Oregon Historical Quarterly 12:3 (September 2011): 251-58.