The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or "Wobblies"), founded in 1905 and crushed for its opposition to World War I in 1917-1918, was the most active and most actively opposed revolutionary union of its time. In Oregon, the IWW was rooted in lumber camps and mills in the western part of the state and among field hands in eastern agricultural areas. Working conditions were poor in those industries, and employers strenuously fought unionization, particularly by the IWW, which refused to make agreements with capitalists and advocated sabotage on the job.

The IWW first appeared in Oregon in early 1907, when the union led a Portland parade of its members in protest against the trial of IWW leader William D. Haywood, who had been falsely charged with the 1905 murder of Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg. Portland remained the center of IWW activity in Oregon, and members spoke on street corners to organize rural laborers who came to the city in the off-season or to find work from employers’ agents. The mainstream Portland unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) quickly distanced themselves from the IWW and its largely unskilled and itinerant constituency.

The IWW had its Oregon headquarters in Portland’s North End, a neighborhood near downtown that was densely populated with poor men and home to much of the city’s vice. The union and its members became associated with crime and raucous immorality by the sensationalist attention paid to the neighborhood in the local press. The itinerant workers who sometimes called the North End home did much to build IWW culture in Oregon, and that culture shared the neighborhood's fate. Political pressure swept the brothels out of the North End in 1913 and closed the saloons in 1916. Finally, the IWW lost its meeting hall after the state passed a criminal syndicalism law in 1919 that made revolutionary organizing illegal.

By conducting most of its organizing on the streets, in contrast to the shop-floor campaigns of the AFL, the IWW gained a deserved reputation for being disruptive. In 1912, for example, IWW activists heckled Robert Baden-Powell, the founder of the Boy Scouts, while he spoke to a large and otherwise admiring crowd in Portland. During a cannery strike in the summer of 1913, the city government and its police force repeatedly jailed IWW members in order to halt public protests. The protests were one of the “free speech fights” the union organized in the region, when they would call in outside reinforcements to fill a town’s jail until authorities gave up and allowed them to speak publicly.

In the summer of 1917, during the first months of the nation’s mobilization for World War I, the federal government became alarmed by the growing unrest in Pacific Northwest lumber camps and sawmills led by the IWW. The region's logging then came under the control of the U.S. Army. Workers joined the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen, a compulsory paramilitary union. Wartime sedition laws and their enforcement by the FBI, Military Intelligence, and police “red squads” also left the IWW much diminished.

The IWW never recovered and Communist groups eclipsed it after the war, but the organization still left a profound legacy in Oregon. Its members were among the first activists in the state to practice civil disobedience and to willingly endure repeated jail terms in defense of their civil liberties. The union still has a small national membership today, with branches in Eugene and Portland.

