The town of Jordan Valley stretches along Highway 95 in Oregon’s High Desert. At an elevation of 4,385 feet, the town is on the north side of Jordan Creek, a tributary of the Owyhee River. Located on a volcanic plateau, Jordan Valley was shaped by volcanic eruption about 150,000 years ago. Jordan Craters, about thirty miles to the north, is a volcanic field that exhibits pahoehoe basalt, dark basalt characterized by a smooth, billowy, or ropy surface. Mining and ranching form the economic foundation of the town and the surrounding area.

The Northern Paiute, traditionally semi-nomadic bands, traveled to the mountains or streambeds near present-day Jordan Valley to follow food sources, gathering nuts, fruits, berries, and eggs and hunting deer, geese, and bear. After encounters with white settlers, competition for resources led to the Snake War (1864-1868), a series of skirmishes in which 1,762 men were killed, wounded, or captured on both sides. The war and the removal of Natives to a reservation in 1868 resulted in the death of two-thirds of the Northern Paiute people.

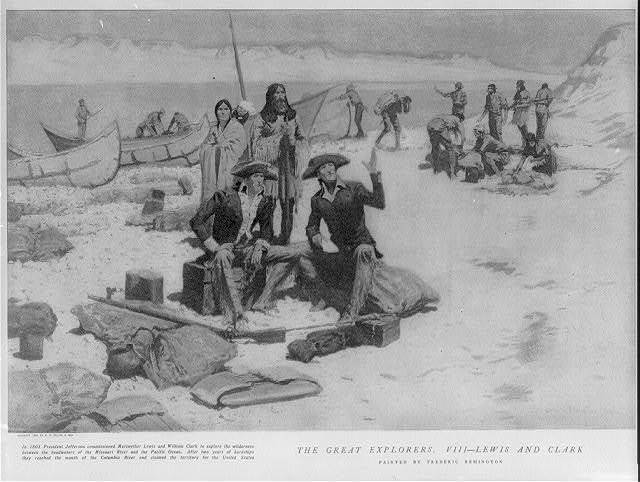

Non-Native settlement in the area began with the discovery of gold in May 1863 along Jordan Creek, a tributary of the Owyhee River that was named for Michael M. Jordan, the mining party’s leader. Placer mines, underground mines, and mills in the Owyhee watershed yielded $40 million in gold and silver over the next fifty years. Among the early miners was Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, who had been on the Lewis and Clark Expedition as a child and traveled to the area from California. He died of pneumonia in May 1866 and is buried at Inskip Stage Station (present-day Danner).

In 1865, Silas Skinner built a toll road to pack in supplies for miners and to transport gold and silver to the West Coast. The road began in Ruby City, Idaho, a mile from Silver City, a booming mining community in southwestern Idaho's Owyhee Mountains. Continuing to Trout Creek and through the town of Jordan Valley to Ruby Ranch, sixteen miles to the west, the road ended at Duncan’s Ferry at the junction of Jordan Creek and the Owyhee River. Workers dug the road by hand and in several places cut or blasted through lava (portions of the road lie under Highway 95).

The Skinner Toll Road, which opened on May 19, 1866, connected to a road to Chico, California, and then to San Francisco; freight could be transported between Silver City and Chico in a week. Contemporaneously, Skinner and a partner finished the Reynolds Creek Road, a toll road that extended from Ruby City north toward the Snake River, where freight could be floated on the Columbia River to the coast. Gradually, more traffic from Silver City traveled the Skinner Toll Road and on the Sacramento River than on the Columbia.

The town of Jordan Valley was established along the Skinner Toll Road about three miles west of the Idaho state line. Among the first residents was John Baxter, whose cabin served as an inn, store, and post office, established on February 13, 1867. Miners stopped in the town on their way to boomtowns such as Silver City and DeLamar, a few miles to the east in present-day Idaho. The town was also known as Stringtown because the earliest buildings were built along the road; Dog Town due to the dogs running loose in the town; and Baxterville, after John Baxter. Jordan Valley was incorporated on March 21, 1911.

While the population in Silver City and other boomtowns declined when the mines began to fail in 1875, Jordan Valley survived because of cattle ranching. The public land in southeastern Oregon provided range for stock and encouraged large herds of cattle and sheep. Eleven ranches were operating in the Jordan Valley area by 1867, and local cattleman Cornelius “Con” Shea drove Texas Longhorns to the area two years later.

