The Hillcrest Youth Correctional Facility in Salem was a prison for Oregon youth for over a hundred years. The publicly owned institution opened as the Oregon State Industrial School for Girls in 1914. Male prisoners were housed there beginning in the 1970s. Hillcrest’s development and the changes it made over time reflect evolving theory and practice in the institutionalization of Oregon’s juveniles, including changes in programming and housing. The facility closed in 2017.

The Oregon State Industrial School for Girls was situated on 671 acres of land about three miles southeast of downtown Salem and adjacent to the State Institution for the Feeble-Minded (later renamed the Fairview Training Center), established in 1908. It was the era of the Cottage System of reform ideals, which advocated that “wayward” girls who the courts had determined should be institutionalized could be rehabilitated if they were housed in a family setting and exposed to farmwork and education in the household arts.

The school had a large brick cottage, where females from thirteen to twenty-three years old were housed in individual rooms. The farm had facilities for chickens, hogs, cows, and horses. By the 1920s, the school was working with Oregon State University for advice on crops and livestock to achieve its goal of becoming self-supporting.

Though it was called a school, the Oregon State Industrial School for Girls followed practices common to the treatment of girls at reform institutions throughout the United States. The first residents were sent to the Industrial School for offenses labeled “incorrigible,” “immorality,” “vagrancy,” “delinquent, immoral,” “larceny,” and “evil associates.” Their education focused on household labor and morality. “It is not the idea to lock these young girls up so they cannot do the wrong things they seem to have the tendency to do,” principal teacher Clara A. Ahlgren told the Daily Oregon Statesman in 1914, “but to give them a truer, clearer conception of what is good and makes for happiness.”

Under the supervision of Oregon’s Board of Eugenics, which operated from 1917 to 1981, the treatment of some residents included forced sterilization. Sterilization was a “great benefit in handling this class of syphilitics and ending the procreation of such subject,” school superintendent Clara C. Patterson wrote in 1929. She requested that “all border-line and feeble-minded girls are sterilized before they are released” as well as “cases where the girl comes under the rating of a ‘moral degenerate.’” It is unknown how many girls were victimized by the sterilization procedure.

Hillcrest was managed by Oregon’s Board of Control, an umbrella agency that included the governor, the secretary of state, and the state treasurer; the state’s juvenile justice system; and policymakers. Following national changes in reform theory and the treatment of incarcerated youth, the board implemented changes in the system beginning in the 1940s. An audit of the school by “an authority of juvenile delinquents,” according to a 1940 issue of the Klamath Falls Evening Herald, concluded that the institution “had an understanding and sympathetic staff but needed expansion of its facilities, staff, and services.” In 1941, the legislature renamed the institution the Hillcrest School of Oregon, and the staff grew to include a part-time psychiatrist, a chaplain, and a director of recreation. Postwar societal shifts brought changes to the Hillcrest School curriculum as well, as the forced agrarian and homemaking focus was modified to concentrate more on education and vocation.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, Hillcrest expanded as youth incarceration rates increased. New facilities were still being constructed in the Cottage Style, with separate bedrooms for each inmate, but changing social ideas and rising juvenile crime rates led to the first maximum-security unit at Hillcrest in 1962. During the same period, Hillcrest offered programs designed to give some incarcerated girls more freedom: they were assigned keys, were allowed to work off-campus, and received more vocational training opportunities. By 1968, 303 girls were affiliated with Hillcrest, with 128 living at the institution and 175 in foster care, in off-campus programs, or on parole.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, boys were allowed to attend classes at Hillcrest. By 1973, it had become a co-ed facility, including the admission of some residents from the MacLaren School for Boys in Woodburn (now the MacLaren Youth Correctional Facility). At the time, Superintendent Charles W. Pfeiffer stated that the activities offered had provided “normal teen-age experience [and] reduced tension and increased morale considerably.”

During the 1980s, a higher percentage of Hillcrest’s residents had committed major crimes. Responding to a change at the federal level, the Oregon legislature blocked courts from incarcerating youth for committing so-called status offenses, such as truancy, running away from home, curfew violations, or underage drinking. Only youth convicted of misdemeanors or felonies could be committed to Oregon training schools. Oregon’s juvenile arrests declined, and the Oregon Children’s Services Division, which had taken over the management of Hillcrest in 1971, reviewed Oregon’s Juvenile Corrections programs. They changed the focus to finding the causes of recurring criminal behavior, enforcing accountability, and transferring funding to aid communities.

Practices changed at Hillcrest during the 1990s, however, as rehabilitative treatments shifted the focus to punishment. Nationwide, juvenile arrests increased dramatically, and young offenders were treated more like adult criminals. In 1995, the legislature passed a wide range of changes to the juvenile justice system, including a reorganization of the treatment and educational services at Hillcrest (by this time known as the Hillcrest Youth Correctional Facility). A new agency, the Oregon Youth Authority, was created to operate the juvenile corrections programs in the state.

Not only were more youth incarcerated during this period, but the establishment of mandatory minimum sentences meant that youth were imprisoned for longer periods of time. By 1997, Hillcrest housed 244 youth offenders—both male and female—in its “secure custody” facility. Physical changes to the campus included the addition of a high-security perimeter fence—the first such fence at the facility—and open floor plans with youths sharing sleeping quarters. At the same time, the state sold large parcels of the Hillcrest School landholdings.

