Keiko, a male orca (orcinus orca) originally captured in 1979 from a pod in Iceland, lived in Oregon for less than three years. During that time he became one of Oregon’s best-known celebrities and a major attraction at the Oregon Coast Aquarium in Newport.

For centuries orcas were assumed to be savage predators, roving wolf packs of the sea, attacking seals, sea lions, and other whales many times their size. In the early 1960s it was discovered that orcas could adapt to captivity. They were able to form relationships with human trainers and learn spectacular tricks. A huge orca leaping from the water became a feature of aquarium shows.

An orca’s ability to sell tickets made up for the difficulty of capturing the animals and the expense of providing a habitat where they could survive. The demand for orcas led to the decimation of pods in the North Pacific, causing growing concern about the advisability of the entire enterprise.

The orca who became known as Keiko was captured in Iceland in 1979. He was exhibited there for three years, then sold to Marineland in Ontario, where he began performing for audiences. Although Keiko appeared to enjoy contact with humans, his dorsal fin began to droop. He also developed skin lesions.

In 1985 Keiko was sold to Reino Aventura, an amusement park in Mexico City. Warmer temperatures and chlorinated water aggravated the lesions and Keiko’s deteriorating health. Keiko would most likely have died within a few years under these conditions.

However, in 1993, Warner Brothers released Free Willy, a film about a boy who frees an orca from an unscrupulous amusement owner by returning him to the sea. Keiko starred as the orca. The success of Free Willy and its sequels posed a moral dilemma for the studio, the filmmakers, and its audiences. How could they cheer Willy’s final leap to freedom knowing that Keiko, the real orca, was living under less-than-adequate conditions?

Warner Brothers and Craig McCaw, a Northwest cellular communications entrepreneur, established the Free Willy Keiko Foundation in 1995. Donations large and small funded the building of a special facility for Keiko at the Oregon Coast Aquarium in Newport. With the help of the United States Air Force and UPS, Keiko arrived at his new home in Oregon on January 7, 1996.

Keiko thrived in his new environment. He gained weight and his general health appeared to improve. He also became a major attraction at the aquarium. This posed a second dilemma. Keiko was ultimately supposed to be released into the wild. His stay in Oregon could only be temporary, until his health improved enough for him to be released into the wild.

Many marine biologists felt this was unrealistic. Having depended on humans for so many years, they doubted Keiko could learn to survive on his own.

Nonetheless, on September 9, 1998, Keiko left Oregon. He was flown to a sheltered bay in Iceland when Jean-Michel Cousteau’s Ocean Futures Society took over his care. Part of his training included swimming in the ocean outside the bay.

Keiko disappeared on one of these excursions. He eventually turned up 870 miles away off the Norwegian coast. Again, he became an attraction as boatloads of sightseers came out to see him. Keiko appeared to enjoy the attention. He accepted food from the visitors and even allowed some to climb on his back, defeating the whole purpose of bringing him from Oregon.

Keiko’s handlers eventually herded him to Taknes Bay, hoping he might join a passing orca pod. These hopes never materialized. Keiko remained in Taknes Bay as his health deteriorated. On the morning of December 12, 2003, Keiko beached himself. He died of pneumonia.

The Oregon Coast Aquarium held a memorial service for Keiko on February 20, 2004. Seven hundred people attended. Keiko was never replaced. Oregonians are no longer comfortable with the idea of turning orcas into tourist attractions.

One positive outcome of Keiko’s story is that it became an early step in changing public attitudes in the United States and worldwide towards the morality of capturing orcas for exhibition in public and private aquariums. Keiko’s experience convinced large numbers of people that while orcas might adapt to captivity in some ways, they could not thrive in such limited environments. Unlike the story of the orca in the film Free Willy, Keiko’s experience proved that even with the best intentions and the guidance and support of marine biologists, it was extremely difficult to return a captive orca to the wild.

The final shock to the idea of captive orcas as happy, gentle giants occurred at Orlando, Florida’s Sea World in 2010 when a trainer, Dawn Brancheau, was killed by one of the animals she worked with. Gabriella Cowperthwaite’s documentary film Blackfish, premiering at the Sundance Film Festival in 2013, focused on that orca, Tillikum, who had also been involved in two other fatalities besides Ms. Brancheau’s. Blackfish documents how a highly intelligent and active animal, used to swimming 100 miles or more a day, deteriorates physically and mentally in the limited concrete pool of an aquarium. It is the equivalent of locking human beings in a clothes closet and keeping them there for decades. The film sparked a public reaction against Sea World. As a result, the company ended its performing and breeding programs in all its aquariums.

Keiko lived in Oregon for fewer than three years. Even so, Oregonians still think of him as one of their own. Although his story did not have the happy ending of Free Willy, it changed attitudes toward “animal attractions.” Increased legislation world-wide protects orca pods as endangered species. Only one orca has been taken captive in North American waters since 1976.

-

![Jump-Off Joe, Newport, 1913.]()

Newport, Jump Off Joe, 1913.

Jump-Off Joe, Newport, 1913. Photo A.L. Thomas, Oreg. State Univ. Archives, N 174-X

-

![]()

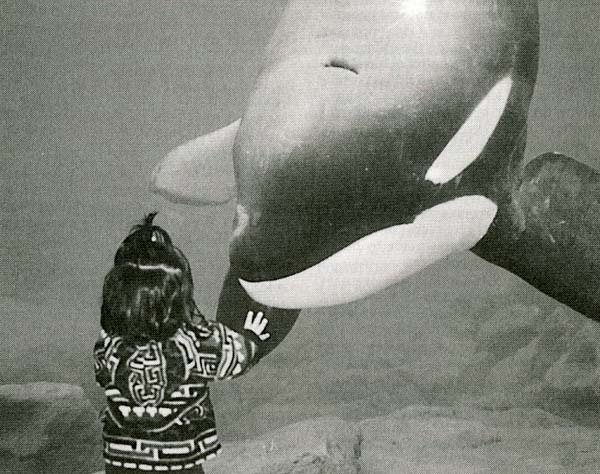

Keiko at the Oregon Coast Aquarium, 1996.

Courtesy State of Oregon, Oregon Blue Book

Related Entries

-

![Columbia Slough Orca (1931)]()

Columbia Slough Orca (1931)

In the early morning hours of October 12, 1931, a large creature was sp…

-

![Hatfield Marine Science Center and Visitor Center]()

Hatfield Marine Science Center and Visitor Center

The Hatfield Marine Science Center (HMSC) on Yaquina Bay in Newport was…

-

![Newport]()

Newport

Newport, with a population of about 10,256, is the largest city in Linc…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Preston, Julia. “Willy is Freed! Well, Moved, Anyway.” New York Times, Jan. 8, 1996.

“Wildlife; Free Willy: The Denouement.” New York Times, Sept. 6, 1998.

Muldoon, Katy. "The back story on Keiko and trainer Stephen Claussen, who died in a New Jersey plane crash." Oregonian, May 20, 2008. https://www.oregonlive.com/oregonianextra/2008/05/the_background_on_keiko_and_tr.html

"Keiko the killer whale dies." Associated Press, December 13, 2003. http://www.nbcnews.com/id/3700297/ns/world_news/t/keiko-killer-whale-dies/#.XXaOCi5KhaQ

Blackfish (film). http://blackfishmovie.com