The earliest Basques in Jordan Valley were probably Antone Azcuenaga and José Navarro, who arrived in 1889, initiating an immigration pattern that was repeated by Basques over the next forty years. Recent immigrants signed on as sheepherders for local ranchers. The herders, who generally knew no English, worked alone, living in sheepherder wagons and staying in one of three Basque boarding houses when they were in town and, after 1915, playing handball on the pelota fronton court. Many herders eventually acquired ranches, and those who returned to their native Basque province to marry often encouraged younger relatives to emigrate. By the 1920s, Basques comprised about two-thirds of Jordan Valley’s population of 355. Although admired for their industrious, honest, and hard-working way of life, Basques occasionally fell victim to discrimination as the most recent non-English-speaking immigrants in the area.

This pattern was interrupted after the Taylor Grazing Act, passed in 1934, required permits that favored those ranchers who did not need the use of rangeland in all seasons. With that change, immigration of Basques to the area slowed, and cattle replaced sheep on the range. The economy of Jordan Valley is now based on cattle ranching and wheat and grain farming.

Jordan Valley’s population was about 376 in 1990. Between 1993, when the Kinross DeLamar Mine reopened, and 1999, when the mine closed, the population grew to 446 (the town had 376 residents in 1990). By 2016, Jordan Valley had a population of about 130 residents. Tourism continues to be important to the area, with visitors attending the annual Jordan Valley Big Loop Rodeo, exploring historical sites and geological features, rafting on the Owyhee River, and fishing and hunting.

-

![]()

