From Oregonian Stewart Holbrook's first book through his three dozen later volumes, he made clear that he was not writing academic history. His aim was to be a storyteller, with emphases on stirring narrative, lively pen portraits, popular artworks, and dramatic events. He was writing, he said, “lowbrow” or “non-stuffed shirt history.” In his early newspaper stories, in popular magazines, and in dozens of books published from 1938 to his death in 1964, Holbrook endeavored to write popular, dramatic histories for lay audiences. He was eminently successful in reaching that goal.

Born in Newport, Vermont, on August 22, 1893, Stewart Holbrook attended high school in New Hampshire, remaining in New England through his early twenties. He arrived in Oregon in 1923, broke and without a job, but soon found work as a log scaler and river logger. He also began writing essays for the general public in Lumber News, the Portland Oregonian, and the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen’s 4-L Bulletin.

In 1938, Macmillan, a New York publisher, issued Holbrook’s first major book, Holy Old Mackinaw: A Natural History of the American Lumberjack, an account of his lifetime interest in loggers, lumbermen, and forests that remained on best-seller lists for five months. The book provides hints about his style of writing and demonstrates his storytelling power, his adept use of biographical vignettes, and the gusto of his plenteous descriptions. After reading Holy Old Mackinaw and some of his later books on loggers, readers began to refer to him as a “Lumberjack Boswell.”

Lost Men of American History (1946) illustrates Holbrook's interest in persons lost or overlooked in American history. Christopher Ludwick, David Bushnell, and Mrs. Bloomer may have been forgotten as a banker, inventor, and clothier for women, but Holbrook shows how their efforts illustrate the genius of many Americans who have been omitted from the nation's historical accounts.

Holbrook also wrote a good deal about the so-called demigods of the American West, including Annie Oakley, Calamity Jane, Wild Bill Hickok, and Wyatt Earp. These biographical accounts were popular with thousands of readers; but factual errors, limited research in obscure sources, and missing interpretive frameworks meant they are not the best of Holbrook's books. He most diligently researched The Yankee Exodus: An Account of Migration from New England (1950), in which Holbrook tells the story of his migration from New England to the West Coast. Referring to more than two thousand personal names, Holbrook ransacked local and manuscript sources to trace these journeys westward.

Holbrook was a master of journalistic overviews rather than of more narrowly focused, analytical studies. His Story of American Railroads (1947), The Age of Moguls (1953), and The Columbia (1956) are appealing examples of his talent for interest-whetting storytelling. Critics of his writing had reservations, however, convinced that he too often sacrificed broad-based research and historical accuracy to create lively stories.

In his works on logging and forestry, Holbrook addressed issues of concern to conservationists and environmentalists. In the spectrum of opinion on these controversial issues, he stood more with “wise use” advocates such as Theodore Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot than with wilderness supporters such as John Muir and the Sierra Club. Holbrook’s middle-of-the-road views called for the careful use of forest products and the avoidance of too much clear-cutting, but he also believed that loggers and lumbermen deserved to continue their work so they could support their families. Holbrook did not favor locking up natural resources.

The energetic Holbrook turned to painting in the 1950s. Encouraged by his wife Sybil and working under the pseudonym of “Mr. Otis,” Holbrook began producing what some called “civilized primitive” artworks. Like most of his writings, he considered his painting to be “lowbrow” art.

Stewart Holbrook died in Portland on September 3, 1964, from a cerebral vascular hemorrhage, and was buried in Willamette National Cemetery. He was survived by Sybil Holbrook, whom he had married in 1948, and two daughters. Over the years, he had lived in Boston and Seattle but primarily in Portland.

Seen whole, Holbrook’s career illustrates the successful journey of a journalist and narrative historian who based his tales on the obscure and unknown rather than on the rich and famous.