-

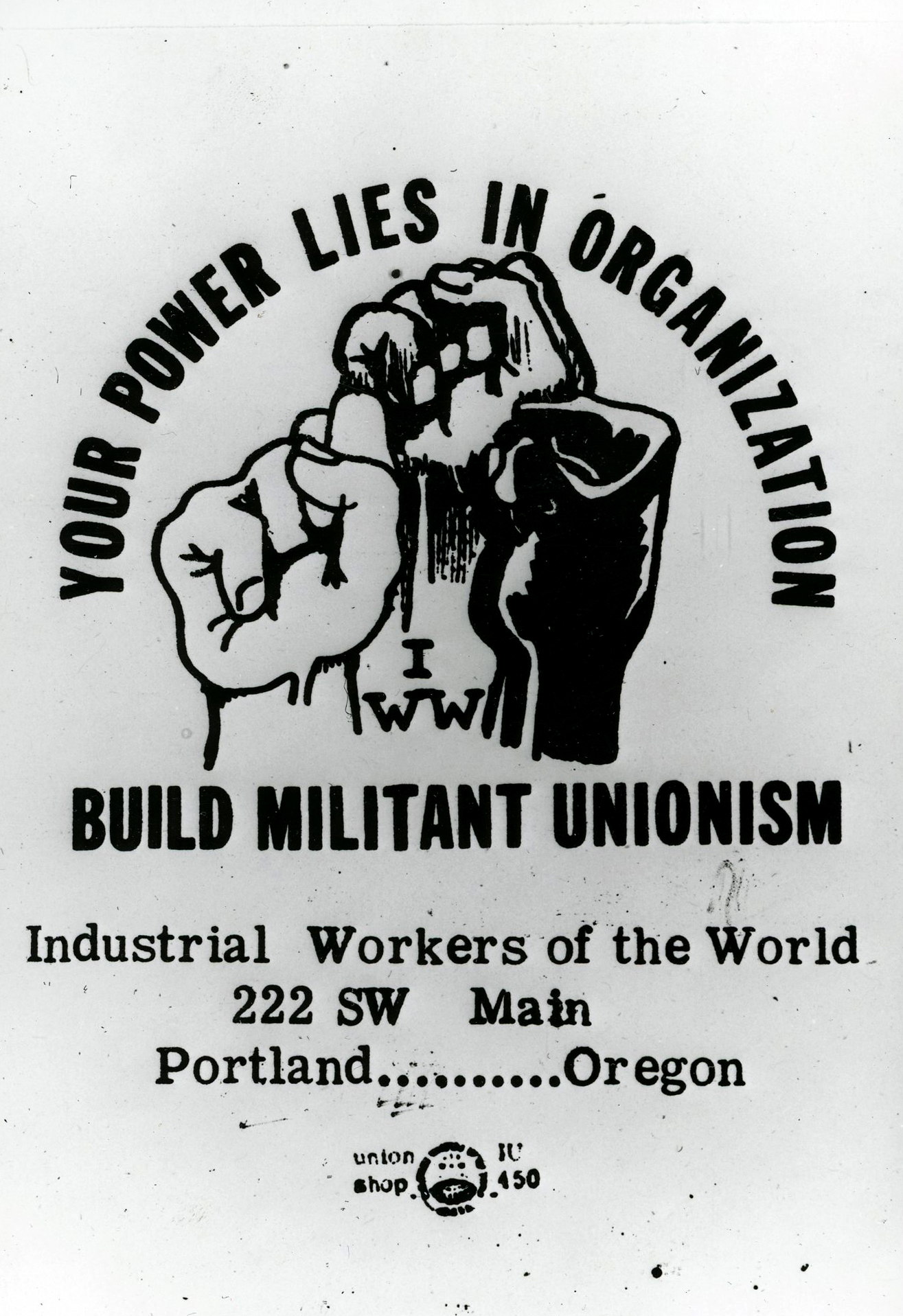

![]()

IWW poster.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi77728

-

![The men were accused of blowing up Bunker Hill Mine and murdering Gov. Steunenberg; they were defended by Clarence Darrow.]()

George Pettibone, William Haywood, and Charles Moyer.

The men were accused of blowing up Bunker Hill Mine and murdering Gov. Steunenberg; they were defended by Clarence Darrow. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 945 f1

-

![]()

Governor of Idaho, Frank Steunenberg, c.1900.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 945 f1

-

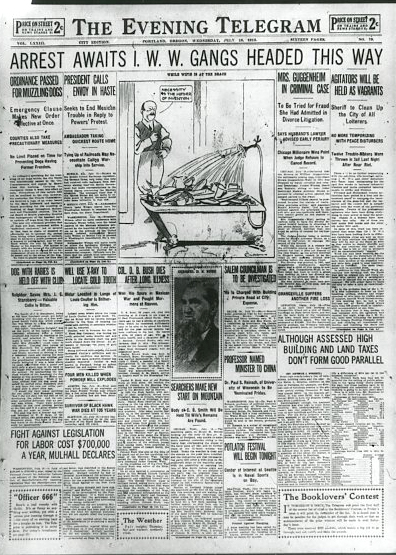

![]()

Portland Evening Telegram front page, July 16, 1913.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi77733

-

![]()

An early issue of the Spirit of the Times, an IWW publication.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Pam331 886142i