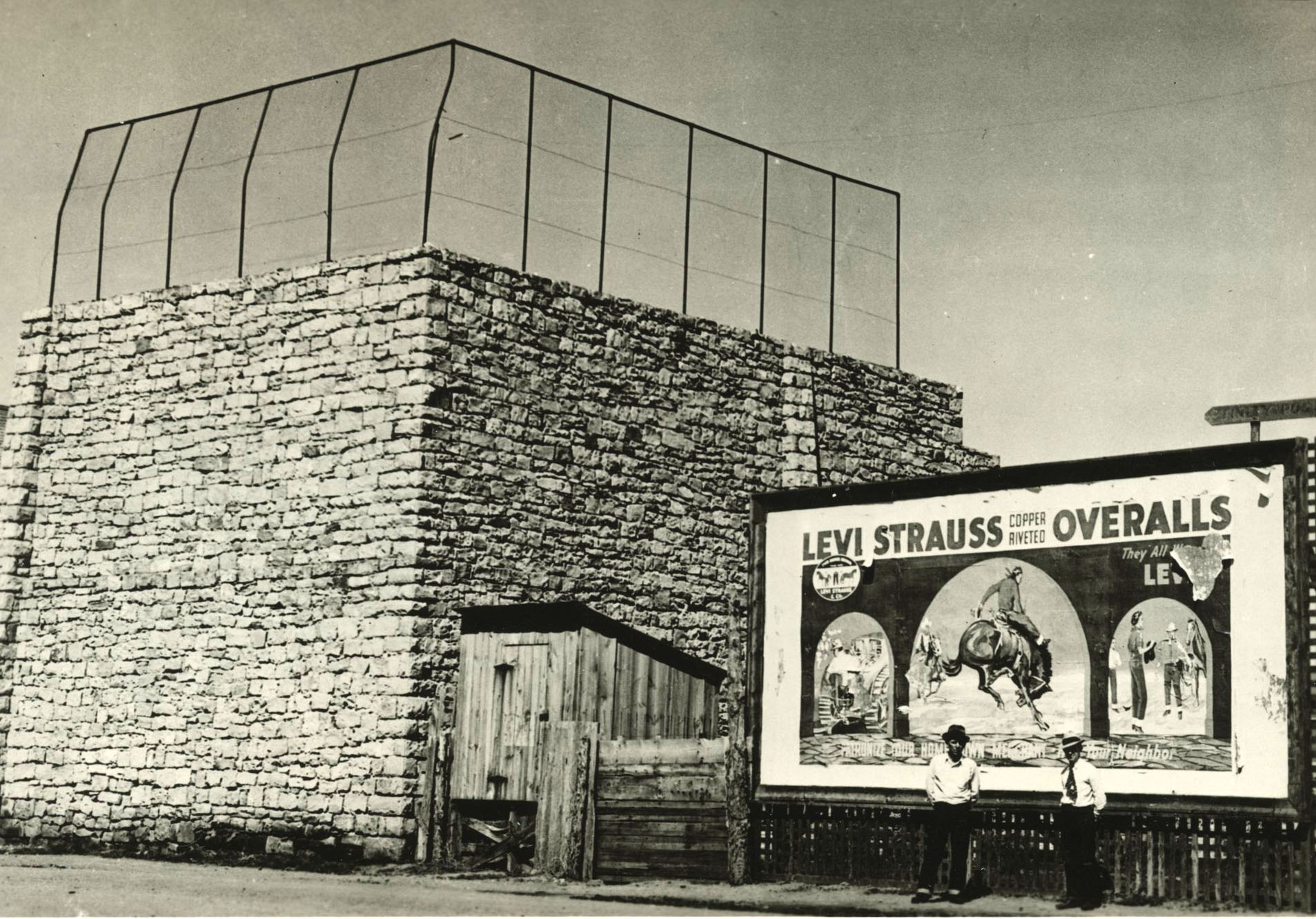

Jordan Valley, 1970.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 82660

-

![]()

Jordan Valley, 1959.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., photo file 594

-

![]()

Jordan Craters, south of Owyhee Lake.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 981d132

-

![]()

Jordan Valley handball court (pelota fronton), 1938.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., WPA, Jessie Williams, 45434

-

![]()

Sheep ranch, Jordan Valley.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 93341

-

![]()

Sheepherding near Jordan Valley, 1914.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 23965

-

![]()

Joe Navarro and Pascal Eiguren on their Owyhee Ranch, c. 1914.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 23971, from Fred Eiguren

-

![]()

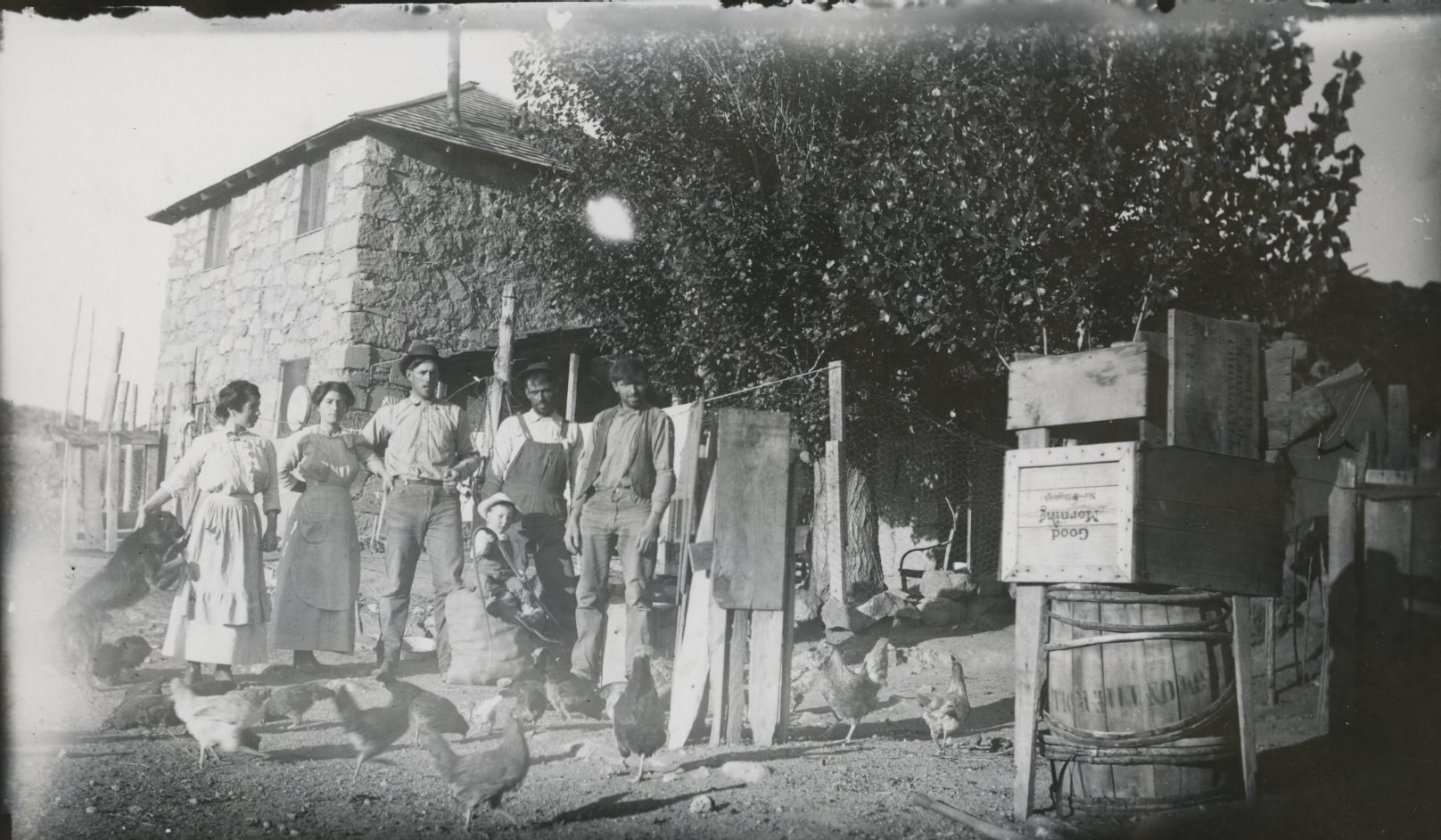

Basque residents, Jordan Valley.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 38052, photo by Eiguren

