On Sunday, September 20, 1942, nearly a thousand residents of Klamath Falls clashed with a group of Jehovah’s Witnesses attending their state convention in a large garage at Ninth and KIamath Streets. The Klamath Falls Herald and News described what it called the Klamath Falls Jehovah’s Witness Riot as “an unprecedented local incident” of group violence. The confrontation was evidence of the intense wartime anger many people held against those they considered to be “disloyal”—both the Japanese and Japanese Americans who had been rounded up for incarceration and “traditional” (that is, white) Americans who refused on religious grounds to serve in the military or to support the war effort.

Across the country, Jehovah’s Witnesses had refused to pledge allegiance to the American flag and to submit to military draft after the nation’s entry into World War II. Local draft boards often denied conscientious objector status to male, draft-age Witnesses. The Witnesses had a history of such dissent. During World War I, for example, some Witnesses had been jailed for speaking out against the war; and in the 1920s and 1930s, their anti-Catholic rhetoric and condemnation of Protestant churches as “rackets” had contributed to their reputation for being among the most unpopular religious groups in the country.

By September 1942, feelings against Jehovah’s Witnesses were further inflamed by newspaper coverage of the mistreatment of American prisoners during the Bataan Death March in the Philippines. Three days before the Klamath Falls convention, local residents reportedly became irked and then angered by the Witnesses’ pamphleteering campaign on downtown streets. American Legion members and others baited Witnesses for refusing to salute the flag or buy war bonds.

On the last day of the conference, the Witnesses’ national leader N. J. Knorr was scheduled to speak to the conference by telephone from Cleveland, Ohio. Townspeople gathered outside the meeting place, and a war-bonds sales booth was placed just outside, where a loudspeaker truck played a recording of the “Star-Spangled Banner.” People on the sidewalk shouted through the windows for the Witnesses to stand up for the national anthem.

In order to silence Knorr's speech, several war veterans attempted to cut the phone line. A number of Witnesses, alerted to the threat, came out the rear door, reportedly armed with clubs and sticks, and a fight ensued. At least three Klamath Falls residents were injured seriously enough to be taken to the hospital. The violence spread as the protesters broke the garage’s windows, tore down banners, and burned stacks of the Watchtower and other church literature in the street. Some in the crowd hurled eggs and “stench bombs” through the broken windows.