-

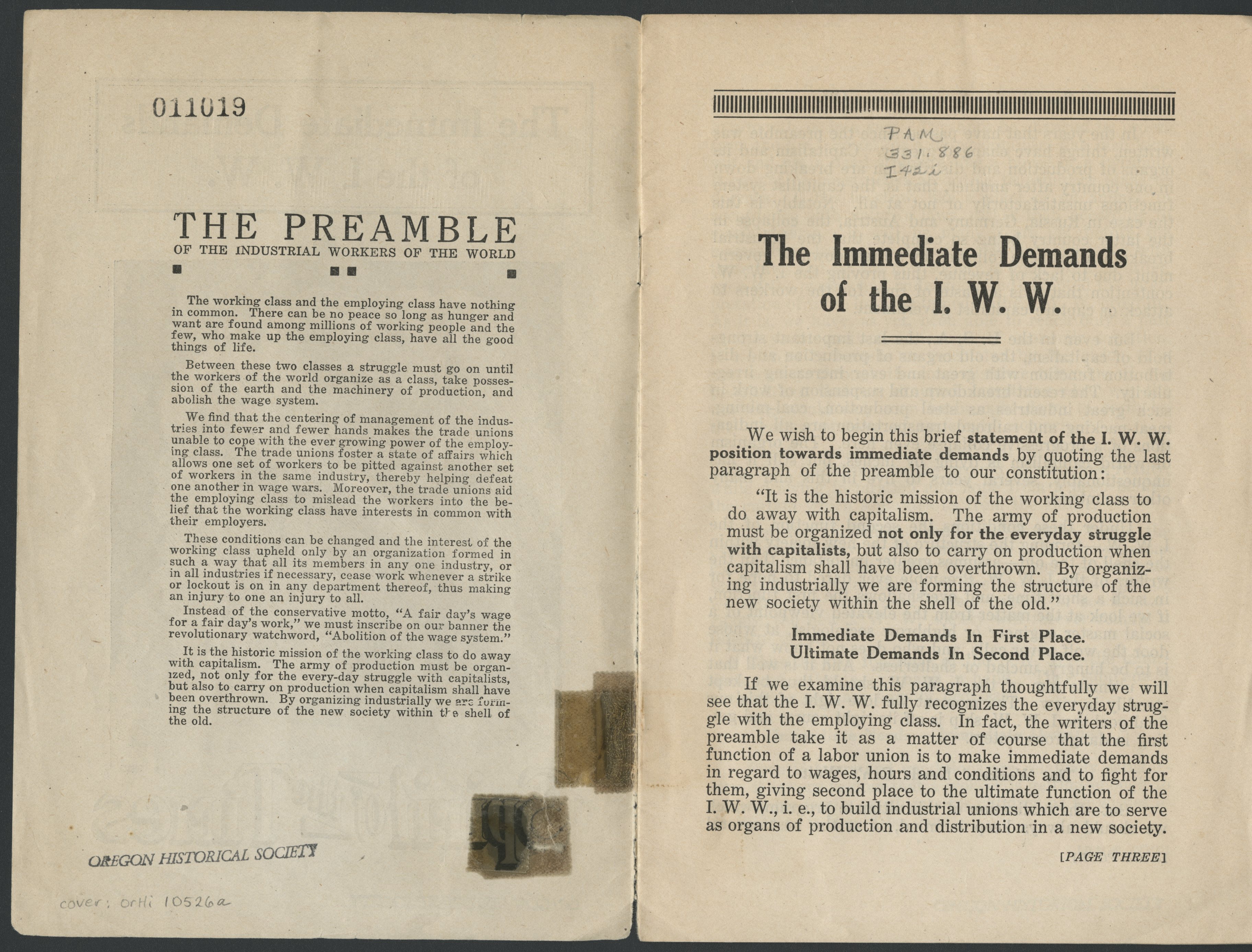

![First pages.]()

An early issue of the Spirit of the Times, an IWW publication.

