Hall Jackson Kelley of Massachusetts was a tireless promoter of the American colonization of Oregon. His effort to lead New Englanders to establish a colony in Oregon in the 1830s was a failure, but historian Frances Fuller Victor nonetheless wrote that Kelley deserved to be considered “one of the fathers of Oregon.” Today’s historians are less willing to go that far. Kelley may have been “the most persistent” of early promoters of Oregon, historian William Robbins writes, but also, “some would say, the most unmoored from reality.”

Kelley was born in Northwood, New Hampshire, in 1790. After graduating from Middlebury College in 1813, he took a position as a schoolteacher in 1818. He taught in several grammar schools in Boston until 1823, when he was terminated from his teaching position for unknown reasons. During those years, he was twice married and fathered four sons. In 1823, he moved with his second wife to Charleston, Massachusetts, where he made a living as a surveyor and published several elementary school textbooks. In 1828, he invested in a textile mill planned for the village of Three Rivers, a plan that resulted in his bankruptcy and financial ruin.

It was in 1817, as Kelley was beginning his teaching career, that he had a life-changing experience, sparking ideas that would obsess him for three decades. The first edition of the journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition had been published a few years earlier, and Kelley read them avidly. Toward the end of his life, he described his response this way, referring to himself in the third person: “He then conceived the plan of [Oregon] colonization, and the founding of a new republic of civil and religious freedom on the shores of the Pacific Ocean…and in despite of [sic] entreaties of prudent, worldly-wise friends, he resolved on the devotion of his life in the realization of his plans.” He also aspired, he wrote, “to promote the propagation of Christianity in the dark and cruel places about the shores of the Pacific.”

Kelley had collected enough information about Oregon by 1828 that he believed he was ready to implement his colonization plan. He enlisted a Massachusetts congressman to introduce the first of many petitions and memorials in Congress requesting federal aid to establish a colony in Oregon. In 1829, he established the American Society for Encouragement and Settlement of the Oregon Territory, publishing promotional pamphlets and making speeches to recruit colonists for his effort. Typical of the overwrought rhetoric of his writings was his claim that Oregon was “the most valuable of all the unoccupied parts of the earth.” In one of Kelley’s pamphlets, according to Robbins, he “plagiariz[ed] from earlier journals and us[ed] his imagination to fill in the gaps.”

In 1832, Kelley dubiously claimed to have recruited four or five hundred colonists for Oregon, but his ability to organize a planned departure ended in failure. In the spring of that year, Nathaniel Wyeth and four other Kelley recruits set off for Oregon without him. Wyeth returned in 1834 and led an overland expedition, including naturalists Thomas Nuttall and John Kirk Towsend and Jason Lee and his nephew Daniel, to the lower Columbia.

Having failed in his colonization effort, Kelley ventured to Oregon on his own in March 1833, traveling by land and riverboat to New Orleans and then to Veracruz, Mexico. After a perilous overland journey to Mexico City and then to La Paz in Baja California, Kelley reached San Diego in April 1834, where he met trapper Ewing Young. They devised a plan to purchase horses and mules to sell in Oregon. On the way, Kelley contracted a near-fatal case of malaria. Hudson’s Bay Company trapper Michel La Framboise encountered Kelley in southern Oregon, nursed him back to health, and got him to Fort Vancouver by October.

When Young arrived with the herd, he discovered that Chief Factor John McLoughlin had received a letter from the governor of California reporting that the horses had been stolen. Young was able to clear himself and Kelley of the accusation, but Kelley was forced to live in a small shack outside the fort because of his lingering illness. Contributing to Kelley’s ostracism was the fact that his advocacy for Oregon colonization was well-known to HBC and was considered a threat to their interests.

In 1836, whether out of sympathy or just to rid himself of Kelley’s presence, McLoughlin provided him with passage to Hawaii and enough funds to get him to Boston. By then, Kelley was a broken man, estranged from his family and without means to support himself. Nevertheless, he continued to publish articles in local newspapers from his home in Three Rivers and to pester Congress with memorials and petitions, the last in 1866. In 1868, he published A History of the Settlement of Oregon and the Interior of Upper California, a self-serving account of his life’s work. He died, blind and penniless, on January 20, 1874.