-

![]()

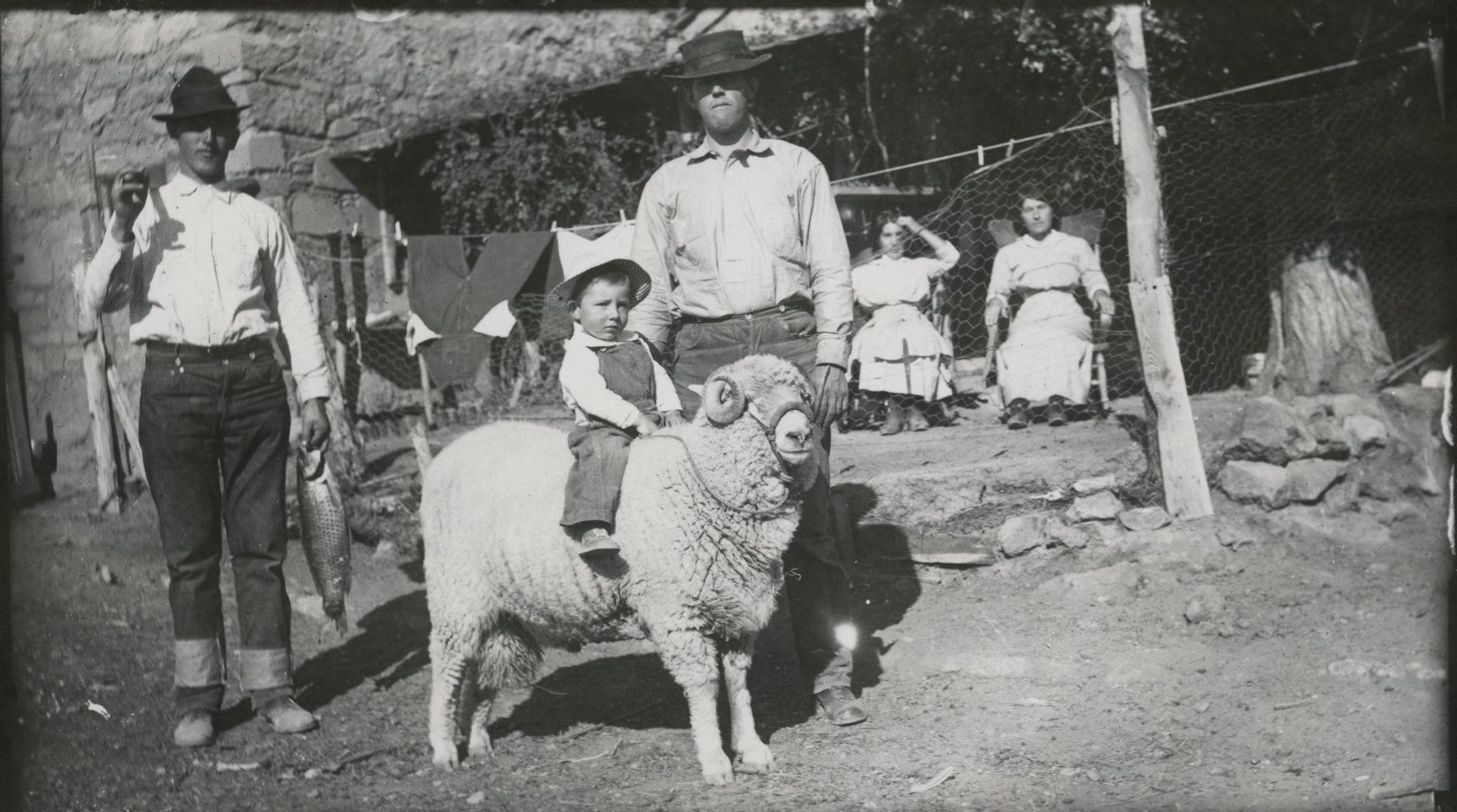

Basque residents of Jordan Valley, c. 1914.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 21730