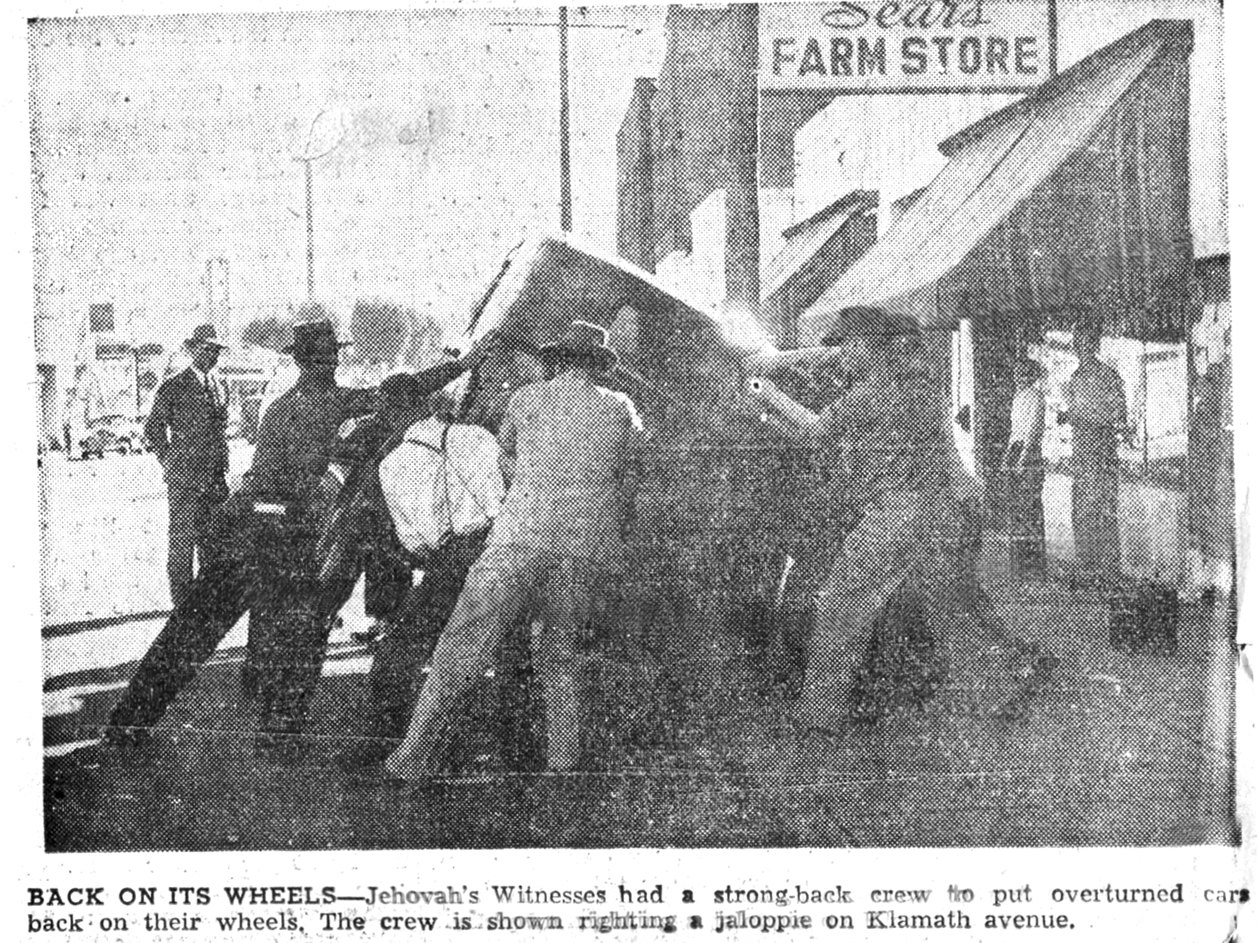

The Portland Oregonian reported that a mob of men and boys “turned over nearly 100 automobiles owned by the Witnesses” (the actual number was fewer than two dozen). Others broke into the local Witnesses’ headquarters, piled furniture outside, and set a second fire. A pregnant member of the church, experiencing labor pains, was rushed from the garage by uniformed members of the Women’s Ambulance Corps.

Klamath Falls police chief Earl Heuvel called out his entire force, including reserve officers. To protect the women and children inside the garage, the police set off a tear-gas shell outside. Charles Cook, a Marine recruiting sergeant and former city police judge, mounted the sound truck and urged the crowd to disperse, reporting that Oregon Governor Charles Sprague had urged that calm be restored.

Cook’s plea took effect. Jehovah’s Witnesses left the garage under police guard and, after their cars had been righted by a “strong back” crew of churchmen, drove out of town. During the same week, vigilantes beat Witnesses in Texas, and fights between Jehovah’s Witnesses conventioneers and war-emergency pipeline workers in Little Rock, Arkansas, sent seven people to the hospital, two with gunshot wounds.

Following the war, court cases established the constitutional right of Jehovah’s Witnesses not to salute the flag and to be exempt from the military draft as conscientious objectors. The Klamath Falls episode is a reminder of the powerful feelings against minorities, especially during times of war.

-

![]()

Jehovah's Witnesses riot, 1942.

Courtesy Klamath Falls Herald

-

![]()

Aftermath of the Jehovah's Witnesses riot in Klamath Falls.

Courtesy Portland Oregonian

Related Entries

-

![Civilian Public Service Camp #21]()

Civilian Public Service Camp #21

Civilian Public Service Camp #21 opened in November 1941 at Wyeth, a fe…

-

![Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon]()

Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon

Masuo Yasui, together with many members of Hood River’s Japanese commun…

-

![Quakers in Oregon]()

Quakers in Oregon

Quakerism as a religious denomination came to Oregon in the 1870s, when…

-

![Untide Press]()

Untide Press

The Untide Press (1943-1951) was a small poetry press founded at Camp A…

-

![William Stafford (1914-1993)]()

William Stafford (1914-1993)

William Stafford, one of America’s most widely read poets, was born in …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Yates, Richard. "Klamath Falls Goes to War: A Personal and Newspaper Reminiscence." Oregon Historical Quarterly 107.3: 2006.