Kelley’s name appears among the names of important historical figures at the Oregon State Capitol. In 1926, Kelley Point at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers—the planned location of Kelley’s aspirational American city—was named for him. One can discount the impact of his many articles and publications on Oregon resettlement, and his memorials and petitions to Congress probably had little influence. But his writings had some effect in promoting Oregon resettlement, and he deserves credit for helping inspire Nathaniel Wyeth and Ewing Young to travel to Oregon, where they made important contributions.

-

![]()

Hall Jackson Kelley.

Courtesy Library of Congress

-

![]()

Kelley's Map of Upper California and Oregon, 1839.

Oregon Historical Society 18.2 (March 1917)

-

![]()

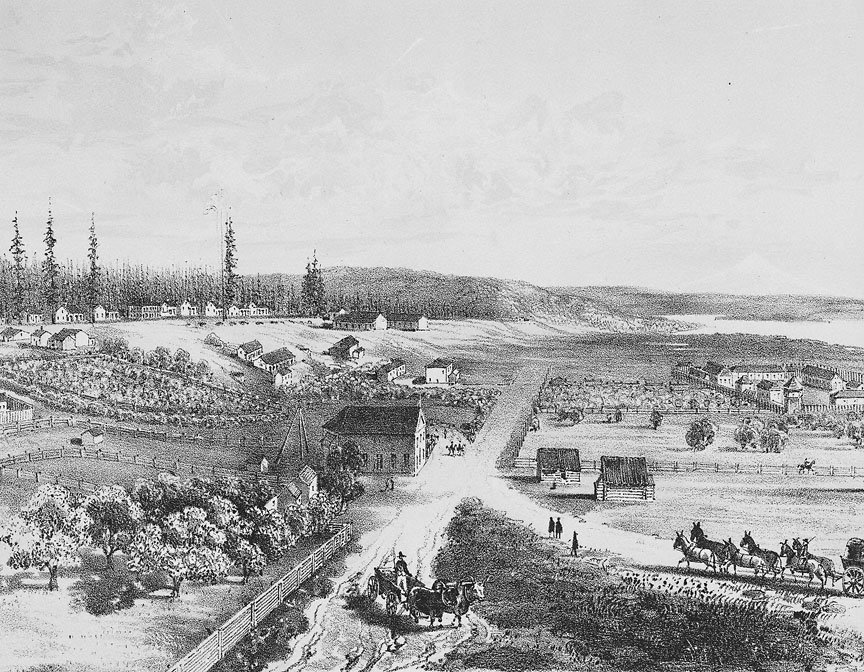

Kelley's plan for a trading town at mouth of Willamette River.

Oregon Historical Society 18.1 (March 1917)

Related Entries

-

![Ewing Young (c. 1796–1841)]()

Ewing Young (c. 1796–1841)

Ewing Young was a Santa Fe trader, a Rocky Mountain man, a California l…

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

-

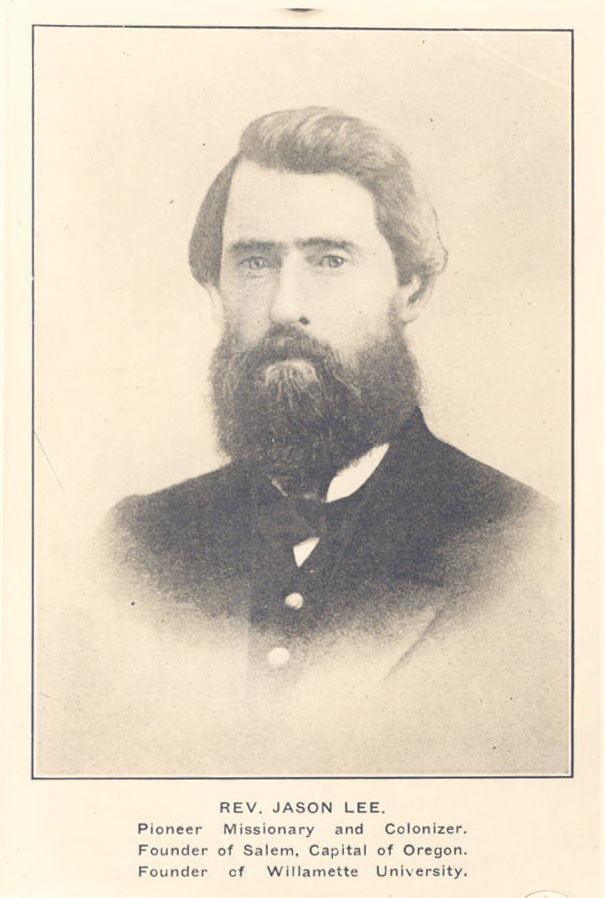

![Jason Lee (1803-1845)]()