First pages. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Pam331 886142i

-

![]()

IWW strike committee, Astoria, 1948.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 85067

-

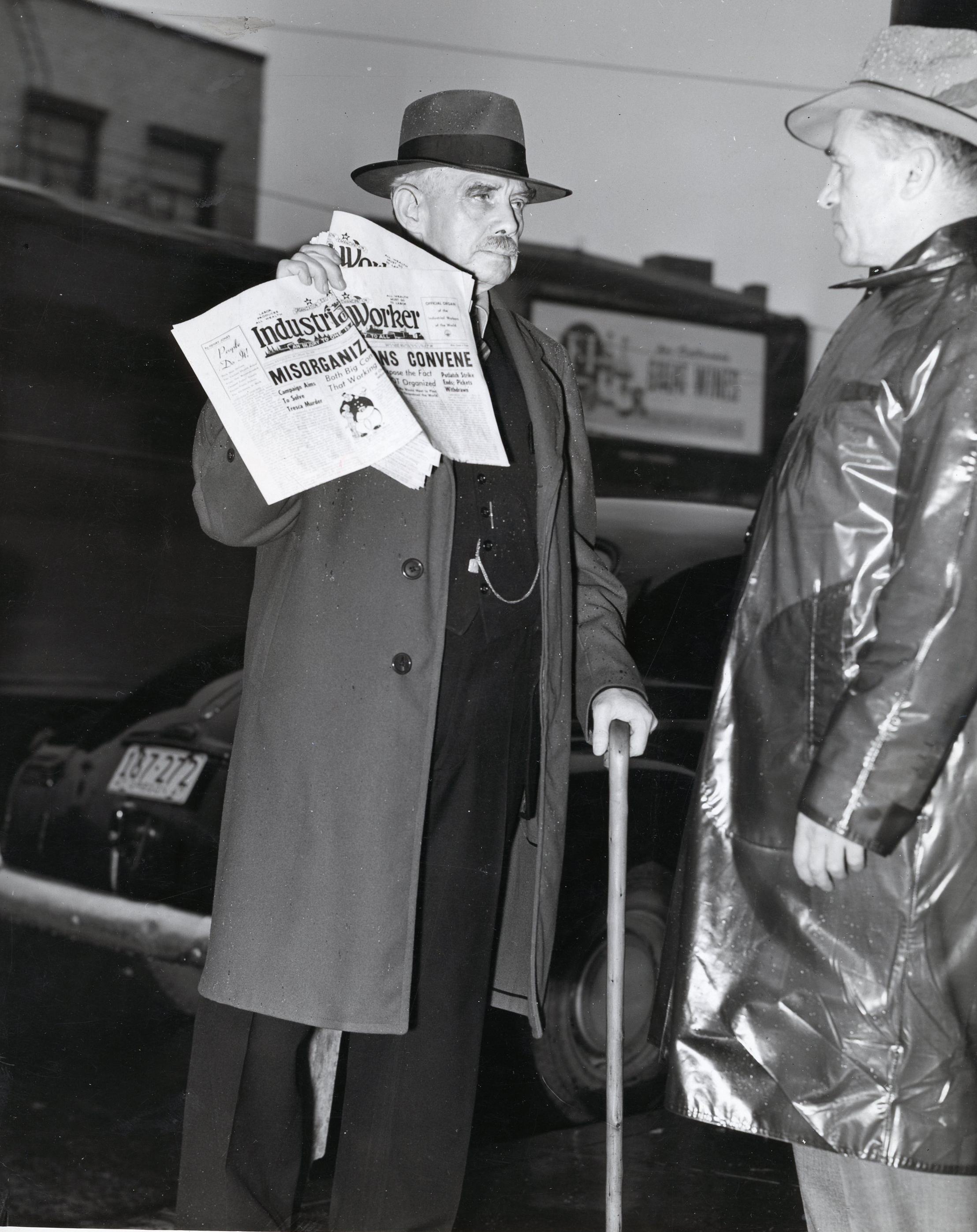

![Boose retired to Portland.]()

Wobbly Arthur Boose and Stewart Holbrook in 1959.

Boose retired to Portland. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 10695

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Dubofsky, Melvyn. We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World. Second Edition. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988.

Hall, Greg. Harvest Wobblies. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2001.

Tyler, Robert L. Rebels of the Woods: The I.W.W. in the Pacific Northwest. Eugene: University of Oregon Books, 1967.