Related Entries

-

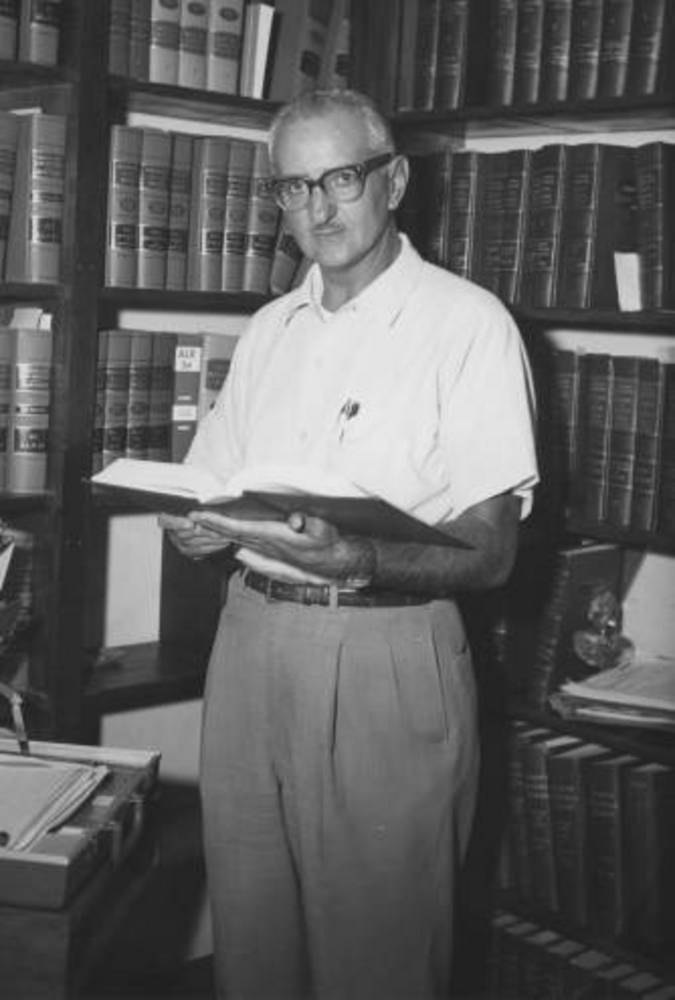

![Anthony Yturri (1914–1999)]()

Anthony Yturri (1914–1999)

Anthony "Tony" Yturri, the son of Basque immigrants, served sixteen yea…

-

![Basque boardinghouses in Oregon]()

Basque boardinghouses in Oregon

Oregon’s earliest Basque settlers arrived in the late 1880s from northe…

-

![Basques]()

Basques

The first Basques to Oregon arrived in the late 1880s. These Euskalduna…

-

![Elden Francis Curtiss (1932-)]()

Elden Francis Curtiss (1932-)

Elden Francis Curtiss, the only native-born Oregonian who attained the …

-

![High Desert]()

High Desert

Oregon’s High Desert is a place apart, an inescapable reality of physic…

-

![Jean Baptiste Charbonneau (1805-1866)]()

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau (1805-1866)

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau is remembered primarily as the son of Sacagaw…

-

![Pelota Fronton]()

Pelota Fronton

The pelota fronton in Jordan Valley is a handball court built by Basque…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Baker, Sarah Catherine. Basque American Folklore in Eastern Oregon, MA Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, 1973.

Baker, Sarah Catherine. “Basque Folklore in Southeastern Oregon.” Oregon Historical Quarterly (June 1975): 153-74.

Berg, Laura, ed. The First Oregonians. Portland: Oregon Council for the Humanities, 2007.

Bishop, Ellen Morris. In Search of Ancient Oregon: A Geological and Natural History. Portland, Ore.: Timber Press, 2003.

Etulain, Richard. Basques of the Pacific Northwest. Pocatello: Idaho State University Press, 1991.

Hanley, Mike, with Ellis Lucia. Owyhee Trails. Caldwell, ID: The Caxton Printers, Ltd., 1973.

Oregon: End of the Trail. Compiled by the Workers of the Writers’ Program of the Work Projects Administration in the State of Oregon, American Guide Series. Portland: Binford & Mort, 1940. (Revised 1951.)

Peterson, Stacy. "Silas Skinner's Owyhee Toll Road." In Idaho Yesterdays (Spring, 1966), reprinted at: http://www.skinnerfamilynw.org/history/Skinner%20Toll%20Road.htm

“The Skinner Road,” Idaho State Historical Society Reference Series, May 24, 1966.