Jason Lee (1803-1845)

Few names in the history of early nineteenth-century Oregon are better …

-

![Thomas Nuttall (1786-1859)]()

Thomas Nuttall (1786-1859)

Thomas Nuttall was one of the most enthusiastic and energetic of the ea…

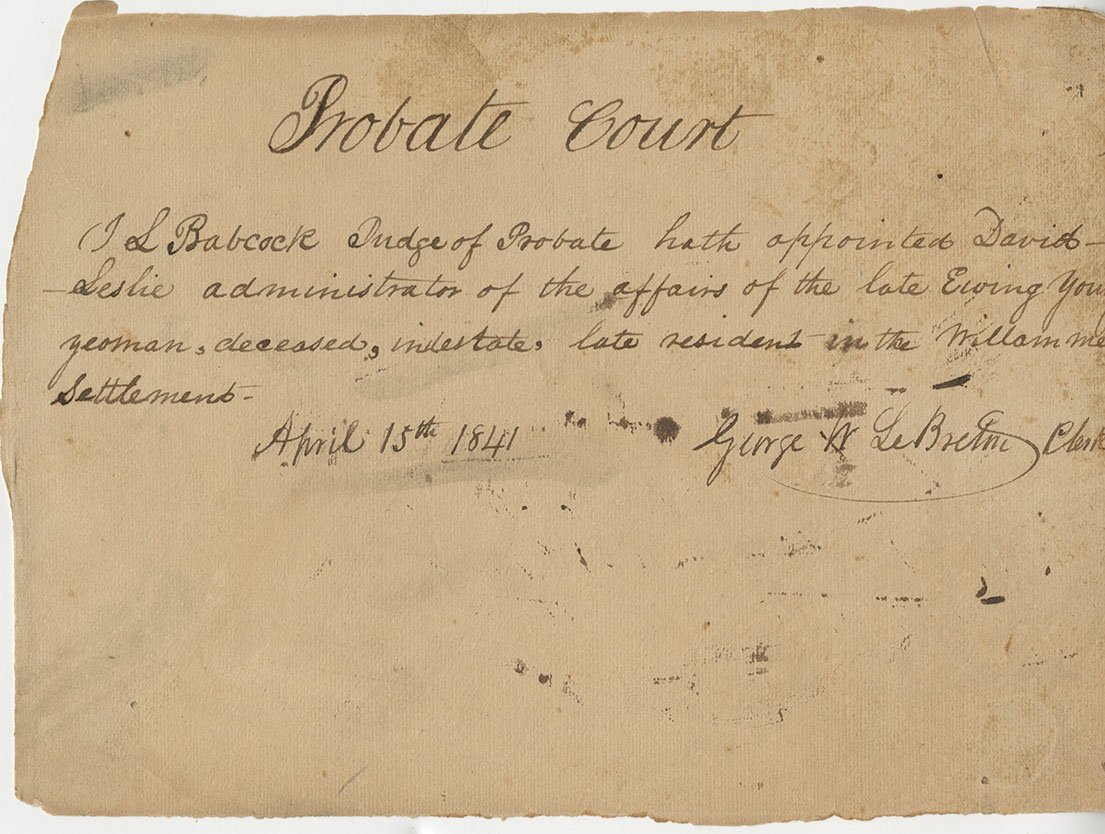

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Victor, Francis Fuller. “Hall J. Kelley, One of the Fathers of Oregon.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 2.4 (1901): 381-400.

Robbins, William G. “Willamette Eden: the Ambiguous Legacy.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 99.2 (1998): 196.

Powell, Fred Wilbur. “Hall Jackson Kelley—Prophet of Oregon.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 18.1 (1917): 1-10.