-

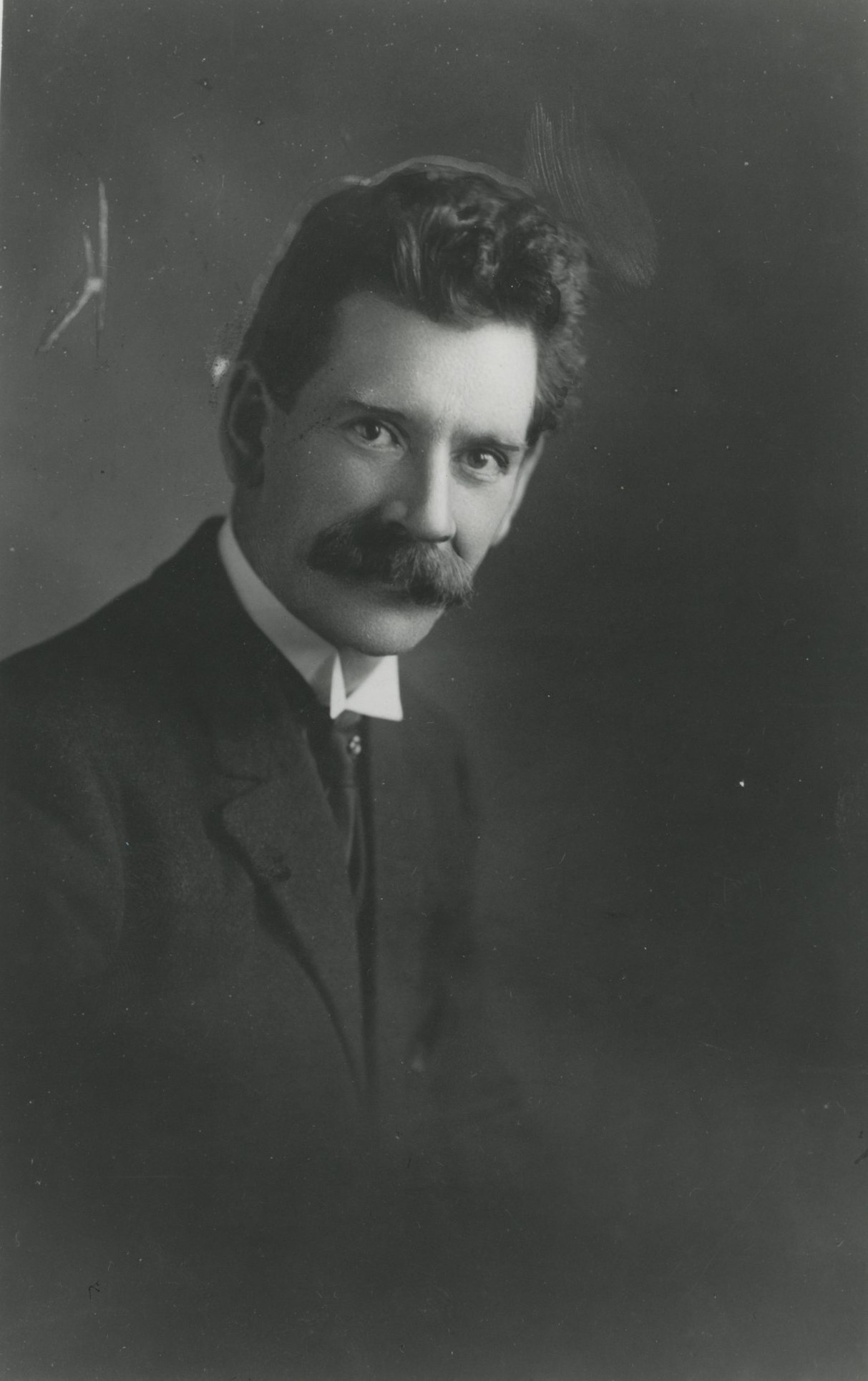

![]()

Writer Stewart Holbrook, 1940.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, Orhi80357

-

![]()

Holy Old Mackinaw, by Holbrook.

Courtesy Comstock Publishing

-

![]()

The Columbia, 1956.

Courtesy Rinehart and Co. Press

-

![]()

Wildmen, Wobblies & Whistle Punks.

Courtesy Oregon State University Press

-

![]()

Stewart Holbrook. Team of workhorses drawing sledge load of logs on muddy road..

Courtesy University of Oregon Libraries -

![]()

Stewart and Sybil Holbrook with friends, 1955.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 010054

-

![]()

Stewart Holbrook and writer Ellis Lucia, 1959.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 012392

-

![]()

The Lost Doll, painting by Stewart Holbrook, 1951.