In 2008, Hillcrest became a male-only facility when the Oregon Youth Authority transferred incarcerated females to the Oak Creek Youth Correctional Facility in Albany. Most of the youth at Hillcrest were held in long-term treatment units, and treatment-based programming increased over time as a focus on punitive measures decreased.

By the 2010s, the facility needed extensive seismic upgrades and required costly changes to create the housing and treatment environment favored by the state’s juvenile justice system, including a return to single-occupancy bedrooms. The Hillcrest Youth Correctional Facility was closed in 2017, and incarcerated youth were moved to other facilities, including MacLaren. The State of Oregon sold the Hillcrest facility and grounds in 2020.

-

![]()

Hillcrest Youth Correctional Facility.

Oregon Youth Authority

-

![]()

English class, Hillcrest, 1959.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Monner, photo file 931D

-

![]()

Typing class, Hillcrest, 1959.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Monner, photo file 931D

-

![]()

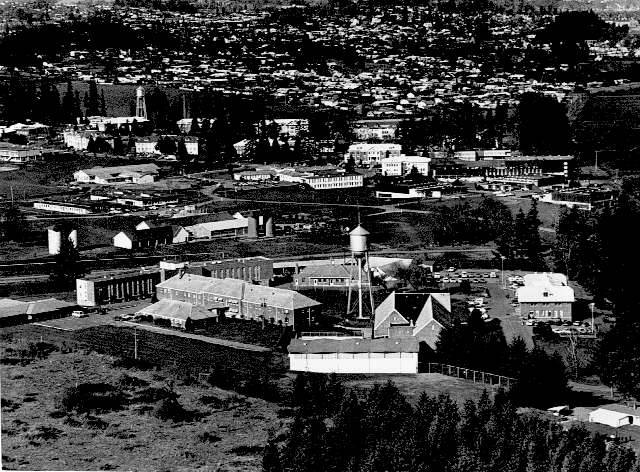

Hillcrest School (foreground), Salem.

Courtesy City of Salem Historical Photograph Collection

Related Entries

-

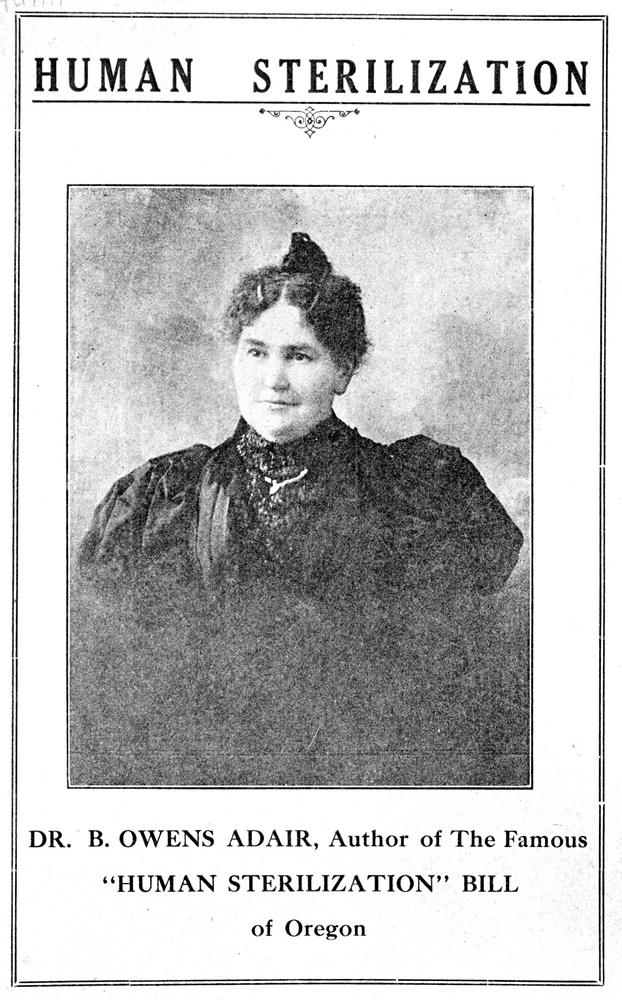

![Bethenia Owens-Adair (1840-1926)]()

Bethenia Owens-Adair (1840-1926)

Bethenia Owens-Adair overcame seemingly insurmountable obstacles to bec…

-

![MacLaren Youth Correctional Facility]()

MacLaren Youth Correctional Facility

The MacLaren Youth Correctional Facility in Woodburn is one of five cor…

-

![Oregon Anti-Sterilization League]()

Oregon Anti-Sterilization League

The Oregon Anti-Sterilization League, formed in February 1913 at the Ea…

-

![Oregon State Penitentiary]()

Oregon State Penitentiary

The Oregon State Penitentiary, Oregon's only maximum-security prison, s…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Grant, Julia. The Boy Problem: Educating Boys in Urban America, 1870–1970. Baltimore. MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014.

“Has Practical Plan for Girls.” Salem Daily Oregon Statesman, January 11, 1914, p.13.

Smolensky, Jack. “A History of Public Health in Oregon.” PhD thesis, University of Oregon, June 1957.

McBride, Marjorie Grace. “A Historical Study of the Administrative Structure of Hillcrest School of Oregon.” PhD thesis, Oregon State University, June 1973.

"Oregon School Criticized by Osborne Group.” Klamath Falls Evening Herald, November 12, 1940, p.10.

"Oregon’s Juvenile Corrections Programming: A New Direction." Oregon Children’s Services Division, Department of Human Resources, December 17, 1982.