Oregon Historical Society Museum Collections, 2024-24.1

Related Entries

-

![Benson Bubblers]()

Benson Bubblers

At the turn of the twentieth century, logging magnate Simon Benson was …

-

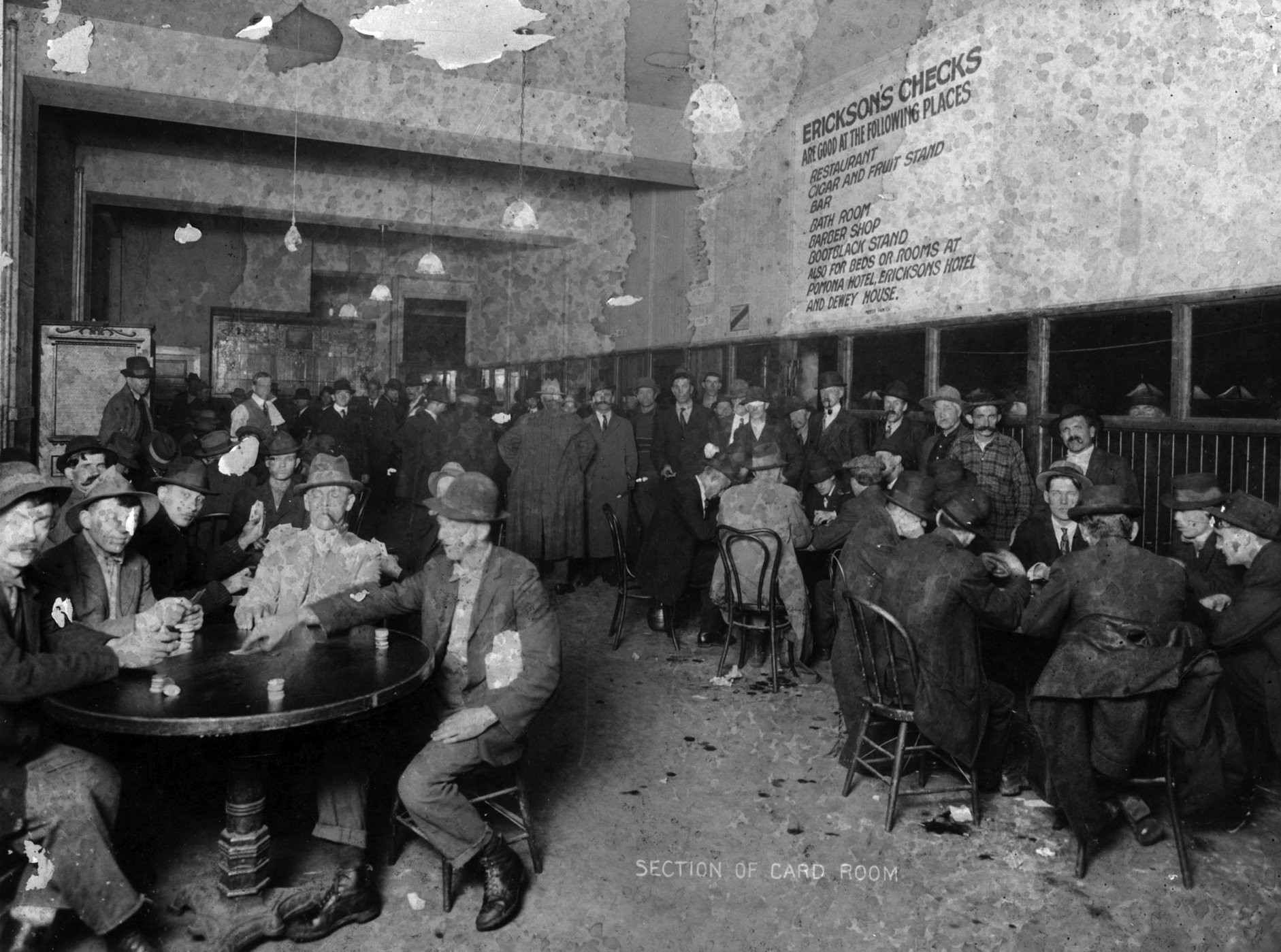

![Erickson's Saloon]()

Erickson's Saloon

Erickson’s Saloon, sometimes called the Working Man’s Club or The Erick…

-

![Nard Jones (1904-1972)]()

Nard Jones (1904-1972)

Nard Jones—novelist, historian, and journalist—wrote prolifically about…

-

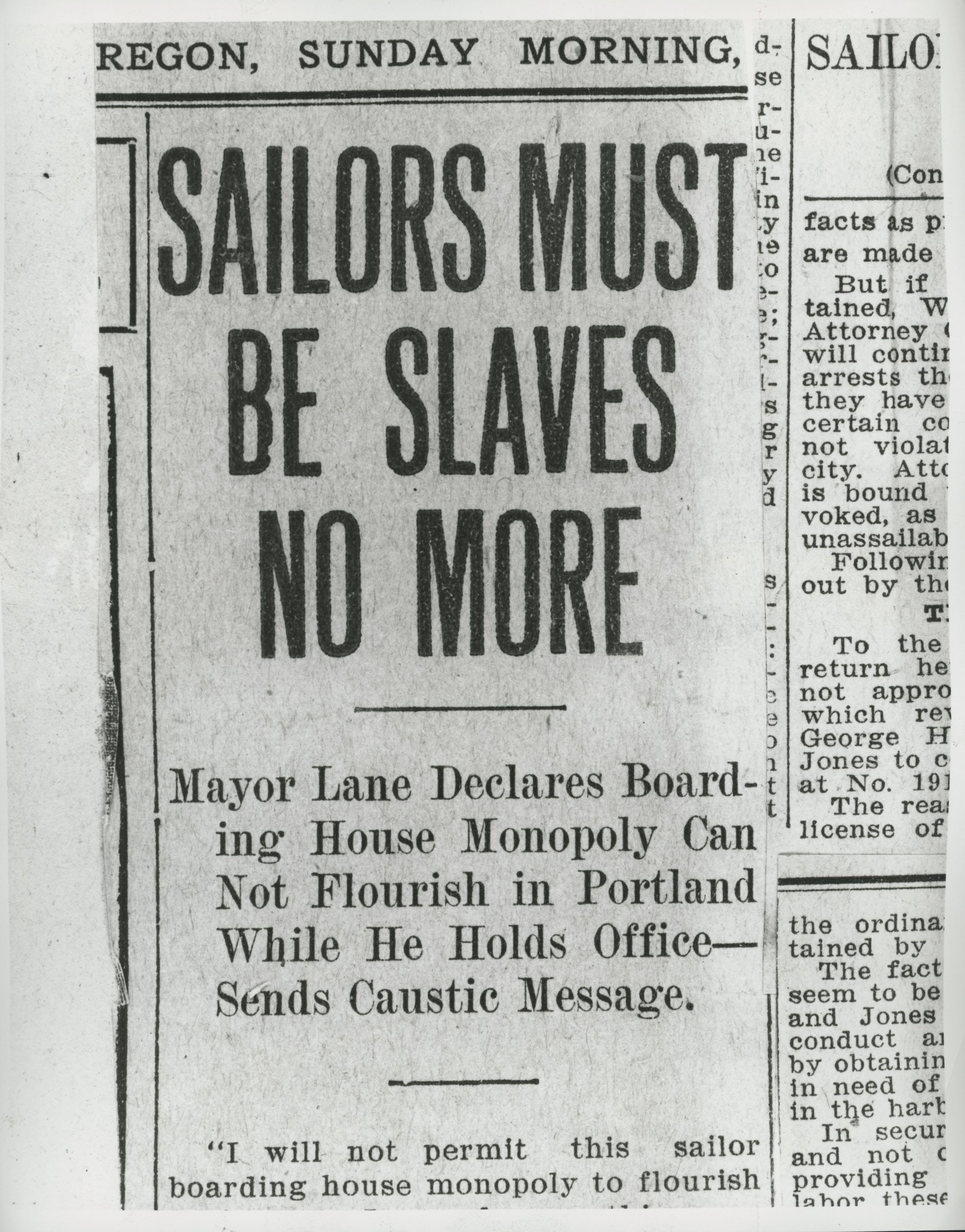

![Shanghaiing in Portland and the Shanghai Tunnels Myth]()

Shanghaiing in Portland and the Shanghai Tunnels Myth

Since the 1970s, a myth has grown up that propounds the existence of a …

-

![The Oregonian]()

The Oregonian

The Oregonian, the oldest newspaper in continuous production west of Sa…

-

![Thomas Joseph Burns (1876-1957)]()

Thomas Joseph Burns (1876-1957)

In his fifty-two years in Oregon, Tom Burns threw himself into nearly e…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Booth, Brian, ed. Wildmen, Wobblies and Whistle Punks: Stewart Holbrook's Lowbrow Northwest. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1992.

Gastil, Raymond D., and Barnett Singer. The Pacific Northwest: Growth of a Regional Identity. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2010.

Holbrook, Stewart H. Far Corner: A Personal View of the Pacific Northwest. New York: Macmillan Company, 1952.

----,.Promised Land: A Collection of Northwest Writing. New York: Whittlesey House, 1945.